This article marks Brazilian Black Awareness Month 2025 and is part of RioOnWatch‘s series on Memories of Favela Power, which documents and celebrates the history of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas through narratives and reports from residents’ collective memory, in their daily struggle to lead fulfilling lives.

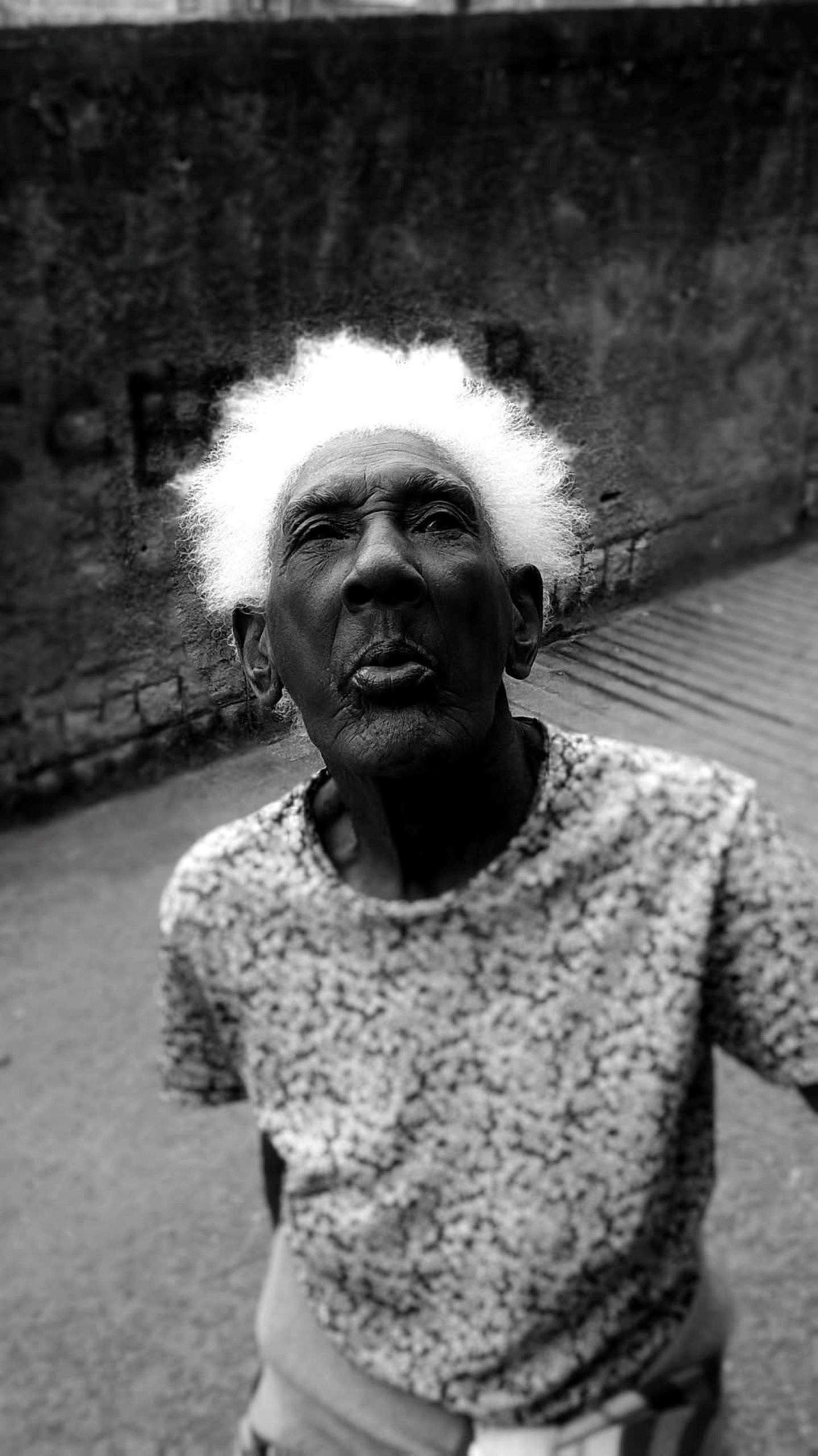

Almost every day, you were sure to find Dona Pascoalina—as Pascoalina Oliveira da Silva was known—sitting on a chair outside her home, enjoying the sun. That’s what she loved to do, watching the comings and goings of neighbors outside her door on Rua Nova, one of the areas of Morro do Borel, a favela in Tijuca, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone.

Everyone who passed by made a point of greeting her. After retiring, her pastime was to take a roll of tobacco from her pocket and light her pipe. “A little drink, smoking a pipe and eating healthy food.” According to the community matriarch, that was the secret to her longevity. She passed away of natural causes at the age of 88 in November 2019. However, her exact age is unknown, as she had two birth records with different dates. Even her family isn’t entirely sure.

Her pipe was replaced several times over the years. According to Dona Pascoalina, “It hasn’t been long [since the last one]. It cracks on one side, cracks on the other. So I cut it like this to remove any little thing inside. Then I lie in bed and a little smoke comes out. Sometimes it won’t light, and I curse it—but I always have it with me.”

In an interview conducted in July 2019, the final year of her life, she shared a bit of her story as a Black woman who left her family in the countryside to come to Rio de Janeiro in search of work and a better life. Born in the interior of Minas Gerais, Pascoal—as she was widely known—began working at the age of five, helping her parents on a landowner’s farm. Her family is also unsure as to what city Pascoalina was born in.

“I used to tend the plants… Then I would just stay there doing farm chores, taking care of the chickens, taking care of the pigs. I worked with a hoe too. I was very small, only five years old. It was a lot of work, and we lived in a house and had to walk everywhere, because there was nothing—no car. The landowner would give us a little something too: a portion of rice, a portion of beans, a portion of flour.” — Pascoalina Oliveira da Silva

When she decided to come to the state capital of Rio de Janeiro, she left behind three siblings and arrived at the age of eleven by train with an aunt. “I came on a Maria Fumaça [as steam locomotives were popularly known in Brazil],” she recalled. Once she arrived, she lived in Penha, where she worked for the first time.

After some time settled in Rio, Pascoalina built a small house in Morro do Salgueiro, another favela in the North Zone. By then, already a devoted follower of samba and its religious expressions, she joined the baianas section—a traditional, mandatory segment of every carnival samba school that represents samba’s Afro-Brazilian roots—of the Salgueiro samba school.

“I got together with this old man, the father of one of these kids [the late father of some of her children, whose name she couldn’t remember], and I stayed with him [for a while]… When I left Salgueiro, I came here with another guy. Then [after some time], I left the other guy [the man from Salgueiro]—he was useless, a womanizer… I was also quite the flirt. Honestly, I really enjoyed my life: I used to go to balls to dance.” — Pascoalina Oliveira da Silva

Pascoalina was raised by her cousin and godmother. At 19, she moved to Morro do Borel, began her studies and reached the fourth grade. She witnessed all the changes the favela went through: from muddy streets and plasterboard houses to brickwork and paved roads. “When I arrived, all of this was [built with] plasterboard,” she said. “It was all mud. I don’t really have a sense of how things were before… but this house here, the boss helped me build it,” she recalled, referring to her former employer at a household where she once worked.

In Rio, she spent most of her life employed as a domestic worker in different homes. “I worked in a house in Copacabana. I also worked on Conde de Bonfim Street over there [in the lower part of Tijuca], and in a square downtown. I worked for rich ladies,” said Borel’s treasure.

Borel’s Healer and Midwife

Considered almost immortal, Pascoalina remained mysterious: she had two ages. Although she would proudly claim one, her family insists she was older. Her daughter, Maria Antônia de Oliveira Soares, 65, reveals that her mother was slightly older than she claimed, because she had her documents issued twice. According to Soares, “At the registry office, the clerk gave her a new date [of birth].” The truth is, age was just a detail in the life of a woman who overflowed with youthfulness and a zest for life.

Pascoal recalled the time when she worked as a midwife and healer in the favela, including the moment she delivered her own grandson, Victor, at home—which was common practice. “It was my mother who delivered Victor,” says Soares.

Ancestral knowledge also showed through in the spirituality she carried within her, taking on midwifery as a legacy from Dona Zazinha, an older woman who lived in a neighboring yard and performed her healing prayers and deliveries back when there weren’t many houses around. “She was the one who delivered my children at home,” said the matriarch.

Many times, residents would come to Pascoalina’s house seeking help. Inside, a special space was dedicated to the saint she prayed to for protection and health, with Our Lady of Aparecida occupying the most prominent spot on the altar. “I make my prayers every day, don’t I, my little saint? There’s another little saint here too, for whom I pray for the children.”

Although her daughter emphasized that she was more connected to the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé, when asked about her spiritual practices, Dona Pascoalina said she was Catholic. “I’m Catholic: Roman Catholic.” However, like many Brazilians, she also drew on Afro-Brazilian religious traditions to heal and protect her loved ones. “I’ve prayed [with the intent to heal and bless] for some children. We also incorporated [Candomblé] into our practice.”

Ana Paula Rodrigues, 45, born and raised in the community, remembers the legacy of Borel’s healer. She says that two of her daughters received Pascoalina’s prayers and blessings. Rodrigues was always Pascoalina’s neighbor, living just two houses away.

“She prayed [healing and blessing] for all the children. She prayed for Marceli, she prayed for Milena. As a midwife, I remember stories about her delivering many babies. And as a healer, we would go to her so she could pray for the children. [She used to bless kids against] the evil eye—it used to be [a] very common [belief] back then.” — Ana Paula Rodrigues

Her daughter highlighted just how important Pascoalina was to the Borel community.

“My mother was one of those rare, invaluable people—not just for me, but for most people in Borel. She delivered many babies and offered many prayers for the community.”— Maria Antônia de Oliveira Soares

The Many Changes She Witnessed in the Favela

Over the years, the favelas’ struggles for dignity and respect also became part of Pascoalina’s memory. She recounted several conflicts with the police. Pascoalina remembered that, in the past, her children were regularly assaulted and taken away by the police.

“Up came the police: ‘Come here.’ They’d grab my son, take him up and down and beat him up. Then they’d take him to the [police] station. I spent a lot of time there too [at the station] looking for them… You’d go down the hill and all you saw were the bodies stretched out on the ground… Everything has changed, the favela has changed. There aren’t deaths [like before]; you’d go out and see all those bodies on the ground. It’s not like that anymore. Every once in a while, the [police] helicopter shows up and fires a shot, like last Wednesday.” — Pascoalina Oliveira da Silva

Within this reality, she had one fear: dying by gunshot. “Death may come when it wants, but not by gunfire.”

By this point, her prayers had become less frequent because Pascoalina had injured her knee. “After I got sick, I lost my strength, my energy, my drive. I can’t even keep my balance anymore,” she said, emphasizing her condition.

Her hair turned completely white, she said, from thinking so much about life. “It makes my blood boil just thinking about life. I think about life, I think about my children, I think about my granddaughters. And then my hair turned white really quickly.”

Pascoalina Oliveira da Silva passed away on November 17, 2019. She left behind five of her 16 children. She knew 16 grandchildren, 38 great-grandchildren, and six great-great-grandchildren. Her legacy and contribution to the history and identity of Morro do Borel are far greater than her passing, and they continue to be felt in the community even six years after her death.

*Some information, such as her place of birth and exact age, could not be confirmed, as Pascoalina Oliveira da Silva’s documents were in the possession of one of her daughters, who passed away in 2024.

About the author: Igor Soares was born and raised in Morro do Borel and has a journalism degree from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). He currently contributes to #Colabora and works as a freelancer. He has experience covering topics related to cities, human rights, and public security, having previously worked at Estadão, Portal iG, and produced reports for Folha de São Paulo.