It is a chorus heard from favela activists across the city, louder in these recent weeks of protest, but it still rings with a special weight coming from the Vila Autódromo Residents’ Association, having gained international recognition for its creative and committed battle against eviction: “We built our community. We have the right to be here. We will stay!”

Vila Autódromo residents and allies organized a march from the community through the surrounding area on Saturday July 20th to express solidarity for the community’s land battle and that of all favelas who struggle for their constitutional housing rights, as well as to voice disapproval of the militarization of favelas by state police forces. Organizers planned the march to demonstrate continued community opposition to the threat of eviction. Given the community’s strong legal rights, the Mayor has repeatedly claimed that the majority of residents want to leave (70% according to him at a recent gathering) when the Neighborhood Association and State NUTH (housing public defenders office) have registered the exact opposite.

Vila Autódromo residents were emboldened during Saturday’s protest due to conflicts over the previous weeks, including representatives of the City arriving to try and persuade residents to sign up for homes in a public housing project being built one kilometer away. These contractors of the Municipal Housing Secretariat (SMH), led by a woman named Marli Peçanha, had entered Vila Autódromo previously in March, going door-to-door and pressuring residents to sign up for resettlement housing. In addition to residents holding individual land titles, the community as a whole has a 99-year concession of use agreement for their land, which means the only way the city can accomplish their removal–something that has been a goal of various legislators using various justifications since 1992–is if residents agree on their own free will to take payouts or units in a public housing complex. Under Brazilian law, fair compensation must be given in the case of resettlement. Colorful brochures and even a bus tour have been offered to Vila Autódromo residents to convince them of the quality of life in the new Parque Carioca development, but many residents are unhappy with the small size of individual units and what’s seen as a development style that contradicts their needs, and are skeptical of the quality of its buildings due to issues such as flooding and cracks in other housing projects finished by the city in the last three years.

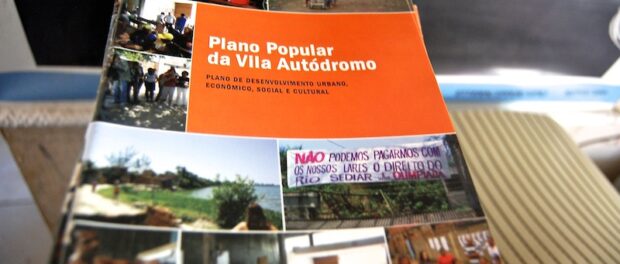

In 2012, Vila Autódromo worked with city planning students and professors from Rio’s two federal universities, UFRJ and UFF, to create an upgrading plan that would cost a fraction of and include higher-quality homes than the relocation proposal, and the majority of residents in the community support the plan. The plan was delivered to Mayor Eduardo Paes in August, and the Mayor promised a reply in 40 days. To this date no reply has been given. Instead, the city’s latest strategy has been to approach unsure residents or those who don’t fully understand their rights to try and persuade them, making them feel relocation is inevitable and wearing them down.

Last month, the week of June 24, city representatives tried an additional tactic: five homes spread out throughout the community were marked for removal. Scattered removals have become a well-known strategy to weaken resistance over the past few years, whereby the presence of debris in demolished homes attract a host of issues, making life unbearable for those who remain, while sending a strong message that their eviction is imminent. As such, Vila Autódromo leaders contacted the Public Defender’s Office immediately, who then notified City authorities of residents’ concession of use and a court order prohibiting demolition of any homes.

Visits from City Contractors

On the morning of June 28, over the course of several hours, four different people tried to enter Vila Autódromo claiming they were coming to visit friends in the community. Residents, suspicious these visits were disguised attempts by City authorities to conduct removals or intimidate neighbors to sign relocation agreements, created a human barrier at the entrance of the community. They also asked these unidentified visitors to call their friends in the community to its entrance to meet them. When no one came from inside, they were asked to leave.

Around noon, two of the visitors returned with Peçanha, three other housing authority representatives, and four military police, one of whom carried a highly visible rifle.

Peçanha pushed through the crowd saying with a raised voice that she had come to talk to residents. “We are all right here,” said Altair Guimarães, president of the Vila Autódromo Residents’ Association. “We can all talk here, without force. What would you like to say?”

Peçanha and Guimarães engaged in over half an hour of intense conversation with residents, police, city employees, and journalists gathered around. More than once, Peçanha asked that Guimarães speak to her away from the crowd. Guimarães read from the notice issued by the Public Defender’s Office, and the dozens of residents gathered broke into cheers of “go away, City Hall!”

Guimarães told Peçanha and her colleagues that they had no right to enter the community with force and through deceptive tactics, and if she wanted to address residents, she could do so at the community entrance. He acknowledged that it was each resident’s individual choice whether they wanted to stay in Vila Autódromo, but for the majority of residents who did want to stay, he would not accept intimidation.

After forty minutes, the city officials committed to scheduling a meeting with a small group of Vila Autódromo representatives outside the community and drove away with the two police cars tailing them. Residents cheered.

Demonstrating

In the following weeks, the meeting with city officials was delayed, and then cancelled, and Residents Association member Inalva Mendes Brito attended organizing meetings of different social movements in the city to speak about why it was important to have a protest in Vila Autódromo at this particular moment. “This is a decades-long battle,” she said, “Vila Autódromo has mobilized its networks and its allies to defeat City Hall’s latest advance, and serves a symbolic role in the city’s conversation about favela removals.” She invited all to Saturday’s march.

Saturday afternoon around 2pm, over five hundred people gathered in Vila Autódromo to hear speeches from residents. They then departed down Avenida Embaixador Abelardo Bueno with a sound car and a growing number of police ahead and behind, passing signs for the future Olympic Park and waving banners representing the National Movement for the Right to Housing, the Pastoral das Favelas, Favela Não Se Cala, and the community of Horto. Residents Association member Inalva wore the red pointed hat of the mascot of the Removals Cup, a resistance event organized by the Popular Committee of the World Cup and Olympics. The Saturday protest was covered live by Mídia Ninja.

Some of the most powerful banners were those made by Vila Autódromo residents that morning, such as “My House, My Life [the name of Brazil’s federal public housing program] Was The One That I Built” and a banner listing the community’s different advances in their journey to remain over the years.

After over a kilometer, the march doubled back and passed Vila Autódromo to turn right and slightly north into Curicica as dusk and then nighttime fell. When the group passed the favela of Asa Branca on the right and several neighboring Curicica favelas on the left, Asa Branca Residents Association president Carlos Alberto Bezerra da Costa spoke into the microphone of the soundcar in support of Vila Autódromo: “The threat of removal is something that could happen to all of us,” he said. Asa Branca residents streamed out of their homes to watch the procession.

The next stop was the Globo TV Production Center, also in the area, where protesters unfurled their banners in front of guards at the entrance and gave a series of speeches about the role of Rio’s mainstream media in supporting the state’s desire to remove favelas and criminalize their residents. “The same media that supported Brazil’s dictatorship is suppressing our narrative now,” said Guimarães.

Vila Autódromo resident Maria Jesus Evanilde, 41, participated in the protest with her daughter, who emphatically carried a sign and gave a speech in front of Globo. Evanilde said she originally considered the idea of moving to public housing, but the more she learned about it and understood the community’s unification efforts, the more she preferred to stay where she was. “I am determined now to keep living in Vila Autódromo.”

The march ended in front of the proposed housing project itself: Parque Carioca. “We don’t want this,” protestors chanted as they spread their signs across the front fence of the construction site. After cheers, group photos, and participants trailing off into the night, one sign remained taped to the oversized photo of a smiling family promoting the public housing project: “No to removals. We want investment in housing rights, health, and education.”

!["We're afraid of suffering, not losing. Those with faith in God reach [their goals]"](https://www.rioonwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/DSC_0018-620x264.jpg)