Favela removals and home demolitions have become controversial elements of urban investment in Rio de Janeiro leading up to the World Cup 2014 and 2016 Olympic Games. Activists in several favelas have spoken out about the lack of dialogue and consequences of losing homes during upgrading. In the latest 2013-2016 Strategic Plan of the City announced during his campaign for reelection, Rio’s Mayor Eduardo Paes called for both a 5% reduction of favelas and the elimination of residences in environmentally protected areas and risk areas. This agenda disproportionately affects favelas.

Now that foreign investment and tourists are flooding Rio, there is the risk of heaping further injustice upon Rio’s hardest working residents by displacing them from their homes. In many cases, evictions result in residents losing the labor and capital they have invested in their residences, adding to the community fragmentation and distress experienced by displacement. Home ownership is highly valued in Brazilian culture, especially among lower income groups. In upgrading meetings I attended in Santa Marta, favela residents stressed that their homes are part of their identities and that government housing projects have proven to have shoddy construction. Unsurprisingly, the long-time residents of favelas that are faced with removal or resettlement have organized against evictions and taken their fight to the courts.

While favela residents are struggling to secure housing in the urban center near their livelihoods, Rio’s wealthy seek seclusion and privacy for their homes. Wealthy squatters have constructed mansions in the isolated beaches and islands in the national park a few hours south of Rio near Paraty. Brazil’s rich use political connections to fight for their right of possession and are defended by Rio’s best lawyers. From the heights of the favela Santa Marta, where families that have lived there for three generations are threatened with eviction, luxury homes in precarious locations are visible in the heights of Laranjeiras and Humaitá. At the same time that ranchers in the Brazilian Amazon are asserting their right to possession in the legislative battle over the Forest Code, urbanization is dispossessing thousands of families in the state of Rio. Ostensibly, the goal of upgrading is to integrate favelas into Rio’s urban life, but the current process of removal is displacing historic injustices rather than correcting them.

My research findings indicate that recent favela upgrading programs in Rio use unprecedented levels of environmental framing of urban policy for favelas. Rio’s government has redefined the limits of human settlement in Rio by mapping geological risk assessments onto favelas in or near environmentally protected areas. This has been done in the name of both protecting the environment and human life. But there have been a number of contested recent cases where independent engineers and technical experts called to communities reach assessments that run counter to GeoRio claims or insist on the economical solution of slope stabilization.

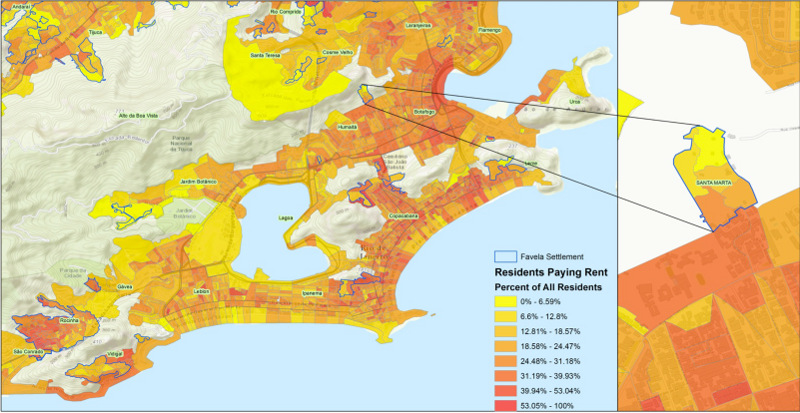

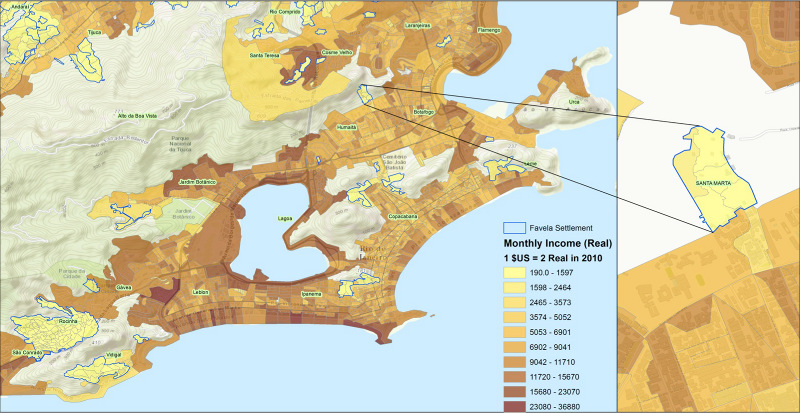

The social consequences of this framing are considerable. Residents of Rio’s favelas in the South Zone have a higher level of home ownership than in the rest of Rio, except in Rocinha where renting dominates. They also have lower incomes per household than most of Rio, meaning that their life savings resides in their homes. The stakes are made higher even because often livelihoods are rooted to their homes.

In the first phase of favela removals, such as in the favela Metrô-Mangueira starting in 2010, evictions were abrupt and in some cases coercive. After being presented with a take it or leave it offer, holdouts were cut off from state services and left to suffer in the demolished ruins of their neighbors’ homes. This exposed residents to increased risk of diseases like dengue and harkened back to the decades of neglect suffered by favela residents from lack of services in their communities. It also demonstrated that the Rio city government was willing to use public service cuts as a tool to coerce favela residents to abandon their homes. Infrastructure denial has often been used for favela control in Rio before and after evictions since the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) occupations began in 2008.

The United Nations criticized these evictions on human rights grounds in 2010, causing Rio’s government to moderate their approach somewhat. The continued forced removals in the periphery of Rio have come to the attention of Amnesty International, which is currently monitoring favela removals and resettlement. The UN has the right to housing included in its charter, and that has also been legislated in Brazil. Since 2001, Brazil’s federal government has implemented strong protections for the rights of urban informality and this external criticism calls into question the implementation of the federal City Statute in Rio. The current phase of favela displacements involves more sophisticated public relations and technocratic assessments, as favelas are remapped within the ominous sounding ‘area of risk’ classification for the favela upgrading process in Rio.

Area of risk is a phrase that conveniently stifles argument and is ambiguous at the same time. On the ground in the Rio metropolitan area, this designation joins the concepts of environmentally protected zones with the prevention of ‘natural’ disasters. The areas at the top of hills and on inclined slopes are special priorities under this policy; the city argues these areas need to be reforested to reduce the risk of disasters triggered by high levels of rainfall. The primary criteria for designating risk on urban land are human occupation and inclined terrain, according to GeoRio, Rio’s municipal geologic evaluation agency. Anyone that visits Rio can see that much of the city is constructed on inclines and underneath large escarpments of rock.

The area of risk designation, as a legal tool, links a policy of favela contraction to a policy of conservation and reforestation, all hot button issues for environmentalists in Brazil and international NGOs. This framing of the issue dulls international criticism of the removals and delegitimizes popular activism by favela residents (how can you be against protecting lives and the environment?). Rio favelas that were partially mapped within these environmentally protected zones have been reassessed for risk by municipal experts since the outset of the UPP project. Previous ‘definitive’ assessments were cast aside as new versions were produced with new technologies and governmental priorities. Favela residences that are mapped within high risk areas are subject to removal or resettlement programs. Despite the promulgation of strong constitutional protections for informal settlements in Brazil, the area of risk clause in federal legislation, i.e. the Forest Code and Ministry of Cities, is the primary legal tool being used to displace residents in the historically established favelas of Rio, many of which were legalized as zones for upgrading after 2000. Where residents will live after the removals is a secondary concern for the City government, creating another level of insecurity for vulnerable citizens of Rio.

In fairness, the risk of landslides in Rio de Janeiro state has a history. The 2010 mudslides in Niterói and Novo Friburgo that resulted in the loss of thousands of lives heightened the political pressure for favela resettlement in areas of risk. But to take that emergency as the starting point for resettlement policy ignores a history of neglect in service provision and failed urban planning. For decades, favela residents were left to their own devices when it came to affordable housing, sewerage, sanitation, and available land. Rafael Gonçalves, a professor at PUC-Rio, recently argued in his book that Rio’s administrators used the law to maintain the presence of favelas as cheap sources of labor for industry. The selective implementation of Brazilian law made it possible to both tacitly allow favela settlements and deny public services to ‘precarious’ settlements. This policy vacillation set the stage for the disasters of 2010, despite previous efforts to integrate Rio’s favelas carried out during the Favela-Bairro upgrading projects.

In the current wave of favela resettlement, Rio’s government has opted to concentrate most of its resources on the construction of public housing and removals, which in the short term is cheaper than upgrading the sewerage system in the ad hoc infrastructure of favelas like Santa Marta. If residents don’t agree to the resettlement options dictated to them, the amount offered for their homes is not enough to purchase a residence anywhere in the community from which they came, particularly in the upscale South Zone of Rio. With real estate speculation in the South Zone at a feverish pitch in the post-UPP era, purchasing a different home in central or south Rio, even in a favela, is cost prohibitive.

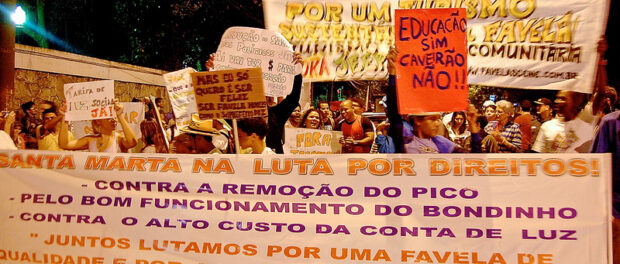

Similar to Babilônia, Chapéu Mangueira and Tabajaras–also located in post-UPP real estate speculation hotspots–Santa Marta is currently undergoing upgrading projects funded by the second round of public investment in Rio’s favelas under the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC). The promise of improvements for infrastructure and technical assistance for home construction under the PAC was welcomed when upgrading programs were launched, but the increased costs of utilities and loss of savings experienced by residents living in favelas has increased their financial insecurity rather than alleviated it.

Favela residents also must manage with precarious access to public services. In many cases, residents are paying for services that have not arrived, or are often offline, as in the case of water shortages and the bondinho (funicular tram) in Santa Marta. When these residents are displaced, they are not compensated for the labor and savings that have been invested in their homes. They are only compensated for the estimated value of the materials used for construction. Many residents prefer to move to another distant favela than face the cultural shock of adjusting to a distant housing project. One municipal employee working on favela integration in Rio told me that they expected residents would be removed to Campo Grande, which is more than two hours without traffic from the South Zone using public transportation. The implication was that if you can’t afford to live in the South Zone, you should move elsewhere.

Recent protests over the quality of public services and the priorities of the different levels of government in Rio show that it is not just favela residents that are feeling shortchanged by the planning strategies and aspirations of Rio’s politicians and ruling class. Last year, Rio’s Mayor Eduardo Paes said he wanted to be remembered as the Pereira Passos of this generation. Pereira Passos’ legacy in Rio was the destruction of tenement housing in the city center, reshaping Rio’s public spaces in the style of French modernist architects, and establishing Rio as a global tourist destination and playground for the rich. This is clearly happening again in Rio. The development plan for favelas, with its emphasis on cable cars and ecological aesthetics, demonstrates a priority on tourism in favelas rather than building infrastructure that would integrate favelas into the city.

The current agenda envisions further reducing the size and population of favelas as part the ‘ecological’ modernization of Rio. It is important to understand that this trend is defining who has the right to the city and who does not.

Charles Heck is a doctoral candidate in Human Geography from Florida International University in the department of Global and Sociocultural Studies. He lived in the Santa Marta favela during his field research and is currently writing his dissertation on upgrading and environmental discourse in Rio’s urban policy for favelas.