In 2003, President Luiz Ignacio “Lula” da Silva launched the Bolsa Família program to promote social progress for impoverished families. This and other programs were implemented in an effort to decrease Brazil’s infamously high inequality. At the time Brazil consistently occupied the first, second or third position as the world’s most unequal country. Incorporating what were previously four distinct programs under the umbrella of the Ministry of Social Development, this social program has become renowned as one of the most successful in reducing poverty rates not only in Brazil but worldwide. Bolsa Família’s wide appraisal led to its expansion in 2008, and today around 22 million families access its benefits. Today, Brazil occupies the position of seventeenth most unequal economy.

Bolsa Família, or “Family Grant,” provides a basic income subsidy to the poorest families nationwide. The program provides a direct income transfer, on a conditional basis, stimulating an immediate alleviation of poverty; while other conditions, like the stipulation that children must be enrolled in school and cannot miss more than 15% of their classes, fight long-term poverty. As a result it combats poverty while simultaneously promoting access to public services, like education and health.

How It Works

Participation in Bolsa Família is based on a family’s income. Those that qualify collect their specified amount of financial support on a Bolsa Família card. This card can only be used to withdraw that specified amount of cash at a certain bank, and will only be allocated to the head of the household, with preference given to the woman of the house (mother or grandmother). Each household’s benefits depend on the family’s size, the children’s ages, and the family’s overall income. As the policy seeks to stimulate the use of education and health services, benefits can be revoked if, for example, a child’s school attendance record fails to meet standards.

What Beneficiaries Say

Speaking with community leaders from three very different favelas across Rio de Janeiro, the overall reaction to the program was extremely positive. Yet while the program has beneficiaries praising its success, community leaders are more critical of its potential in alleviating long-term poverty.

Fogueteiro

Located in Santa Teresa in central Rio, Fogueteiro is a hillside community which had a violent history of drug trafficking before receiving the 15th Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in February 2011. The community started accepting benefits from Bolsa Família when the program was launched in 2003. Cíntia Luna, President of Fogueteiro’s Neighborhood Association, estimates that today around 70% of the community’s families obtain benefits: “If your income qualifies, it is easy to access. However if you are even just R$20-30 above the income bracket, you will not.” She complains that the strict system can either be impossible to access or as simple as registering, between two families with nearly identical monthly incomes. Although frustrated with that stringent divide, she applauds the program’s success in helping such a high percentage of the community. Cíntia also reflects on the policy’s main objective, that of combating poverty. Cíntia mentions some residents do abuse the program. In her opinion, a good number seek the Bolsa Família income as a replacement for employment, fostering a dependency on government support.

Located in Santa Teresa in central Rio, Fogueteiro is a hillside community which had a violent history of drug trafficking before receiving the 15th Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in February 2011. The community started accepting benefits from Bolsa Família when the program was launched in 2003. Cíntia Luna, President of Fogueteiro’s Neighborhood Association, estimates that today around 70% of the community’s families obtain benefits: “If your income qualifies, it is easy to access. However if you are even just R$20-30 above the income bracket, you will not.” She complains that the strict system can either be impossible to access or as simple as registering, between two families with nearly identical monthly incomes. Although frustrated with that stringent divide, she applauds the program’s success in helping such a high percentage of the community. Cíntia also reflects on the policy’s main objective, that of combating poverty. Cíntia mentions some residents do abuse the program. In her opinion, a good number seek the Bolsa Família income as a replacement for employment, fostering a dependency on government support.

Cíntia also recognizes the developmental benefits of Bolsa Família, praising the program’s emphasis on school attendance. School attendance has increased substantially in Fogueteiro. She finds the monetary motivation to educate the new generation somewhat unsettling, however: “Bolsa Família is a way for [the government] to force education. Some families have little interest in educating their children, so the government pays to stimulate that interest. Now [parents] have a reason to educate their children: money.”

Asa Branca

In Rio’s West Zone, Asa Branca has recently received municipal infrastructure investments and is a peaceful, low-lying community near the future Olympic Park. President of the Neighborhood Association, Carlos Alberto “Bezerra” Costa has only positive comments in regards to Bolsa Família.

In Rio’s West Zone, Asa Branca has recently received municipal infrastructure investments and is a peaceful, low-lying community near the future Olympic Park. President of the Neighborhood Association, Carlos Alberto “Bezerra” Costa has only positive comments in regards to Bolsa Família.

Immediately after the launch in 2003, those who qualified sought benefits, and today, Bezerra estimates that 80% of Asa Branca obtain benefits from the program. The remaining 20%, he affirms, either successfully improved their economic situations or never needed assistance in the first place. Bezerra also points out a huge increase in social mobility: he himself requested to stop receiving the monthly allowance, as he no longer needed the extra support. “There is not a sentiment of wanting to be unemployed here. We want to work. Bolsa Família helps keep us going when we are underemployed.” He continues, proudly emphasizing the effects the program has had on the younger generation: “The children attend school. We do not see children roaming the street during the day. The parents now have a reason to keep their child in school, so the children stay in school.”

Bezerra’s perspective reflects an overall view of Bolsa Família that is projected in both domestic and international press. According to a 2010 Economist article, “by common consent the conditional cash-transfer program has been a stunning success and is wildly popular… It is, in the words of a former World Bank president, a ‘model of effective social policy’ and has been exported around the world.” The program has indeed successfully reduced levels of poverty, as the number of impoverished families (monthly wage below R$800) has fallen more than 8% on a yearly basis since 2003. However, Pica Pau Neighborhood Association President, Irenaldo Honorio da Silva, offers a different perspective on Bolsa Família’s true impact.

Pica Pau

Pica Pau, a favela in Rio’s North Zone with significant infrastructure issues, has also been promised upgrading recently, under the municipal program Morar Carioca although this is currently stalled. Bolsa Família, on the other hand, introduced to the community around 2009 (after the 2008 expansion), has been quite steady in its support to the community. According to Irenaldo, “those who need financial assistance will receive it. If you need support but have not obtained Bolsa Família, it is probably due to a lack of documentation, or a child’s poor attendance records at school. It is the family’s problem, at least that is my opinion. If you want to receive Bolsa Família, you will.” However, according to Irenaldo, only 40% of Pica-Pau’s families receive Bolsa Família. This could be due to various factors; among them the relative newness of the program and thus lack of awareness, or low levels of school attendance.

Pica Pau, a favela in Rio’s North Zone with significant infrastructure issues, has also been promised upgrading recently, under the municipal program Morar Carioca although this is currently stalled. Bolsa Família, on the other hand, introduced to the community around 2009 (after the 2008 expansion), has been quite steady in its support to the community. According to Irenaldo, “those who need financial assistance will receive it. If you need support but have not obtained Bolsa Família, it is probably due to a lack of documentation, or a child’s poor attendance records at school. It is the family’s problem, at least that is my opinion. If you want to receive Bolsa Família, you will.” However, according to Irenaldo, only 40% of Pica-Pau’s families receive Bolsa Família. This could be due to various factors; among them the relative newness of the program and thus lack of awareness, or low levels of school attendance.

When asked directly what problems exist with Bolsa Família, Irenaldo asserted that the program fails to sufficiently educate the community: “Do you know how many students in school today, at 8, 9, 10 years old, cannot read or write? They cannot even write their own name! The problem is the education system in Brazil. Kids cannot be sitting in a chair all day. Teach them to play an instrument. Teach them to sing. Theater, sports, give them a reason to go to school.”

Irenaldo argues for the need to educate not only children, but the family as a whole. He stresses two points: “There is a lack of education and culture. Girls become mothers at 13 years old. A 20-year-old woman with no children is a rarity. If you want to eliminate poverty, increase education, modify culture… A country that invests in education and culture is a rich country. A country that fails to invest in these will be impoverished.” Advancing Brazil’s education will allow for the future generation to halt the cycle of poverty, and foster a culture of development of their socio-economic situations.

Irenaldo argues for the need to educate not only children, but the family as a whole. He stresses two points: “There is a lack of education and culture. Girls become mothers at 13 years old. A 20-year-old woman with no children is a rarity. If you want to eliminate poverty, increase education, modify culture… A country that invests in education and culture is a rich country. A country that fails to invest in these will be impoverished.” Advancing Brazil’s education will allow for the future generation to halt the cycle of poverty, and foster a culture of development of their socio-economic situations.

Not only does Irenaldo suggest there is a lack of community education, he also criticizes the lack of financial education: “To be frank…do you think families really buy what they should be buying? They do not. Do you think they care for their child better because they receive Bolsa Família? We have children running the street without even flip flops on their feet.” Due to Bolsa Família and other government assistance programs, “the people have become comfortable, dependent, de-stimulated. If you do not stimulate the people, their situation will not change.” Irenaldo’s evaluation surpasses the immediate relief that Bolsa Família may present, and recognizes the true underlying problem in impoverished communities: “We need to change the perspective of the people in the favelas, we have to change the education system.”

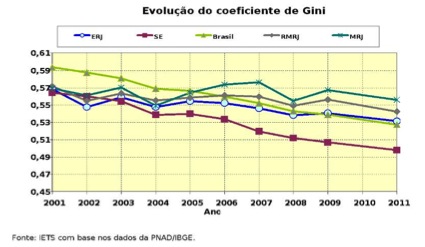

The statistics indicating the success of Bolsa Família cannot be ignored. Bolsa Família has helped millions of people cope in dire economic conditions, while simultaneously promoting social services. It has reduced inequality across Brazil (see light green line on graph). Yet Irenaldo points to a clear limitation: the quality of education, for students already enrolled in school, needs improving, as evidenced by recent reports that illiteracy in Brazil has increased for the first time since 1998. The breadth of education, too, must reach the community as a whole, in order to attain sustainable community development. Without a strong educational system, Bolsa Família may ultimately fail to achieve its long-term goal of reducing poverty. And in Rio de Janeiro, where inequality has not decreased, despite access to Bolsa Família and running counter to the national trend (see turquoise line on graph), this should be of particular concern.