What was the value in all of the years Nelson Mandela served in prison to defend the end of South Africa’s apartheid? We are now called to revisit this question after an incident in a São Paulo shopping mall became the stage for the “rolezinho” controversy. This was nothing but a group of young people, most of them black, poor and from the urban periphery, that organized a simple excursion known as a rolezinho – literally “little stroll” – to the mall, via Facebook.

It’s clear people from lower social classes are not welcome in these spaces, when not serving as cheap labor for store owners. The paradox is that the majority of people working at malls also live in the (working class) urban periphery, and when they visit these spaces they suffer the coercive power of the criminalization of poverty, which walks hand-in-hand with racism and other types of ‘isms’ that devastate human coexistence.

Differently to South Africa, segregation in Brazil is veiled and disregarded, and while it may be less cruel and divisive, we should consider the strong evidence that a perverse and malicious system established itself in Brazil since colonization by Pedro Álvares Cabral: a system that began with slavery and effects of which are still felt today. In Rio de Janeiro, the line separating rich from poor is very tenuous, and any interaction between these groups is generally seen only in a context where there is a set relationship of exercised power over the worker. Events like the rolezinho call attention to what is covered up in various settings, such as in malls, in universities, in cultural centers, etc.

There exists an Engineering of Consent that sustains the basis for the permissiveness of such mechanical constructs through systems of punishment, and it works effectively in the eyes of those who sow disunity among people. These forms of punishments or sanctions are so subtle and simple that often people do not notice when they are practiced in daily life, for the Engineering of Consent has ways of validating these actions as socially appropriate when in fact they are highly destructive. Such punishments are of a biased nature against one’s race or financial conditions, and are widely regarded as normal actions by most people.

There exists an Engineering of Consent that sustains the basis for the permissiveness of such mechanical constructs through systems of punishment, and it works effectively in the eyes of those who sow disunity among people. These forms of punishments or sanctions are so subtle and simple that often people do not notice when they are practiced in daily life, for the Engineering of Consent has ways of validating these actions as socially appropriate when in fact they are highly destructive. Such punishments are of a biased nature against one’s race or financial conditions, and are widely regarded as normal actions by most people.

Let me share my firsthand experience of what happened to me recently when visiting a shopping mall in Gávea, a prestigious high-class district of Rio’s South Zone, not far from the latest rolezinho flash mob last weekend. This is a very peculiar region where poverty and wealth are accentuated due to their geographical proximity; some of the city’s most valuable buildings and mansions are surrounded by favelas, as is the case with Rocinha and Vila Parque da Cidade, the latter being a small community inside the Gávea nature reserve where I have been living for four years. When I was recently at the said local mall, I was simply escorted by four security guards that, as soon as they saw me enter the mall, quickly implemented a prejudiced procedure upheld by fear. The entire time I shopped I was accompanied by these security guards, lasting over an hour. They would communicate by radio handsets and take turns so that the fact they were following me would not seem so obvious, but it was clear they were following and watching me as if my social or racial condition ensured a possible criminal act on my part.

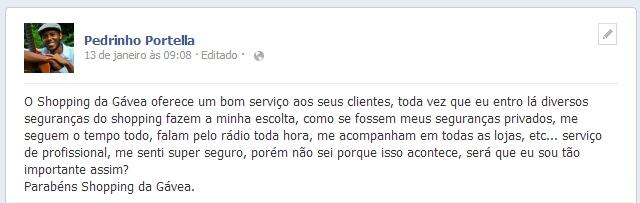

I shared the incident on Facebook with an ironic tone and there was a lot of repercussion. Many others admitted similar uncomfortable situations, sympathizing with my words:

“The Gávea Shopping Mall (Shopping da Gávea) offers great service to its clients: every time I go there, a number of security guards approach and escort me as if they were my private bodyguards. They follow me and talk to each other on their radio devices all the time, accompanying me into the stores, etc. (…) professional-grade service, made me feel highly secure, yet I don’t know why that happens. Am I really that important?

Congratulations, Gávea Shopping Mall.”

Cases like these make me believe apartheid still lives, undermining all those years of struggle by figures such as Nelson Mandela, who gave their lives for an absolute union of peoples. Small routine occurrences taking place almost unnoticed, when summed up and multiplied gain huge proportions, culminating in cases such as the rolezinho.

Pedro Portella is a Brazilian musician and sound designer born in São João de Meriti in December 1984. A student of quantum mechanics, he works professionally with startups in the areas of audio production, information architecture, user experience (UX) and design thinking. He is a resident of the Vila Parque da Cidade community.