Cidade de Deus–Working with Informalized Mass Housing in Brazil is a 2013 publication by Marc Angélil and Rainer Hehl, in collaboration with Something Fantastic, presenting a researched-based design study by the Master of Advanced Studies in Urban Design program at the ETH Zurich. Providing a case study of City of God, from historical research to an analysis on how CDD (by its Portuguese acronym) developed, from its beginnings as a planned housing project to one of Brazil’s most famous favelas, the book unveils the actual architectural processes and interfaces of the formal/informal relationship in the neighborhood.

Cidade de Deus–Working with Informalized Mass Housing in Brazil is a 2013 publication by Marc Angélil and Rainer Hehl, in collaboration with Something Fantastic, presenting a researched-based design study by the Master of Advanced Studies in Urban Design program at the ETH Zurich. Providing a case study of City of God, from historical research to an analysis on how CDD (by its Portuguese acronym) developed, from its beginnings as a planned housing project to one of Brazil’s most famous favelas, the book unveils the actual architectural processes and interfaces of the formal/informal relationship in the neighborhood.

The military dictatorship in Brazil began 50 years ago in 1964. A context of political repression emerged in Rio which saw a policy in favor of eradicating the favelas launched in 1963 by Governor Carlos Lacerda, responding to intense pressure from real estate speculators looking to gain those communities’ valuable land in central areas. The State built low-income housing projects to relocate evicted favela residents, mostly to the north and west periphery of the city. Initially barren, these areas expanded geographically and demographically with the rise of new planned settlements such as Vila Aliança, Vila Kennedy, Vila Esperança and City of God. These modernist public housing projects opened a market for mass housing in Rio de Janeiro and its suburbs, with thousands of relocated favela residents being moved there and opening the floodgates to future informal housing.

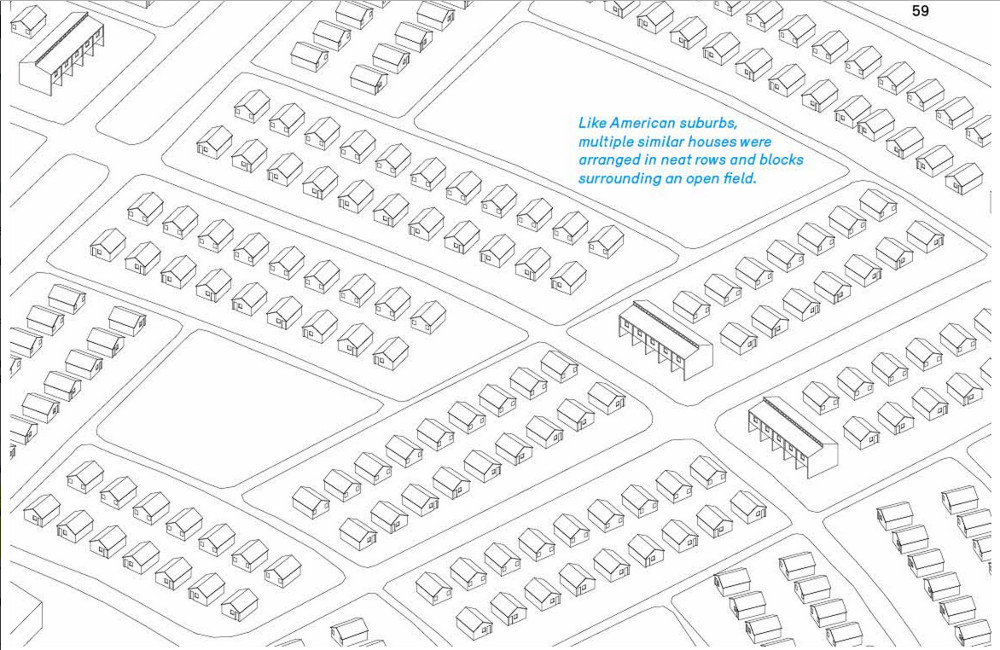

City of God as a housing project was conceived in 1964 under the architectural expertise of the Guanabara State Affordable Housing Company (COGAB-GB), financed by the National Housing Bank (BNH), and with economic and technical assistance from the US Alliance for Progress program, launched in 1961 by President John F Kennedy to promote economic growth and political reform in Latin America. Housing units began being handed over in 1966 before it was fully completed. The project was planned to house close to 10,000 people in its initial 3,053 housing units, making it the largest residential complex built by a Brazilian governmental housing company.

City of God as a housing project was conceived in 1964 under the architectural expertise of the Guanabara State Affordable Housing Company (COGAB-GB), financed by the National Housing Bank (BNH), and with economic and technical assistance from the US Alliance for Progress program, launched in 1961 by President John F Kennedy to promote economic growth and political reform in Latin America. Housing units began being handed over in 1966 before it was fully completed. The project was planned to house close to 10,000 people in its initial 3,053 housing units, making it the largest residential complex built by a Brazilian governmental housing company.

However, despite its original intention to bring an impetus of modernity to Brazilian working classes, City of God fell far short its initial goal, and witnessed a social degradation that would soon become a symptom of governmental program failures, with urban growth problems simply being shifted from a central to a peripheral location.

Moreover, the architecture and design of the project, which were viewed by many as cheap copies of middle class housing, were inadequate for the newly-occupying working class residents. The endlessly replicated single-family houses and modernist apartment blocks–the two types of housing built in City of God–were too rigid for the new residents and not planned for collective use. In Cidade de Deus, Angélil and Hehl compare this case to Cingapura, a poorly executed public housing program in São Paulo, inspired by Singaporean public housing and initiated in 1992, and parts of the current Minha Casa Minha Vida housing program, reminding us that the mistake of building socially inefficient, generic housing runs rampant to this day.

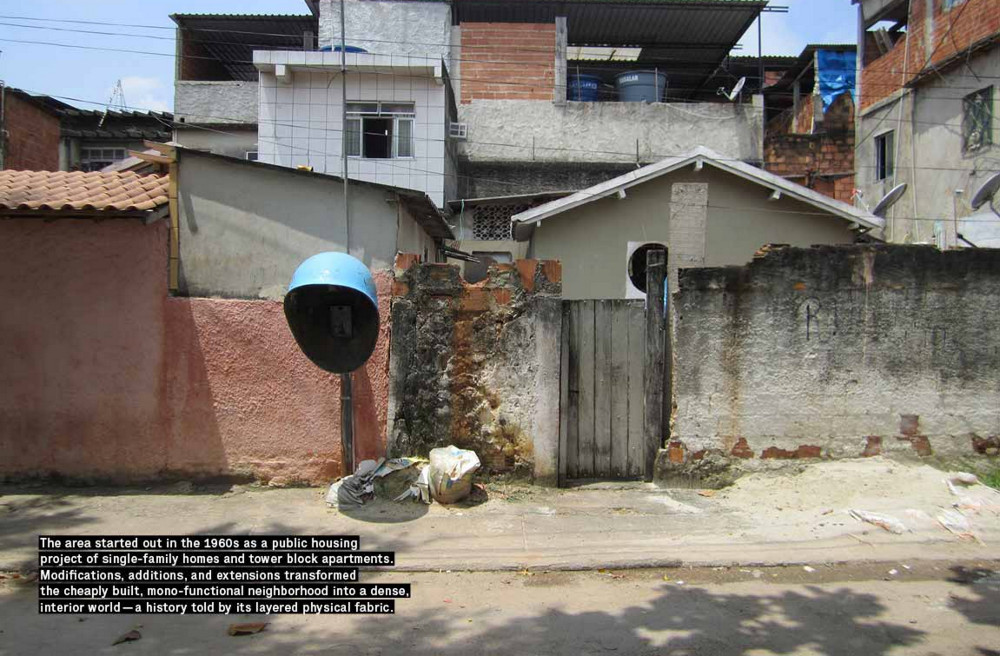

Consequently, in a matter of years after its completion, informal architectural activities took place to adapt the space to the needs of City of God’s residents. Today, an aerial view of the neighborhood would appear as rationally similar as the initial plan was, composed of geometric housing lots of equal sizes. However, City of God’s original spatial configuration is hardly recognizable in a smaller scale point of view. Through the book’s diagrams and photo collections, we see that façades have been transformed into multi-layered commercial and social interfaces for passers-by. One-story houses have developed into two to three-story structures, with architectural additions such as covered patios, terraces and verandas, forming buffer zones between public and private spaces. Kiosks, gyms, and various types of social and commercial spaces were implemented to activate the dead space in between housing units, transforming the mono-functional neighborhood into a dense and complex area, combining residential and commercial functions at different scales. Its hybridized mass as a whole can look homogenous due to limited material resources; yet no two buildings in City of God resemble one another because of their customization to specific needs.

Consequently, in a matter of years after its completion, informal architectural activities took place to adapt the space to the needs of City of God’s residents. Today, an aerial view of the neighborhood would appear as rationally similar as the initial plan was, composed of geometric housing lots of equal sizes. However, City of God’s original spatial configuration is hardly recognizable in a smaller scale point of view. Through the book’s diagrams and photo collections, we see that façades have been transformed into multi-layered commercial and social interfaces for passers-by. One-story houses have developed into two to three-story structures, with architectural additions such as covered patios, terraces and verandas, forming buffer zones between public and private spaces. Kiosks, gyms, and various types of social and commercial spaces were implemented to activate the dead space in between housing units, transforming the mono-functional neighborhood into a dense and complex area, combining residential and commercial functions at different scales. Its hybridized mass as a whole can look homogenous due to limited material resources; yet no two buildings in City of God resemble one another because of their customization to specific needs.

The book places importance on depicting City of God today beyond the common favela stigmas. In fact, having grown in an isolated and very marginalized situation at the time and therefore out of the scope of the government for many years, City of God faced important security issues during its early stages, triggered by urban poverty, social fragmentation, and the government fiscal crisis during the 1980s (known as Brazil’s “lost decade”). The neighborhood carries the infamous reputation of being a violent area until today, emphasized in Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund’s 2003 City of God movie, based on Paulo Lins’ best-selling novel.

The book places importance on depicting City of God today beyond the common favela stigmas. In fact, having grown in an isolated and very marginalized situation at the time and therefore out of the scope of the government for many years, City of God faced important security issues during its early stages, triggered by urban poverty, social fragmentation, and the government fiscal crisis during the 1980s (known as Brazil’s “lost decade”). The neighborhood carries the infamous reputation of being a violent area until today, emphasized in Fernando Meirelles and Kátia Lund’s 2003 City of God movie, based on Paulo Lins’ best-selling novel.

However, City of God today is a vibrant, growing suburban center, with a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) since 2009 and inhabited by approximately 40,000 residents. Due to the high mediatic visibility of the area, the Rio de Janeiro city government has built various collective facilities to be used for sport activities, educational purpose and other community events. But more than being just a hybrid urban environment, City of God today has a strong local identity, having its own currency since 2011 (created to stimulate local commerce) and a capacity to self-govern through community association networks.

With the 2016 Summer Olympics to be hosted in Rio de Janeiro, City of God can expect, as can many areas in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, to develop even more significantly in the next few years as their once marginalized locations become more central and strategic, close to the scheduled Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca. The forthcoming development of these areas coincides with the rise of a lower-middle class in Brazilian society, and adding to that a recent awareness about the issues of forced evictions in some informal settlements. The future prospects of these communities will be closely observed.

With the 2016 Summer Olympics to be hosted in Rio de Janeiro, City of God can expect, as can many areas in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, to develop even more significantly in the next few years as their once marginalized locations become more central and strategic, close to the scheduled Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca. The forthcoming development of these areas coincides with the rise of a lower-middle class in Brazilian society, and adding to that a recent awareness about the issues of forced evictions in some informal settlements. The future prospects of these communities will be closely observed.

From an architectural point of view, it is the intrinsic qualities of the existing site–which through flexibility provide a high residential density and a mixed land use, as well as a pedestrian and cyclist oriented traffic, reducing the amount of cars and consequently energy consumption in the district–that led the team from ETH Zurich to consider working with the informal within the community to be the key to its future sustainable development. The book projects alternative future scenarios for the neighborhood through maps and diagrams, defining different urban strategies to work with this informalized mass housing, referred by the authors as: channeling the informal (to maximize diversity); grafting the informal (to use the popular to network public spaces); underpinning the informal (to use infrastructure as a catalyst); stratifying the informal (to densify the city in layers); luring the informal (to stimulate identity through references); and embracing the informal (to negotiate an open-ended process). This ultimately results in smaller scale architectural projects aiming to upgrade the multi-family house and incremently grow semi-public courtyards and shared facilities delimited by a structural framework facilitating vertical expansion, and to upgrade the modernist towers by adding a new layer of outdoor collective space between the housing blocks.

Cidade de Deus from ETH Zurich MAS Urban Design is an essential publication covering the evolution of the neighborhood’s urbanism and architecture during a specific but very important chapter of Rio de Janeiro’s history, investigating thoroughly the use of standardized mass housing after the first relocations of evicted favela residents until today. In fact, by overcoming the lack of social qualities of its generic initial plan by producing informal spaces, City of God itself constitutes a powerful critique of the modernist principles that led to standardized rational mass housing. The book not only breaks the stigmas about the characteristics of informal architecture and urbanism, it also states that working with the potential of informality is worth exploring for the future of big cities–an idea which can be applicable not only in Brazil, but worldwide.