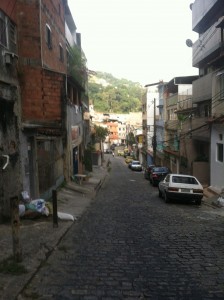

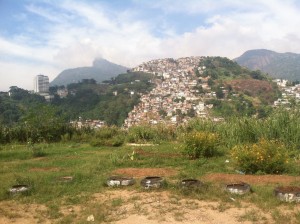

Cíntia Luna, 35 years old, current President of the Santa Teresa United Neighborhood Association (AMUST), has played a leadership role in the development of the association over the past eight years. A long term resident of Fogueteiro, one of the favelas in Santa Teresa, central Rio de Janeiro, Cíntia grew up in the community and remembers her childhood when developments began in the area. Perceiving that the community wanted and needed changes, Cíntia and other residents reinstated the association, as the first association had shut down more than twenty years prior. In our interview with Cíntia, we spoke about her history in the community, her role as president of AMUST, the changes she has made in the community and her hopes for the future of Fogueteiro.

ROW: Please tell us about your background as a social leader. What made you get involved with AMUST? Was there an event or specific occurrence that led you to engage? How was this process?

Actually, there is a story yes: we were chatting a lot in the street about the things that we could have here, the things that could change. At that time we were questioning why there was no neighborhood association, the association no longer existed. It had existed, but had closed down and we wanted to start it up again. So we started these conversations and the group started the process together. Then, we formed a panel and took stock of the situation. We started up naturally, not seriously, but it happened and now eight years have passed. And I think that lots of things have changed. We have improved what has been possible. For us, it is a really small shift, because still there are many things to improve, but since there was nothing before, it was a significant change. Many things have happened in these eight years. At first, we were ten people, and we have ended up three. Everyone already feels very tired. And it is very difficult to recruit more people. We go through things and many people criticize. No one offers a solution.

ROW: Was there an election? How was it?

There was an election in October of last year and this year there will be another. But even with little support, I believe there will be people who will want change, and things are changing.

ROW: What do you do nowadays as the president of AMUST? What is your role?

People are really confused about the role of the neighborhood association president. People think the president is a lawyer, judge, that she is from the City government, that she is from the State government, and they think that we have the power to do everything, change everything and it is not that simple. But the definition of the role is simply to listen to the demands of the majority about the problems that occur in the community, and refer them to the authorities, who have the power to make arrangements, and also to receive these authorities so they can do their work here.

ROW: What has been your biggest project to date as president of AMUST?

ROW: What has been your biggest project to date as president of AMUST?

In truth it was the Boa Safra project that we created ourselves and still maintain now as volunteers. It involved many children and teenagers, many of them on route to employment. What makes us most proud is this work that we did with children who now are young people, and we still continue with this. Our main focus is with children and youth.

We have classes in wrestling, capoeira and football. Our girls’ football team were champions in the Taça das Favelas (Favelas Cup) championship; we took part with many other Rio de Janeiro communities. Through our work with girls’ football we received an invitation for various girls to play in Portugal and France. This work was mostly focused on sport and also on education because all of them have to go to school and there’s a whole process. We have a good influence on these children and also on teenagers. It’s great.

ROW: What have been the greatest challenges that you have lived through as president of the association?

I think the greatest challenge was the implementation of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP). It was in 2011, three years ago now. And also I think that a big challenge is the relationship between the UPP and the community. It is the greatest challenge. At the moment the residents are confused about our role too, they believe that we have the power to change the captain of the UPP and the remit of the police.

ROW: With respect to the UPP, was the community willing to receive it? How has the project manifested in the community? What have been the high and low points? How would you evaluate the impact?

I believe that the majority of people support the implementation of the UPP, not the way in which the police work but rather for the change. Now we have less exposure to weapons. Today children don’t see as many firearms as they did before, when they had this view of the guerrilla. Nowadays there isn’t this view, despite everything. Children know that everything continues more or less as before. The goal of the UPP is not a bad project, the idea was really good, but over time I believe they are losing strength, losing credibility, there has been lots of talk of this. I believe the government does not want to have rogue police but there are many rogue police. This undermines the successful functioning of any police program. So there you go, I think that the UPP has its pros and many cons.

ROW: What would you do if you could change things with the UPP?

ROW: What would you do if you could change things with the UPP?

If it were possible to change something it would be the total credibility given to the police version of events. In the police force there is something called “double public faith,” that is, what a police officer says carries twice the weight of any citizen’s version. So this means that if I don’t have drugs, but a police officer says that I have drugs, in the courts his word carries more weight. So this “double public faith” places a large amount of credibility on the police, on the police officer, not on the police as an institution but on the individual officer, and we have bad police who will use this against Rio’s people. This is what happens today in communities, in which the majority are black and are victimized with arbitrary and totally wrong imprisonment. There are still many things to change.

ROW: How have the residents received you and your work?

Nowadays, I think they are no longer satisfied. Because there comes a moment when there’s nothing more we can do. There are many things that I can’t change. We are in an election year. This year we have opportunists and in this year the government won’t do anything because anything it wants to do could be used against it, because it is election year. We end up in a situation in which the residents don’t understand that there is nothing that can be done. Residents want to see results, but this only happens if they also participate in the community. I think we have a lot of work ahead of us.

ROW: What keeps you dedicated to this work after so much time?

I like to help when it is necessary, maybe that’s it. It’s difficult because at times we don’t have any financial motivation, but I’ve got the impetus to help people.

ROW: What would your ideal future be for Fogueteiro?

ROW: What would your ideal future be for Fogueteiro?

I think that Fogueteiro will continue in this way, moving on like Brazil. I hope that people wake up and see that there is no future with only one person. There is only a future with the collective. If the communities of Rio de Janeiro were to unite, they would change Rio de Janeiro, because we are the majority, but the majority of the hill are ignorant to the potential they have. I hope that the population of Fogueteiro wakes up and takes the initiative to shout louder.

ROW: Finally, what would be the most important advice you would give to a young person who is frustrated with the state of things or who is interested in engaging with social issues?

That they transform all of their frustration, rage, anger into knowledge. Because it is only with knowledge that they will be able to fight. If they revolt without knowledge they will be just another statistic.