Since the period of transition from military dictatorship to democracy in the 1970s and 80s, Rio de Janeiro’s reputation for social, political and spatial division has only become more consolidated. The city became infamous for its high crime rates. Repeated public security crises in the past decades have helped the consolidation of this image and culminated in the securitization of its urban spaces. The 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games became an incentive for a transformation of this picture. In this context, the 2008 police occupation of Santa Marta marked the beginning of a new public policy approach based on what was said to be a community policing program: the Pacifying Police Units, or UPPs.

Some of the UPP program’s goals are to re-integrate favelas into the ‘formal’ city; to promote citizenship in them by establishing peace and democracy; and to expand the presence of the public and private sectors in favelas. They also aim to counter the view of Rio as a ‘divided city’ and break its ‘logic of war.’ However, the UPPs take place within a broader state of affairs that absorbs and therefore influences them. This context includes preconceptions about citizenship, criminality and space. When we look at the UPP program against the background of Rio’s historical material and symbolic segregation, it becomes clear that the UPPs have serious limitations.

Citizenship in Rio

Space is a formative structure historically produced by human agency in a political process. Citizenship and space are intimately linked, articulating matters of exclusion and inclusion through categories such as race, gender and class. There is both a symbolic and material distancing between types of citizens in Brazil. James Holston in Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil explains that whilst Brazil’s democracy since the 19th century has been one of formal universal membership in the nation-state, substantial rights are unequally concentrated as the privilege of certain social categories. Social differences are thus applied to legally distribute inequality. One example of this is the law regarding prison cells, which allows prisoners with a university degree a separate cell from ‘common prisoners’ without one. This enduring ‘inclusively inegalitarian’ citizenship, as he calls it, is both expressed in and shaped by the city’s spaces.

Space is a formative structure historically produced by human agency in a political process. Citizenship and space are intimately linked, articulating matters of exclusion and inclusion through categories such as race, gender and class. There is both a symbolic and material distancing between types of citizens in Brazil. James Holston in Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil explains that whilst Brazil’s democracy since the 19th century has been one of formal universal membership in the nation-state, substantial rights are unequally concentrated as the privilege of certain social categories. Social differences are thus applied to legally distribute inequality. One example of this is the law regarding prison cells, which allows prisoners with a university degree a separate cell from ‘common prisoners’ without one. This enduring ‘inclusively inegalitarian’ citizenship, as he calls it, is both expressed in and shaped by the city’s spaces.

It is also expressed in popular discourses of crime and (in)security in Brazil. Teresa Caldeira’s much acclaimed City of Walls explored Brazil’s “disjunctive democracy” in what she named the manichaeism of the ‘talk of crime.’ She found that Brazilians apply this discursive strategy to deal with their daily encounter with insecurity, on the rise since the 1970s–the re-democratization period. It articulates essentialized images of the criminal, dividing Brazilians between those who are ‘good,’ ‘cultured,’ ‘moral,’ and ‘of a proper family’ and those Others who are ‘poor,’ ‘mentally weak,’ ‘promiscuous’ and ‘evil.’ This discourse sees the spaces associated with crime, such as favelas, through an environmental determinism. Their residents are always perceived as potential criminals, at the margins of society and humanity. She also understands this discourse to present a challenge to the strengthening of democracy, because it cultivates the existing relationships of privilege.

Caldeira found that Brazilians often blame public institutions–for example Brazil’s failing judicial system–for the increase in crime and violence, diagnosing the need for more police authority or to “take matters into their own hands.” This extrapolates into investments in private security and gated communities, into attacks on human rights, into support for abuses by the police, for vigilante groups and into justifications for the death penalty. Protecting criminals’ human rights is here interpreted as allowing them the privilege of having such rights. The ‘talk of crime’ is a narrative of fear that illustrates the race and class privilege under which Brazilian democracy operates, a democracy that carries authoritarian conceptions of public order supporting the eradication of thieves to eliminate the “impurity” of the national character.

The rise of tenements and later favelas since the end of slavery was a complex process closely linked to social, political, cultural, economic and spatial transformations in Brazil in the second half of the 19th and first half of the 20th century. The First Republic’s urban modernization plans to open avenues and renovate the city’s spaces in the image of Europe evicted poor Brazilians whilst failing to provide alternative housing. Poor and black cariocas were understood as an impediment to progress, so that until the 1970s Rio’s governments repeatedly attempted to remove favelas.

The rise of tenements and later favelas since the end of slavery was a complex process closely linked to social, political, cultural, economic and spatial transformations in Brazil in the second half of the 19th and first half of the 20th century. The First Republic’s urban modernization plans to open avenues and renovate the city’s spaces in the image of Europe evicted poor Brazilians whilst failing to provide alternative housing. Poor and black cariocas were understood as an impediment to progress, so that until the 1970s Rio’s governments repeatedly attempted to remove favelas.

Since then, re-democratization and a new notion of civil rights halted the discussions on removal and instead endorsed favela upgrading projects such as Favela-Bairro. This period of re-democratization was one of complex transformations–such as inflation, political instability, increases in crime, and poverty–which created in Brazilians a sense of uncertainty and chaos, as Caldeira also explores in her book. A rise in segregationist initiatives in housing and public space was also part of this picture. The neighborhood of Barra da Tijuca is illustrative of this, full of highly surveilled gated communities and shopping malls that re-conceptualize public space. These “fortified enclaves” encourage a division with the rest of the city for being exclusive, controlled and homogeneous private properties for public use.

The emergence of favelas and fortified enclaves is linked to exclusionary ideas about a desirable city, a socio-spatial segregation that leaves unclear who is being excluded from where. Rio therefore faces a problem of inequality beyond material wealth and with complex links with crime. Much work has been done to challenge the conventionally held view of a straightforward causation between material poverty or income inequality and crime. Symbolic segregation affects public security policies because it not only limits social mobility, but, in the words of Jennifer Pierce in her 2008 paper ‘Divided Cities: Crime and Inequality in Urban Brazil,’ “distorts the effect of deterrence measures, leaving the poorest sectors more vulnerable to becoming both the victims and perpetrators of crime.” This has, of course, material consequences.

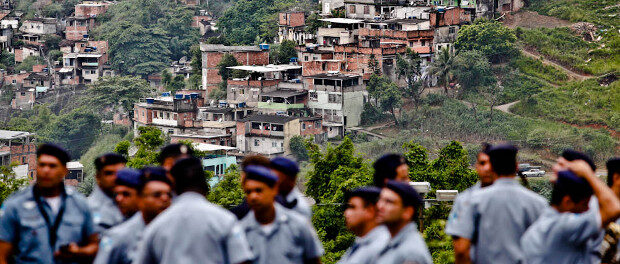

Rio’s Militarization in the State of Exception

Within this context of sociospatial segregation and since the rise of drug factions in Rio’s favelas in the 1980s, the city has been increasingly militarized under an ‘urban war logic’ that seems to implicate everyone. A number of public security crises widely covered in the media in what sociologist Michel Misse called the “cycles of social accumulation of violence” that date back to the mid-1800s have led to the normalization of a culture of fear and horror. Brazil’s authoritarian tradition has stimulated police institutions to maintain “order” no matter what. The Military Police, whose current militarized culture and behavior is a product of the dictatorship, dominates in patrolling the streets. Policemen are trained as ‘soldier warriors’ facing an internal enemy–the drug traffickers. When Brazil became involved in the UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti and announced the intention to host the upcoming mega-events, Brazilian authorities made the decision in 2008 to apply to the domestic ‘humanitarian crisis’ what had been learned there.

The UPP program emerged from this background as the lesson learned from previous public security policy failures and successes. They are installed in phases, from the invasion of the favela, the establishment of permanent UPP police stations in them to the co-operation with the UPP Social program aiming at the favela’s social development. The UPPs represent favelas as spaces ‘of lack’–lacking sanitation, education, security, etc.–as ‘war zones’ and as the spaces of crime. The discourse in the media, especially when federal troops were deployed to help the program, was one constructed around the dichotomous confrontation between the ‘police warrior, defender of freedom’ and the ‘evil illegitimate criminal oppressors.’ Caldeira’s ‘talk of crime’ functions in these representations as a discourse that objectifies the criminal and justifies public security policies.

The UPP program emerged from this background as the lesson learned from previous public security policy failures and successes. They are installed in phases, from the invasion of the favela, the establishment of permanent UPP police stations in them to the co-operation with the UPP Social program aiming at the favela’s social development. The UPPs represent favelas as spaces ‘of lack’–lacking sanitation, education, security, etc.–as ‘war zones’ and as the spaces of crime. The discourse in the media, especially when federal troops were deployed to help the program, was one constructed around the dichotomous confrontation between the ‘police warrior, defender of freedom’ and the ‘evil illegitimate criminal oppressors.’ Caldeira’s ‘talk of crime’ functions in these representations as a discourse that objectifies the criminal and justifies public security policies.

Hence, we can observe in the UPPs a discourse of crisis and exceptionalism. The inhuman treatment of criminals and favela residents, when perceived as always already potential criminals, is rendered unproblematic in this state of exception through an Othering process legitimized in a historically and culturally constructed “regime of truth” regarding citizenship that leads to the militarization of the spaces associated with these subjects. The treatment of favelas as war-like spaces, and the public’s tolerance for ‘collateral effects’–especially at the early stages of the UPPs–show favelas as a zone where the outlaw does not have rights. This drawing of lines between ‘truly human’ and inhuman subjects, however, does not work towards organic integration or democracy.

Therefore, the symbolic segregation under which Rio operates limits the long-term effects of any military victory, for it leaves the lines that divide the city unchanged in their content. Criminals and potential criminals continue to be de-humanized as enemies, declared unprotected by the law. Although public policies like the UPPs can mean a new type of citizenship for those favela residents who can prove that they are ‘honest workers,’ the criminals and potential criminals remain stripped from their rights. The Amarildo case serves here as an example of how this distinction is easily blurred, making it the responsibility of the potential outlaw to prove himself as a worthy citizen. This is because securitization always works through drawing lines between those inside and those outside of the polity, so that even when we can shift those lines, we cannot get rid of them completely. This Othering process maintains the status quo of Brazil’s ‘disjunctive democracy’ despite material changes.

Therefore, the symbolic segregation under which Rio operates limits the long-term effects of any military victory, for it leaves the lines that divide the city unchanged in their content. Criminals and potential criminals continue to be de-humanized as enemies, declared unprotected by the law. Although public policies like the UPPs can mean a new type of citizenship for those favela residents who can prove that they are ‘honest workers,’ the criminals and potential criminals remain stripped from their rights. The Amarildo case serves here as an example of how this distinction is easily blurred, making it the responsibility of the potential outlaw to prove himself as a worthy citizen. This is because securitization always works through drawing lines between those inside and those outside of the polity, so that even when we can shift those lines, we cannot get rid of them completely. This Othering process maintains the status quo of Brazil’s ‘disjunctive democracy’ despite material changes.

The military and social phases of the UPPs try to simultaneously cover crime deterrence and prevention through military occupation and later poverty relief within a discourse of development. But the UPPs in some ways reinforce symbolic segregation through the assumptions they articulate. They focus on the drug factions, the criminals and the spaces associated with them, instead of looking at the complex illegal networks of crime that do not only take place in favelas, that cross licit and illicit activities and that include but are not exclusively made up of non-state actors. The UPPs reinforce support for the death penalty articulated in the ‘talk of crime’ since criminals or potential criminals can only be fought with lethal measures that increase the likelihood of their death. Military action and economic relief would on their own not foster the type of coming together that would organically break down the existing divisions in the city. That is because firstly, explanations of why people resort to crime and violence that focus only on economic circumstances do not grasp the whole picture. Secondly, the securitization of an issue removes it from public debate and decision. The issue becomes de-politicized, closing up opportunities for alternatives to be imagined.

Conclusion

The UPPs leave a legacy of what is acceptable in the city’s ‘marginal spaces.’ Militarizing a space creates a negative peace–something recent developments have already begun to undermine–and normalizes a state of conflict. The UPP Social, in turn, should open up opportunities for bottom-up projects such as social movements and NGOs, and with them the opportunity to challenge the prevalent discourse. The existing criticisms to the UPPs are proof this is happening. Nevertheless, calling such problems ‘social’ is a discursive strategy employed by liberal popular and scholarly discourse alike. Relegating favelas to the ‘social’ realm takes them away from problems of politics and so de-problematizes them.

The UPPs do not successfully capture all dimensions of the problem of public (in)security in Rio since space, culture and security intersect in complex ways. Top-down approaches like the UPPs rarely get to the bottom of the problem. What we can conclude from this analysis is that Brazil requires a re-thinking not only of the executive and judicial power, but also of its sociability patterns in order to re-politicize the matter at hand. The UPPs do not offer a magic solution to public security issues. For favela residents, it has the potential to create and has created many opportunities, but this process has to involve the whole city. It is the relationship between historically mutually constructed spaces that has to be problematized, not the isolated dynamics within one space only–the favelas. As one Brazilian once said: “As long as the poor are killing each other, the social and political balance stays the same.” Focusing exclusively on the criminals and the state apparatus is overlooking the relevance of the complex dynamics that cross several of Rio’s spaces, racial groups and classes, which both affect and are affected by the current situation. We must be critical not only of the state and the drug traffickers–we must be critical of ourselves.

Désirée Poets was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro and has been undertaking her PhD at the University of Aberystywh, Wales, where she also completed her Masters in Postcolonial Politics. Her interests lie in urban political mobilizations, currently with a focus on race and ethnicity in urban spaces.