The Comitê Popular da Copa e Olimpíadas do Rio de Janeiro (Rio Popular Committee on the World Cup and Olympics), just published its third Mega-Events and Human Rights Violations Dossier. The 173-page report presents an updated analysis of preparations for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics.

The first dossier, launched in March 2012, intended to “shed light on the instances of human rights violations” related to the mega-events. This was followed by a second dossier in May 2013. The editions detail the impacts of preparations on housing, infrastructure, workers, public security and policing, and the environment, among other issues. The latest dossier, released just in time for the opening World Cup match, examines the same social and economic issues of its predecessors, focusing especially on violations of resident and worker rights.

The first dossier, launched in March 2012, intended to “shed light on the instances of human rights violations” related to the mega-events. This was followed by a second dossier in May 2013. The editions detail the impacts of preparations on housing, infrastructure, workers, public security and policing, and the environment, among other issues. The latest dossier, released just in time for the opening World Cup match, examines the same social and economic issues of its predecessors, focusing especially on violations of resident and worker rights.

New Developments

Over the past 12 months, Rio has seen its fair share of turbulence. The Comitê Popular’s report examines the events of the past year, focusing on the effects of the June 2013 protests, the unprecedented victory of the street sweepers’ strike this past Carnival, continued removals and community resistance in targeted favelas, and the increasingly troubled Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program . The latest dossier on Mega-Events and Human Rights Violations in Brazil outlines violations in government’s approach to development and policing, evidencing an overarching lack of popular participation and dominance of private business interests.

The dossier presents recently released data, with updated statistics on removals and UPP operations, as well as a breakdown of costs and funding sources for both the World Cup and the Olympics. The report also provides a month-by-month timeline of the Committee’s work and involvement in popular resistance initiatives from 2011 to 2014. This report details a whole host of human rights violations and illegalities committed in connection with the coming mega-events. But the Comitê Popular also emphasizes that beyond just exposing violations, the report should serve as an invitation to take action, to advocate for more responsive and representative governance.

Housing

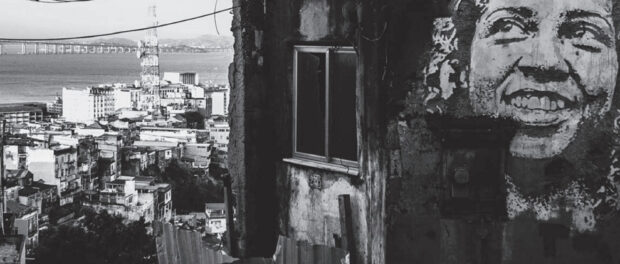

The report argues that removals and forced evictions are the “most concerning and violent form of violations to residents’ rights” and that government removal and pacification tactics represent a form of social cleansing. Removals are concentrated in areas of extreme real estate speculation, namely in Barra da Tijuca (site for the 2016 Olympic Park), the Center, and the South Zone.

The report argues that removals and forced evictions are the “most concerning and violent form of violations to residents’ rights” and that government removal and pacification tactics represent a form of social cleansing. Removals are concentrated in areas of extreme real estate speculation, namely in Barra da Tijuca (site for the 2016 Olympic Park), the Center, and the South Zone.

“In all cases, removals went forward without residents having access to information justifying the necessity of the removal and without any discussion of the urbanization projects with either residents or the wider community… as established by the City Statute… communities have the right to participate in the decision-making process with regard to government interventions in their areas.”

The report presents a collection of removal summaries for each favela, organized by reason for eviction–Transcarioca, Transoeste, or Transolímpica BRTs construction, the Porto Maravilha regeneration project, alleged area of risk, or environmental protection, among others. This information is condensed into a clean table, showing 38 favelas that have been either removed or threatened, organized by time period and ostensible reason for removal.

The Comitê Popular also offers a list of government practices that can be classified as human rights violations, including: absence of information for communities; lack of resident involvement in discussions about government proposals; no guarantee of access to adequate resettlement in a nearby area; undermining community organizations and insisting upon negotiations with individual families, often arbitrary and without clear terms; use of tactics of coercion, threats, and intimidation; treating residents as second-class citizens without rights.

The Brazilian Constitution clearly guarantees the right to housing, and Brazil is signatory of a variety of international human rights conventions, including Res. 1993/77 of the UN Human Rights Commission, which affirms that the “practice of forced eviction constitutes a gross violation of human rights.”

The housing chapter concludes with ‘popular victories’: a list of successes for communities. While some favelas have secured guarantees from the government that they will no longer be targeted for removal, at least for now, (Tubiacanga, Parque Royal, Portuguesa, Barbante, Estradinha, Indiana), more commonly successes were limited, ranging from reduced removals (Providência, Arroio Pavuna) to increased compensation for removals (Largo do Tanque) and options for nearby resettlement, rather than relocation to the far-West Zone Minha Casa Minha Vida housing projects (Metrô-Mangueira, Vila Autódromo).

Key Eviction Statistics:

4,772 families, 16,700 people in total, have been removed as documented by the Comitê Popular

29 communities have been removed as witnessed by the Comitê Popular

75% of removals documented by the Comitê Popular are due to World Cup/Olympics-related development projects

4,916 other families from 16 communities are currently known to be at risk of removal by the Comitê Popular

Infrastructure: Where Has the Money Gone?

The dossier outlines the course of infrastructure projects that have gone forward in preparation for the World Cup and the Olympics. For the city with the worst traffic congestion in the Americas, the chance to reform Rio’s infrastructure was initially met with optimism, heralded as a ‘revolution.’ But as the report details, many projects have gone over-budget, are behind schedule, or have been abandoned altogether. The Comitê Popular asserts that while delays and costs are concerning, even more problematic is the government’s guiding intention for these projects:

The dossier outlines the course of infrastructure projects that have gone forward in preparation for the World Cup and the Olympics. For the city with the worst traffic congestion in the Americas, the chance to reform Rio’s infrastructure was initially met with optimism, heralded as a ‘revolution.’ But as the report details, many projects have gone over-budget, are behind schedule, or have been abandoned altogether. The Comitê Popular asserts that while delays and costs are concerning, even more problematic is the government’s guiding intention for these projects:

“An analysis of investments in the city of Rio de Janeiro indicates that these investments [in infrastructure] are not aimed at the city’s neediest areas or those which present the worst indicators of mobility.”

With the bulk of funding going towards airport upgrades and the Transcarioca, Transolímpica, and Transoeste bus rapid transit lines, current projects will connect the Olympic Park site in Barra da Tijuca with the Center and South Zone. The dossier argues that these investments serve the short-term financial interests of developers rather than the long-term health of Rio’s residents, especially those living in the city’s transportation-starved outskirts.

Key Infrastructure Statistics:

300% rise in real estate prices in Rio since 2008

R$8 billion – current cost of World Cup stadiums, R$2 billion over budget

R$25.8 billion (USD $11.6 billion)– current total 2014 World Cup spending

R$36.6 billion – current estimate for total 2016 Olympics spending, with a new cost breakdown made available in January 2014

R$7 billion for Rio 2016 Organizing Committee (COJO), funded by private sector, responsible for food and transportation for athletes, security, game costs

R$5.6 billion for Responsibility Matrix, public/private funding, construction of sports facilities

R$24 billion for Public Policies Plan (Legacy Plan) of which 13.7 billion public (federal, state, and local) and 10.3 billion private (public-private partnerships)

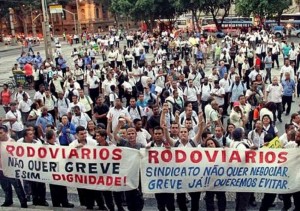

Labor and Sports Privatization

This section of the Comitê Popular’s report outlines a host of abusive employment practices, unsafe conditions, and an overall lack of inspection and regulation of the infrastructure projects for the World Cup and Olympics. Along with details about specific projects, the report also outlines the process of stadium privatizations. The privatization of Rio’s iconic Maracanã Stadium, designated in 2000 as one of Rio’s Cultural and Historic Heritage sites, gets special mention. According to the report, privatization threatens football’s social and cultural tradition of participation and accessibility.

This section of the Comitê Popular’s report outlines a host of abusive employment practices, unsafe conditions, and an overall lack of inspection and regulation of the infrastructure projects for the World Cup and Olympics. Along with details about specific projects, the report also outlines the process of stadium privatizations. The privatization of Rio’s iconic Maracanã Stadium, designated in 2000 as one of Rio’s Cultural and Historic Heritage sites, gets special mention. According to the report, privatization threatens football’s social and cultural tradition of participation and accessibility.

Because of skyrocketing ticket prices, a seat in a World Cup stadium is now a luxury many Brazilians can no longer afford. And since FIFA has exclusive rights to the sale of World Cup merchandise, none of Rio’s estimated 60,000 informal vendors can legally take home part of the profits. What’s more, due to new legislation, these vendors will not be allowed within a 1000m radius of Maracanã stadium during the World Cup.

Key Stadium and Privatization Statistics:

0 – percent tax rate FIFA must pay on income from the sale of World Cup merchandise

R$1.6 billion – cost to public coffers for renovations to Maracanã Stadium over the past 15 years

Maracanã Stadium capacity reduced from 150,000 seats to 73,000 seats over the course of renovations

R$12.2 – average ticket price in 2007

R$30.6 – average ticket price in 2013

R$720 – minimum monthly wage for 2014

R$250-800 – ticket prices for 2013 Brazil Cup final

R$330-1,980 – starting ticket prices for 2014 World Cup final match for Brazilian citizens

The Environment

This section of the dossier explores the relationship between environmental impacts and mega-event preparations, exposing significant inconsistencies in the government’s commitment to environmental issues. Environmental concerns have been repeatedly cited as reasons for removals in favelas, especially in areas of real estate appreciation. The dossier argues that many of these assertions are merely catch-all justifications for removals. Where a basic lack of sanitation and infrastructure coincides with legitimate concerns–think raw sewage draining into Guanabara Bay–they can addressed without removals.

This section of the dossier explores the relationship between environmental impacts and mega-event preparations, exposing significant inconsistencies in the government’s commitment to environmental issues. Environmental concerns have been repeatedly cited as reasons for removals in favelas, especially in areas of real estate appreciation. The dossier argues that many of these assertions are merely catch-all justifications for removals. Where a basic lack of sanitation and infrastructure coincides with legitimate concerns–think raw sewage draining into Guanabara Bay–they can addressed without removals.

In Vila Autódromo, residents put together an award-winning urbanization plan with two local universities to take into account environmental risks, but the community is still slated for removal. Arroio Pavuna, bordering construction for the Transcarioca line, is also under threat of removal, despite the SPU’s ruling in favor of residents. Meanwhile, the government has neglected to consider environmental impacts caused by construction for the World Cup and Olympics. Impacts caused by the rapid transport construction have not been satisfactorily studied.

The dossier presents a startling example of the government’s plans to build the 2016 Olympic golf course in an environmentally protected stretch of forest in Barra da Tijuca, despite the opposition of a Technical Support Group study. Members of Golfe Pra Quem? (Golf for Whom?) formally denounced the plan to the Public State Ministry (MPE), but the project is still in the process of licensing.

Overall, the dossier highlights the way the government has repeatedly used environmental concerns as a tool to facilitate removals while ignoring these same concerns with respect to public works projects.

Public Security and Policing

Focusing on recent developments in favela policing, the Comitê Popular expresses concern that recent UPP tactics during favela operations resemble older policing tactics, notorious for their violence and impunity. With abundant examples, the report cites instances of police intimidation and arbitrary violence by UPP police. Additionally, a table organizes the location and circumstances of all 21 confirmed deaths caused by UPP forces between June 2011 and May 2014.

Focusing on recent developments in favela policing, the Comitê Popular expresses concern that recent UPP tactics during favela operations resemble older policing tactics, notorious for their violence and impunity. With abundant examples, the report cites instances of police intimidation and arbitrary violence by UPP police. Additionally, a table organizes the location and circumstances of all 21 confirmed deaths caused by UPP forces between June 2011 and May 2014.

The dossier contends that, besides violating favela residents’ rights, policy surrounding the coming mega-events violates the entire public’s rights. Law 6363, better known as the World Cup Law, was passed in December 2012. Violating established Brazilian law, the World Cup Law creates a state of exception that extends 20 days before until 5 days after the World Cup – during this time no one without FIFA’s approval can be in official competition sites, which include stadiums but also parking lots, training centers, fan leisure centers (like parts of Copacabana), media centers, and airports. Additionally, the World Cup Law, violating the Access to Information Law, permits increased phone tapping and social network monitoring. New Anti-Terrorism Laws also put harsher penal codes in place for the period during the World Cup and loosen grounds for arrest to include subjective terms like ‘causing panic or fear.’

Key Security Statistics:

21 people killed by UPP forces from June 2011-May 2014

1 out of every 23 people arrested by police in Rio are killed

The Comitê Popular’s third dossier on Mega-Events and Human Rights Violations in Brazil provides an exhaustive look at the patchwork of issues at play in the preparations for the World Cup and Olympics. Ultimately, the dossier calls upon the government to work toward a Rio that is “founded upon public, democratic debate, that upholds the rights to housing, that respects workers’ rights, that preserves the environment, and most importantly, in which the welfare of the people comes before the interests of big business.”