Rio de Janeiro is increasingly investing in its museum infrastructure, with three new world class museums launched or programed in recent years; the Rio Museum of Art opened in 2013, in the city’s historic Port area; the Museum of Image and Sound programmed for Copacabana beach; and the controversial Museum of Tomorrow also in the Port. However, Rio also boasts some incredibly innovative and fascinating community museums, which reimagine the conventional idea of museology just as the communities in which they are located have ardently challenged and overcome the conventions of formalized neighborhoods, neither with much help from the State. They blend past, present and future, placing a huge importance on retaining memory but also looking forward, or as is written on a wall on Estrada de Gávea in Rocinha, “with feet planted firmly forward and head looking back.”

MUF – Museu de Favela

The Museu de Favela (MUF), in the Pavão-Pavãozinho and Cantagalo communities that overlook Copacabana and Ipanema beaches, was founded in 2008, one year before the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) was installed in the area. It is a territorial museum, where the extensive mass of resourcefully built homes is the display case and the “20,000-or-so residents and their cultural traditions are the archive.” The museum is “alive” in the sense that it grows and changes along with the community and its inhabitants.

A related attempt at an “open air” museum was made in Providência, Rio’s oldest favela, by City government in 2007, but there was no further investment or initiative on the part of the authorities. Rather, Providência residents are mounting their own museum today.

The MUF, however, is a growing initiative of a group of residents who came together to document and recognize the history of the community, creating “the world’s first favela territorial museum,” and taking visitors on systematic excursions with the aim of urban, cultural and socio-economic development reaching all of the residents and simultaneously inviting people from all nationalities to get to know the rich cultural and historic heritage.

MUF’s vision is to transform the community into a “Carioca touristic monument” to share the history behind the formation of favelas and northeastern migration, the cultural origins of samba and capoeira and more modern developments such as street art. In contrast to degrading forms of favela tourism, whereby residents and their homes are gaped at from the “safety” of open-topped Jeeps, MUF offers favela tours which invite tourists to interact with the community on a personal level and witness the incredibly tight-knit bonds that spread throughout.

Unlike some other territorial museums, MUF has a physical center as well. They hold cultural events such as capoeira shows and cinema screenings with help from both Brazilian and foreign volunteers through links they have with the Pontifical Catholic University (PUC) and Rio’s Federal University (UFRJ). Oli Moraes, an Australian volunteer from PUC, says, “MUF’s location in the heart Cantagalo enables outsiders and locals to come together to share and witness the community’s history and culture. From the first day of volunteering at MUF I have felt welcomed and at home, and the people I have met there have changed my perception of Rio.”

Promoting waste reduction is also a priority of MUF; they collect and reuse bags and packaging from shops in Ipanema and nearby buildings in the favela. They also have a gift shop, which sells eco-friendly souvenirs, all made by local craftsmen. Check out MUF on Facebook.

Museu do Horto

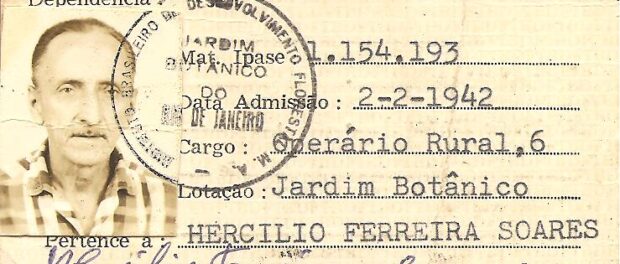

The Museu do Horto, or Horto Museum, also had a space to hold events, but only until recently. During the 19th century, employees of the Botanical Gardens were given permission to build within the Gardens’ limits and thus the Horto community was born. Many of the families living there today are direct descendants of these workers and have been fighting to remain since 1990, when the garden institution began claiming the land back under false allegations of land invasion. The community recently lost the Clube Caxinguelê in this fight, a leisure space built in the 1950s that the Horto Museum and community in general used for its events. The club was seized by the Gardens in order to make room for a new greenhouse.

For now, the museum is territorial and online. Their online museum collates texts, photos and videos, ranging in subject from music and sport to politics and resistance. The online archive of memories is vital in retaining the history of the community and asserting the rights of the residents. With a social objective based on ‘new museology,’ they aim to rethink the idea of a traditional museum. According to Horto resident and one of the museum’s coordinators, Emerson de Souza, they are creating “a more socially dynamic and participatory form” in a territory where there is “a real need to preserve the community cultures that suffer from speculation and the eventual destruction of its land, people and cultures.” Check out Museu do Horto on Facebook.

Museu da Rocinha Sankofa

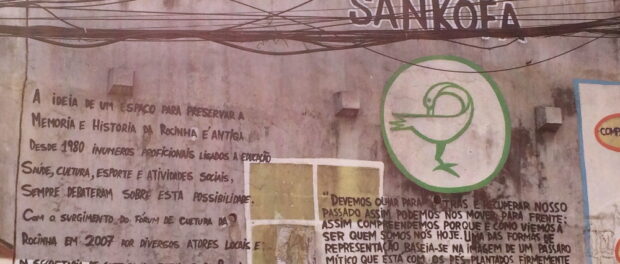

Much like MUF and Horto, the Museu da Rocinha Sankofa is principally territorial and bases its philosophy on that of ‘new social museology.’ In 2004, during the presidency of Lula da Silva, the Ministry of Culture started a Live Culture Program, promoting initiatives of cultural diversity within Brazil. Since its foundation, Sankofa has been in the construction process to create a Point of Memory and Culture, and works on several fronts. Antonio Firmino, one of the museum’s coordinators, believes that having a fixed space is important and they are currently using the Rocinha Public Library for a photography exhibition pairing portraits of current and early 20th century street sellers in Rocinha.

Again like MUF and Horto, the Sankofa Museum compiles and documents the experiences and memories of the older residents, with particular importance placed on women. Antonio says, “People tend to base history on facts and figures, but a story that denies orality denies reality.”

Territorially, the museum is also very active. It promotes street art and its historical explanation; one of its current projects is the history of Rocinha displayed in graffiti on a large wall on Estrada da Gávea. They are also working on what Antonio refers to as “guided historical visits,” to take groups through the favela, explaining the history behind the plethora of street art and different cultural and historical points within it, and most importantly, as with MUF and Horto, allow visitors to enter and interact with the community.

The common theme of holding onto memories in order to look forward is one that Sankofa adheres to. Antonio explains: “We need to look back and retrieve our past so we can move ourselves forward: thus we understand how and why we came to be as we are today.” Check out Sankofa on Facebook.

Museu da Maré

Located in the North Zone of Rio, the Museu da Maré tells the extraordinary history of the city’s largest favela complex. The wall on entering the museum reads, “If life counts itself in years, days and hours, on clocks and calendars, in this museum it is told through periods where nothing is finished, everything is in transformation. Past, present and future coexist in the periods of water, resistance, home, work…” The museum is laid out in 12 aspects of the favela history and life, from faith to fear, with descriptions painted on the walls accompanied by artifacts, photographs, reconstructions of traditional favela homes and even a recreated rickety wooden walkway which used to keep residents out of the water that flooded their community built on the edge of the Guanabara Bay. Artifacts, video and photographs from the Museum were central to last year’s Favela Design exhibition at Rio’s Studio-X.

Higor Antonio, a history student, researcher, teacher and lifelong resident of Maré, places huge importance on the “next generations being able to have direct contact with the past… so they can contribute to the construction and strengthening of a local identity.” The Maré Museum project allows residents “to remember a time of suffering and what was the beginning of the construction of what we know today as Maré.” The museum allows residents of Maré to remember and understand what their relatives and friends did, often in the face of adversity and with constant threat of violence or removal, to make their community the vibrant place it is today. Check out Museu da Maré on Facebook.

Pretos Novos

Instituto Pretos Novos (New Blacks Institute), located in Gamboa in Rio’s Port Region, is a memorial to the many thousands of African slaves who perished during or after the tormentous ocean crossing, before being sold into slavery, many of whom were no older than 15 years of age. Their bodies were buried in a mass cemetery, which is estimated to be the largest slave burial site in the Americas, with up to 30,000 buried there. In 1996, after buying a home in the Port area, Petrúcio and Maria de la Merced Guimarães discovered human bones while working on the foundations of their new house. After calling the police and later archaeologists, and realizing that their house was built on an archeological site of such tragic significance, they founded the museum to honor the memory of the “New Blacks,” or newly arrived slaves.

“It is a place of memory and respect for a history that has been hidden for 200 years… it is important that people don’t forget,” says Merced. “It represents an important crime against humanity.” The museum tells the moving story of the Pretos Novos along the walls, paired with pictures, a short documentary and two excavations in the floor where human remains can still be seen, skulls broken as they were packed in. It is an incredibly harrowing experience, and one that should be witnessed by all; as Maria affirms, a tragedy such as this that has played such an extensive and detrimental part in Brazil’s history and can still be felt in the social, cultural and economic fabric of Rio today, cannot be forgotten. Check out Pretos Novos on Facebook.