The World Cup 2014 and the preceding leadup have seen an unprecedented level of attention to Brazil’s favelas. Much of the conversation has been productive, magnifying and expanding debates around top-down interventions, police violence, favela tourism, gentrification processes and assets of favela communities. Above all, residents’ voices have been given a bigger international platform than ever before.

From television, the BBC’s three-part ‘Welcome to Rio’ series forefronted the stories of individual residents in order to explore ‘peace,’ ‘war,’ and ‘ingenuity’ in favela communities and push back on the image of favelas as dangerous no-go areas. From print and online news, The Guardian, Al-Jazeera, and n+1 Magazine all published pieces that situated favela residents as agents of change within their communities, an important step in moving away from past (and lingering) trends of casting poor citizens as passive objects of development. Journalists such as Dave Zirin actively sought out the stories in danger of slipping under the radar, spotlighting demolitions and historic eviction struggles at Favela do Metro and Vila Autódromo while calling on colleagues across the media to stop underreporting the continuing protests throughout the World Cup. We saw a fascinating example of how the international media can influence national conversations, as articles reflecting on racism and racial inequality in the stadiums from The Globe and Mail and The Guardian sparked a renewed discussion about race in Brazil in the national media and on social networks.

While broadly there have been considerable advances in the way favelas and their residents have been reported on during this period of intense attention on Brazil, examples of lazy and prejudiced journalism which perpetuates old stigmas, casts Brazil’s low-income citizens as ‘the other,’ and fails to seek out quotes and insights from favela residents have continued throughout. In the rest of this article, we dissect some of the most egregious reporting to emerge during the World Cup as we kept track of reporting during our #RioCupWatch campaign.

CNN – Experience this favela and explore the other side of Brazil

Right from the title, this CNN article establishes a false dichotomy between two “sides” of Brazil. One side is light and happy, the “glistening beaches” and “exuberant fans” that can be seen from “thousands of miles away.” In contrast, the favelas “lurk ominously over Rio’s natural splendors” as Brazil’s “underbelly.” According to the article, this is “the other” side, the “different dimension of Brazil [that] languishes in poverty, succumbs to violence and struggles with drug abuse.” Not only does this description not actually mention people, referring instead to this vague “dimension” of the country, but it strips community residents of any individual agency by portraying them as passive victims, overcome by their environment and drugs.

Unfortunately, this article is one of many that have eschewed nuance in favor of a black-and-white portrayal of the realities of Brazil. ‘A visit to Rio’s underbelly’ from Asian Age lumps all favelas together as uniformly dangerous and, despite insightfully acknowledging that “it would be wrong to brand every favela dweller a drug peddler,” still paints its residents as either criminals or “graveyard shift” workers. This disregard for complexity is a tendency in the media that risks encouraging the same disregard for nuance in policy-making and development projects.

The Daily Beast – Rio’s real-life slumdog millionaires

This unfortunately-titled article from The Daily Beast reports that improved security brought about by the government’s Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program has transformed the residents of Vidigal’s ocean-view properties into a “new legion of unintentional real estate tycoons.” The author wonders whether residents should “sell now and cash in their millions, or hold tight for a chance to make even more.” Without providing a single quote from a resident of Vidigal, the author assumes that residents must be looking to play this “ultimate game of real-estate roulette” and sell their way out of the community he portrays as an undesirable living environment. However, as examples from favelas across the city have demonstrated, many people choose to turn down significant amounts of money in order to remain in their communities.

Failing to recognize the assets of favelas, as this article does, leads to policies that seek to remove neighborhoods entirely rather than work with inhabitants to improve them. Furthermore, the author fails to explore the implications of the real estate speculation on rental tenants in the community, nor the reality that, rather than a real estate gold mine, Rio’s favelas are the city’s affordable housing stock and designated ‘zones of special social interest.’ The author does not provide a single example of a resident who has successfully sold a home for millions. By glorifying the new market opportunities available to residents, this piece minimizes the very real threats of gentrification and Vidigal’s efforts to debate and formulate community-led responses to this phenomenon.

news.com.au – Inside Rio de Janeiro’s favelas: the man with the gold-plated gun

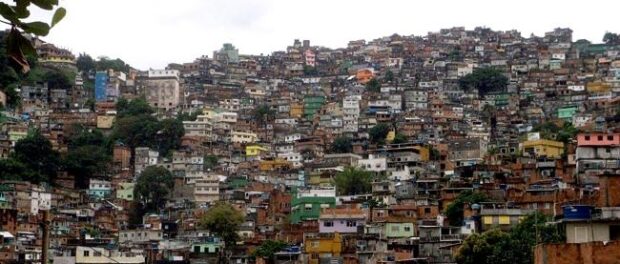

This article on the favelas begins with the important statement that “Brazil’s slum areas, or favelas, are portrayed to the outside world as being dangerous. No-go zones.” Unfortunately, the author then continues to provide exactly that portrayal, emphasizing the presence and control of drug gangs and discussing security in Rocinha without mentioning its UPP program. To describe a local representative of the Amigos dos Amigos gang, he writes: “More enforcer than counselor, I suspect he subscribes to the ‘speak softly and carry a large semiautomatic machine gun’ school of management.” This play on a well-known expression may have some tongue-in-cheek intent, but the self-acknowledged “suspicion” is supported by no evidence and is explained no further. The author never shares the insights of the “tattooed lady” guiding him. He describes wanting to ask a woman in the bakery about life in the favela, but apparently decides not to bother.

These decisions are mirrored by a number of journalists who visited favelas only to fail to interview residents and focus the resulting piece on their reflections as a visitor. A writer for the Irish Times describes the favela he visits as “an environment so tenuous and so hostile it is a wonder anyone can persevere with it,” but does not investigate how residents persevere, or whether they might have something positive to say about their environment. While one writer at canada.com describers her “great pleasure” at “finding a few boys kicking a ball in a concrete playground with expressive murals,” another at The Score describes people who “exist in cramped, haphazard almost medieval poverty” in an environment where “single-parent families of eight or nine children live in one and two-bed shacks made of wafer-thin bricks” and “seven year olds are not supposed to have high hopes.” Unfortunately, this style of reporting, whereby the journalist’s own prejudices, expectations and limited impressions are projected into their representation of a place, wastes an opportunity to give a platform to the voices and ideas of favela residents, who already struggle to be heard in debates about their own lives.

Gulf Times – A doctor’s house call in a favela

At the beginning of the World Cup the Gulf Times published the reflections of a US-based doctor who visited Rocinha. Several other platforms have republished the story, including Counterpunch, Japan Times, and glowbi, leading to the circulation of this piece among different audiences throughout the duration of the tournament. The doctor falls into the same trap as the journalists who reported on their visits to communities without reporting any community perspectives. He presents information that is both false–such as his statement that police are “normally unable to enter favelas”–and stigmatizing–for example the assertion that “favelas house many people involved in drug trade and other crimes.” Did the doctor think it would make for a less compelling piece to admit that favelas house many more people who are not involved in drug trade and other crimes? His story about having to check in with men at each “level” of the favela in order to “reach the upper level alive” simply does not reflect the experience of most visitors to Rocinha. It is unfortunate that this sensationalist story was given multiple platforms from which to influence readers around the world.

In spite of these and other examples of unproductive reporting, the overall impact of pieces produced during the World Cup period has been positive, moving the debate around favelas forward by reaching a wider audience with more nuanced scrutiny of policies and projects affecting favelas. RioOnWatch has tracked the international media discourse on favelas over the last four years and it is apparent that the trend over time is towards greater inclusion of favela residents’ voices. Looking ahead to the 2016 Olympics, it will be essential that journalists and commissioning editors continue this trend of using the international spotlight responsibly to further reduce, and ultimately end, the stigma faced by Rio’s favelas and thus pave the way for inclusive policies that actually take residents into account and thus improve their lives. Such reporting would be of service to informal communities globally.