Up to 250 people are currently sheltered in the gymnasium of Our Lady of Loreto Catholic Church, near Rio de Janeiro’s international airport, over three months after being violently evicted from the abandoned Oi/ex-Telerj site in the North Zone. With nowhere to go and dependent on donations, the group claim to be victims of low wages and increasing rents in a situation that has intensified during the preparation periods for the World Cup and Olympic Games.

The group, who self-identify as the ‘Telerj community,’ are the remainder of the spontaneous occupation of 8,000 that occupied the abandoned industrial space in Engenho Novo for 12 days in April. The eviction on April 11 drew international attention after military police used violent tactics to evicted the occupying families, including young children, just weeks before the start of the World Cup.

A second violent eviction from outside a municipal administrative building on April 15, and a third negotiated eviction from outside the city’s Cathedral on May 3, discouraged many families from resisting further. Many returned to their original communities to seek refuge with friends or family.

With nowhere to go, some families had no other option but to remain within the movement. The remaining 250 are living in rudimentary conditions, with their survival dependent on donations from the Catholic Church. Food barely feeds everyone everyday, and diapers, powdered milk, and essential supplies for children are scarce. One resident referred to their degrading living conditions by showing how he ate his food by scooping it up with his hands in the absence of forks.

Seventy tents stand in rows in the gymnasium, and three urinals and three ladies toilets serve the entire community. Families share space, clotheslines, and their limited possessions. The community works together to keep the space clean, sanitized, and free from illness, but infestations of rats, mosquitos, and visiting monkeys still cause problems.

One resident, Vitor, explained how living with people from such eclectic communities has been awkward and at times created tensions. Indicating to one man across the room, he explained, “I’ve lived in the same community as this guy for 30 years,” and then pointing to a woman mopping the gymnasium floor he, “But this woman, I’ve only known for 60 days.” He went on to describe the varying levels of trust between residents in the fledgling community.

The leaders of the local communities who had formed the leadership of the original Telerj community no longer accompany the movement. The current leader, former trafficker Rodrigo Moreira, explained he did not know their whereabouts.

Speaking at a recent event hosted by city councilman Renato Cinco, Rodrigo voiced his belief in the importance for the community to continue resisting, to battle against unfaithful government promises and call for accountability, and to denounce violent and repressive tactics of government security forces.

Claiming assistance

Many in the community lost their documents in the commotion of the first eviction, leaving them without necessary social security or taxpayer numbers to register for the government’s social programs. At the start of June, those without documents were assessed by government officials, and told it would take eight weeks to analyze the information to discern who they were and which social programs they might be entitled to.

But far from the tourist beach neighborhoods and busy commercial center, the Telerj community’s bargaining power in their fight for housing has been significantly reduced. The City government, holding most of the cards, is due to conclude its analysis by the end of July.

At a public hearing on May 30, the Sub Secretary of Special Social Protection at the Municipal Department of Social Development, Rodrigo Abel, claimed that 569 households from the initial Telerj community had already registered through the federal government’s Cadastro Único (CadÚnico) registration program, by using their retained documentation. From this group, Abel stated, 482 had been granted Bolsa Família, or the local complementary program, Carioca Family Card.

Rosa, who remains part of the Telerj community, explained that she did not want Bolsa Família handouts as they are insufficient to cover rising rents.

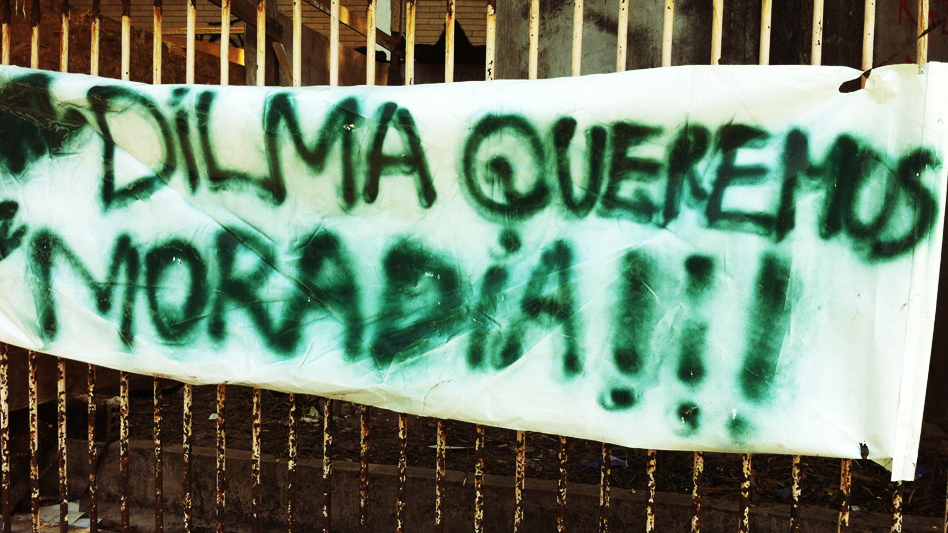

Though the principal demand of “We want housing!” is identical now as to what it was in April, only 20 families had been registered to a housing program, according to Abel.

Many of the social programs, such as Minha Casa Minha Vida, Bolsa Familia, Carioca Family Card, Bolsa Carioca, Social Rent (a rent aid program of up to R$400 per month for a maximum 12 months), and various subsets of these programs are all being considered as solutions.

In 2012, President Dilma Rousseff, Mayor Eduardo Paes, and ex-Governor Sérgio Cabral promised to build 2,240 apartments on the Oi/ex-Telerj site, to be known as Bairro Carioca II. However, after more than two years of negotiations, the deal is still incomplete and no further public information has been made available.

There is nothing to suggest that the Telerj community who are successful in receiving Minha Casa Minha Vida will be allocated housing on the Oi/ex-Telerj site. In the meantime, the families sheltered at the Our Lady of Loreto Catholic Church wait.