President of the Organizing Committee for the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, Carlos Nuzman recently remarked that “Rio 2016 is intensifying its relationship with society.” He continued, “The Games will leave a huge legacy for both Rio and Brazil… No other host city will have had such a big transformation from the Games as Rio.”

The social impacts of the 2016 Olympics are indeed intensifying; whether that is a boon to Rio’s residents, however, is, to put it nicely, highly disputed.

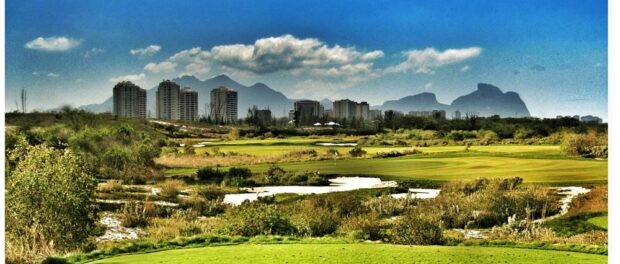

The Olympic golf course is the perfect microcosm through which to identify much of what is wrong with the approach to Olympic infrastructure development in Rio. It is emblematic of the ways in which Rio’s preparations for the 2016 Games are deeply problematic.

The site chosen for the golf course sits on 1 million square meters of protected Atlantic Forest on the edge of the Marapendi lagoon in Barra da Tijuca. A mix of fragile mangroves, marshes, and sandbanks, the area contains about 300 identified species. A whole host of different animals will be threatened by new development in Marapendi, from herons to capybaras to endangered species such as the yellow-necked alligator, the beach lizard, and the crested guan.

In order to gain access to the golf course land parcel, Rio’s City Council passed Complementary Law 125 in late December 2012, during an emergency session just before their holiday recess.

The passage of Complementary Law 125 raises grave legal concerns. In order to free up this land for the course, legislative norms and democratic, participatory processes were either undermined or directly violated.

The passage of Complementary Law 125 raises grave legal concerns. In order to free up this land for the course, legislative norms and democratic, participatory processes were either undermined or directly violated.

The City government bypassed an array of laws, from the federal Atlantic Forest Law and Forest Code to municipal laws that designate most of the land as an Area of Environmental Protection (APA), subject to strict sustainable land-use guidelines. The remaining portion of the parcel was part of the public Marapendi Municipal Reserve, an area under “permanent protection,” theoretically off-limits to any and all development.

Given these protections, the law passed in December 2012 is extreme in its provisions. First, it authorizes the construction of the golf course within the borders of the Marapendi Reserve, using the justification that building a golf course qualifies as sustainable use of the land. Additionally, it redraws the borders of the Marapendi Municipal Reserve in order to completely cut out the section that fell within the intended golf course site. The law effectively nullifies the area’s “permanent protection” status, handing this piece of public land over to a private developer, RJZ Cyrela.

Given these protections, the law passed in December 2012 is extreme in its provisions. First, it authorizes the construction of the golf course within the borders of the Marapendi Reserve, using the justification that building a golf course qualifies as sustainable use of the land. Additionally, it redraws the borders of the Marapendi Municipal Reserve in order to completely cut out the section that fell within the intended golf course site. The law effectively nullifies the area’s “permanent protection” status, handing this piece of public land over to a private developer, RJZ Cyrela.

The crowning provision of Complementary Law 125 gives developer Cyrela full rights to build 23 new 22-story luxury condominiums on-site in exchange for shouldering the R$60 million contract for the golf course. Besides clearly failing to meet the sustainable-use guidelines–which charge any construction within the APA’s bounds with “protecting the biological diversity and ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources”–this also runs counter to previous zoning regulations, which had capped construction to individual residences and select 6-story buildings.

Cyrela now has construction rights in what amounts to some of Rio’s most highly valued real estate. Apartments in one of these new high-rises are on the market for up to R$16 million ($7 million USD) each.

Federal and state elections are coming up in October, and contractors and developers have long played an important role in financing political campaigns in Rio. Cyrela happens to be the city’s largest real estate developer.

There were no environmental impact studies either, nor was an environmental management program formulated–both required before licensing can be approved. There were no public hearings to Complementary Law 125, also in violation of the law.

Current development in Barra da Tijuca owes much to Lucio Costa‘s ideas about what a ‘modern utopia’ should look like: sleek high-rise apartments, shopping malls, and wide high-speed avenues. Real-estate agency RVM boasts that Barra is “emerging as the playground of Rio’s trendy and affluent.”

In 2010, according to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Barra da Tijuca held only 2.1% of total households in Greater Rio but 8.1% of aggregate household income. By comparison, the four largest favelas held 2.5% of total households but only 1% of aggregate household income.

The concentrated development of the Barra region has drawn criticism from specialists. “The World Cup and the Olympics gave the City government the excuse to totally diminish every aspect of responsible urban planning in Rio de Janeiro,” argues Professor Fernando Walcacer, former City Prosecutor for Urbanism and the Environment. “We’re going to pay dearly for this.”

Marcello Mello, a biodiversity gestation specialist, declares that “political authorities and business interests in Rio de Janeiro have been uniting to cash in on development in the city’s last green spaces.”

Others are more optimistic. In a recent article on NBC’s OlympicTalk site, Nick Zaccardi writes: “The next two years, and the last five years, are not a burden but an opportunity for the city to prove its mettle as a bellwether for expanding the Olympics to new areas.”

This kind of ‘mega-event as metric of progress’ conception is naïve at best and harmful at worst. It legitimizes an attitude of ends justifying the means when it comes to government preparations for mega-events such as the Olympics or the World Cup, eliding the damage caused by feckless policy.

According to Andréa Redondo, an architect and former president of the City Secretary of the Preservation of Cultural Patrimony, “The [government’s] discourse is very seductive, but the project is just a real estate tool at its core.”

Gentrification and the rising cost of living continue to push lower-income residents out to the urban periphery. In one of the largest removals since 2009, 876 of the 1,500 families in the Vila União de Curicica favela nearby in Curicica, West Zone, are slated for removal to make way for Olympic infrastructure projects. And families living for generations nearby in harmony with the urban forest of Pedra Branca are fighting eviction.

Meanwhile, Cyrela’s Riserva Golfe website boasts about the amenities in the golf course condominiums: up to five parking spaces per apartment. One building includes a 1,308 square meter penthouse, serviced by six elevators, two bedrooms for maids, and a master bedroom intended for a governess.

These apartment high-rises are billed as “Rio de Janeiro’s most exclusive address.” Cyrela’s website promises, “Here, you and nature live together in perfect harmony.”

Houses in favelas generally occupy less than 80 square meters.

This project codifies the government’s prioritization of private business interests over those of Rio’s citizens and reinforces the driving factors of social and economic inequality. It sends a strong message that a lucrative real estate deal is worth more than the health of the city’s democratic process, hard-won environmental regulations, and the rights of the people to legislative participation.

The social and political implications of this project extend far beyond concerns about construction delays and environmental consequences, though the latter is especially concerning. While the golf course project is certainly not the first instance of regressive, environmentally damaging development decisions in Rio, it represents a particularly harmful combination of violations.

Sociedade do Bem, an NGO focused on advocating for the “common good,” is currently litigating a public civil lawsuit against the City government. The case is stalled, and according to their lawyer Jean Carlos Novaes, their chances of stopping the golf course project are “very remote.”

Instead of his intended promise of progress, Rio 2016 President Nuzman’s talk of transformation reads much like a warning. Indeed, a continuation of top-down development decisions, peppered with legal irregularities, licensing violations, and a total absence of public participation, exemplified by the Olympic golf course case, will only consolidate Rio’s reputation as a city governed by and for the wealthy, at the expense of everyone else.