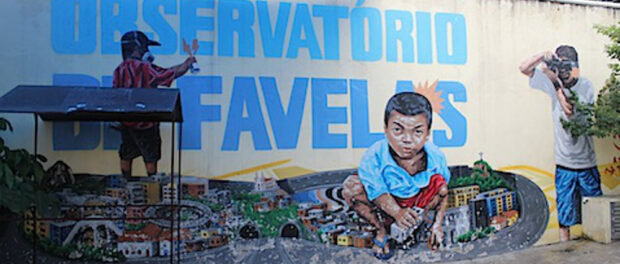

On Thursday August 28, the Favela Observatory hosted a seminar in Complexo da Maré to launch the official publication of the Right to Communication & Racial Justice project. The project promotes community access to media production in order to increase recognition of the relationship between institutional racism and the violence experienced by Afro-Brazilians, favela residents and low-income communities.

The Favela Observatory is a social organization that undertakes research, consultancy and public actions to disseminate accurate knowledge on the issues affecting favela communities. Their project mapped 118 alternative/community-based media sources in the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area between 2013 and 2014 to produce a report on their capacity to fight racism. The 130-page publication includes everything from research methodology, case studies of media outlets, academic essays on race and gender, and the sustainability of community initiatives.

The objective was also to increase the depth of the 2011 Media in Favelas project that tracked community reporting in the city.

The composition of Rio de Janeiro’s neighborhoods demonstrates a stark ethnic and social stratification in which people of African descent are overly represented in more deprived areas and more likely to be victims of crime. According to the 2010 census, 47.7% of Brazil’s population identify as white and 50.7% as black or brown. But in favela communities only 30% of residents are white and 68.3% are black. Whilst the homicide rate amongst white males has been declining for years, the opposite is true for young black males. Between 2002 and 2010, the homicide rate amongst young black males increased from 30 to 35.9 murders per 100,000 people–meaning that in 2010, a black male was more than twice as likely to be murdered than his white counterpart.

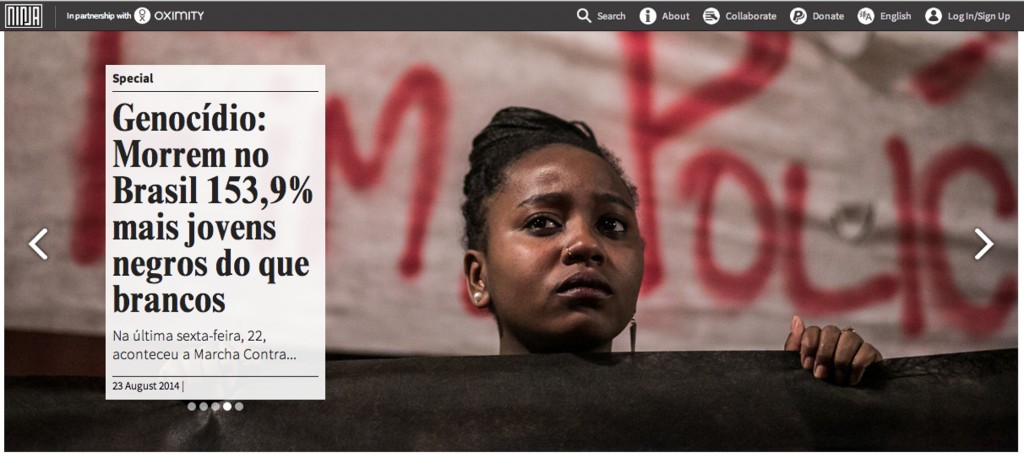

The Favela Observatory notes that the mainstream media’s lack of focus on the violence affecting Afro-descent communities is part of a process that marginalizes the importance of black lives. Whilst the murder of Michael Brown has forced the United States to confront its complicated race relations, lethal police brutality in Brazil often passes without comment. After a few days of protest, anger and broken families, the machine of institutional racism and media intransigence rolls on.

The seminar included a panel discussion with Sueli Carneiro (feminist and Afro-Brazilian rights campaigner), Joel Zito Araujo (award-winning film director/producer) and Marcelo Paixão (professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and specialist on racial inequality) who each spoke about how lack of space for black Brazilians to present their own experiences in the media contributes to the normalization of violence.

They praised the role of accessible media in the struggle for recognition and the Afro-Brazilian narrative, and established that heightened media visibility leads to a stronger political presence.

By ignoring an issue, the media reduces the issue’s importance in the eyes of decision-makers and the general public. It also indicates a tacit acceptance that violence against black people is the natural order of things. This naturalization of systemic violence allows the often brutal policing of low-income communities to violate people’s rights with impunity.

The Right to Communication & Racial Justice Project is working to strengthen community voices who can produce and disseminate counter-narratives from their own point of view whilst giving young people in favela communities opportunities for development. Increasing visibility will help break the symbolic and physical violence that dehumanizes Brazil’s black communities.

The project has three key objectives:

- Produce and diffuse knowledge about the level of democracy in communication and media, considering communication as a fundamental right in the fight against racism.

- Contribute to the construction and consolidation of public policies that democratize communication, support accessible media, and form a network of stakeholders who work with favela and periferia (peripheral neighborhoods’) communication.

- Focus on spreading knowledge about favela/low-income neighborhoods with cooperative media that will contribute to fighting racism.

Out of the 70 community initiatives profiled in the publication, 74% are online resources whilst the other 26% include radio, printed press, and other audiovisual outlets, demonstrating the growing importance and accessibility of social media and the blogosphere.

The publication used Mídia Ninja as a case study of online activism. This outlet gained notoriety in 2013 when it tweeted and blogged in real time about the widespread protests sweeping Brazil. The Favela Observatory describes Mídia Ninja as “one of the expressions of the relatively recent transformations, in which the model of authorship, solely based on accessing web-pages, has given way to profiles that balance receiving and sharing a larger volume of information.”

As the Right to Communication & Racial Justice publication states: “Paying attention to different stories and the way they develop is a huge challenge for those who dedicate themselves to social transformation. The Internet has discovered huge modifications and yet-to-be defined capabilities, much like every technology that involves open channels of communication. To articulate this ever-changing phenomenon is essential. Today’s young people who were born, raised, and formed within this movement, have an unparalleled importance and must be considered as a well of untapped potential.”

“It is our duty to bring resources, knowledge and studies together in order to build a process that views young people as creative, powerful and collaborative actors in a movement. This challenge is for people who are looking to foster active citizenship suited to the characteristics of the 21st century. One that can support poorer communities who suffer disproportionately from the gross inequalities in our society.”