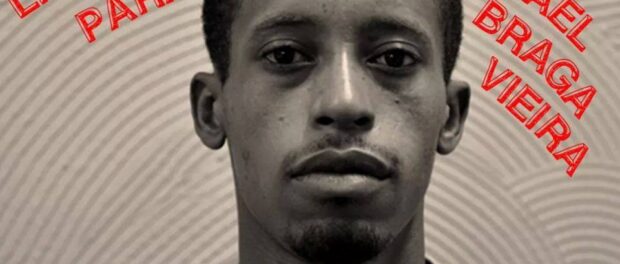

A debate held on August 20 at Rio’s Fluminense Federal University (UFF) sought to explore the issues of police violence and the criminalization of poverty and social movements in the wake of the widely disputed conviction of Rafael Braga Vieira. Braga, 26, is a black homeless man who was taken into custody after he was found in the possession of two plastic bottles of liquid detergent during the mass protests in June 2013. He was found guilty of carrying an “explosive or incendiary device, without authorization or in breach of legal or regulatory determination.”

The event welcomed Thiago Melo, lawyer and director of the Human Rights Defenders Institute, Police Commissioner Orlando Zaccone, and Henrique Vieira, theologian and City Councilor, to discuss the issues surrounding the relationship between police and civilians.

The mechanisms of criminalization

Melo provided a wide scope of criminalization mechanisms, in various facets which are not solely judicial. He broke down the concept of ‘criminalization’ into several types of discrimination that work to delegitimize the most vulnerable groups of people in society:

- Caricaturization: depicting vulnerable members of society as worthless or despicable;

- Disqualification: distorting protesters’ and movements’ agendas, proposals and claims;

- Inferiorization: diminishing orders of numbers and statistics;

- Invisibilization: reducing diversity (for example, failing to recognize the existence of different groups);

- Individualization: disregarding collective claims, shrinking them to individual ones instead;

- Co-optation: buying, absorbing or neutralizing actors;

- Omission: endangering state-provided protection systems of lawyers or magistrates.

Melo’s approach describes a varied process involving actors (e.g. politicians, certain media outlets) with a common goal of silencing struggles, disempowering and repressing parts of society, while appealing to and gaining the consent of the privileged rest.

The expediency of emergency

The justification of such maneuvers can only be achieved with a well-constructed and sustained claim to a “state of emergency,” explained professor and theologian Henrique Vieira.

Vieira retraced some of the steps and episodes that led to the current normalized “emergency” in dealing with mega-events controversies.

To emphasize the depth of ‘crimi-litarization’ in Brazilian history, Vieira read excerpts from an 1888 National Congress speech. The “poor and vicious classes” are blamed of all evil in society, and “even when vice is not accompanied by crime,” the sole condition of poverty “constitutes a rightful reason of terror for the society.”

This rhetoric was repeated when Vieira deconstructed a 2008 TV commercial where an armored vehicle drives up a favela, dropping off the police first and all other public agents (doctors, social workers, etc.) second. A voice proclaims: “Security: the entrance door for citizenship.”

As the audience contributed to the discussion, the concluding remarks called for a redefinition of peace, and for the democratization of the police–by means of transparency, accountability and checks on power. It was also concluded that the “war on drugs” must end and that the establishment must shift to alternative solutions like legalization and regulation, based around the concepts of autonomy and health.

The case of Rafael Braga Vieira

Framed in this context, Braga’s five year sentence (reduced to 4 years and 8 months after human rights association DDH appealed on his behalf) for the crime of carrying cleaning products illustrates how any underprivileged member of society could fall victim the ‘crimi-litarization’ machine.

In the words of State Deputy and head of the State of Rio’s Human Rights Commission, Marcelo Freixo: “Rafael Braga Vieira is young, black, poor, illiterate, homeless, from the peripheries of Rio de Janeiro. He doesn’t represent an exception, but a norm.”

To further illustrate Braga’s case as a norm for young black people in Brazil, it is important to note that he was the only person to be convicted for a crime during the 2013 protests.

“It’s not possible to stay blind, deaf and mute in the face of gross injustice,” said Freixo at the Rio State Legislative Assembly plenary session on August 26. “[Braga] is another one: one more invisible, poor, vulnerable, black, illiterate person that our logic of justice has condemned to what seems to be the only destiny left [to him] in our market society. That is, the prison system.”

Braga’s case symbolizes the apex of a normalized and institutionalized system of discrimination that is very much alive in Brazil.