This article is a revised version of a paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Geographers (Tampa, FL. April 2014)

An architect recently described the Morar Carioca program as “the greatest unfulfilled promise” in Rio de Janeiro. Over the past few years, we have seen this ambitious and visionary favela urbanization project get packaged into the Olympic legacy framework, co-opted by political interests, and then abruptly dismantled without sufficient explanation.

In 2010, Mayor Eduardo Paes included the Morar Carioca program as a centerpiece of the social legacy for the 2016 Olympic Games. Formally an extension of the Favela-Bairro program, Morar Carioca would have been the most comprehensive program of its kind in the city’s history, building upon a generation of accumulated architectural and technical expertise. Through participatory on-site favela upgrading and with a budget of R$8 billion, the program pledged to integrate every favela into the formal city by the year 2020. The large-scale works would include the improvement of sanitation systems, installation of water drainage systems, street lighting, road surfacing, the construction of public green spaces and recreational areas, improvement of transportation networks, home stabilization, and the construction of social service centers.

“Morar Carioca, as it is written on paper, is an urban planner’s dream for favelas,” said Theresa Williamson, urban planner and director of the NGO Catalytic Communities. The plan includes an impressive participatory model, on-site upgrading that recognizes prior investments made by residents, a focus on sustainability, and special “social interest” zoning parameters to maintain areas for affordable housing. “This would have been a real legacy, not only for Rio but [as a model] for cities around the world,” she added.

Anthropologist Mariana Cavalcanti describes the launch of the program in 2010 as “a very hopeful and optimistic time” in which a series of emerging social, infrastructural, housing, and policing programs in favelas promised to radically transform Rio de Janeiro. During field research in 2012, architects and urban planners expressed a sense of urgency and excitement. They envisioned that the Morar Carioca program would redress disparities in urban infrastructure and service provision, imagining the ways that urban design could alter patterns of spatial segregation and social exclusion in the “divided city.”

In December 2010, the results of the Institute of Brazilian Architects (IAB) design contest were announced and 40 architecture firms were selected to intervene in designated favela “groupings.” The first group of eleven firms were contracted in June 2012 and began performing qualitative diagnostics in the communities with the support of iBase, an NGO that was contracted by the Municipal Secretary of Housing (SMH) to hold participatory meetings and collect residents’ demands. But suddenly and without warning, the City cut iBase’s contract in January 2013, financially dismantling the projects and leaving SMH without an effective methodology to communicate with the communities.

Within a few years of the program launch, “the whole set up unraveled,” Cavalcanti recalls, as Morar Carioca was dismantled and its brand re-appropriated to serve other political purposes.

The weakening of a dream

Two years ago, the Mayor proclaimed that urbanizing all the favelas of Rio de Janeiro by 2020 would be a central aspect of the Olympic legacy. He promoted this message to an international audience during an April 2012 TED talk, in which he proclaimed that “the city of the future has to be socially integrated” and explaining that “favelas are sometimes a solution.”

“Now he is not saying this anymore,” said Pedro da Luz Moreira, former program coordinator and current president of the IAB’s Rio de Janeiro chapter. There has been an “emptying of the program and a weakening of its capacity.”

In January and February of 2014, I conducted a series of follow-up interviews to discover the “official response” to the question: what happened to Morar Carioca? Although fragmented versions of the project are still underway—including a re-appropriation of the program label onto a series of interventions that do not adhere to the participation methodology—the original vision to integrate the city’s favelas as part of the Olympic legacy appears to have failed, given that funding and participatory structures were oriented around the 2016 deadline.

When Mayor Paes was questioned about Morar Carioca at an event in 2013, he cited lack of financial resources. But follow-up interviews with architects and urban planners offered more cynical explanations, often coded in the language of shifting political agendas, balancing priorities and competing interests.

Pedro da Luz Moreira stated that Morar Carioca “was taken off the political agenda,” describing a Mayor who abandons a project based on his political purposes. Interviewees described a series of “bottlenecks” that impeded the program, which ultimately resulted in “a revision of Morar Carioca and its goals,” as one respondent tactfully explained.

Antônio Augusto Veríssimo, former Coordinator of Planning and Projects for SMH, explained, “We (SMH) didn’t make the decision… all orders to suspend [the contracts] came from the top down. It was a direct order from the Mayor.” When asked about the remaining architecture firms, he added carefully, “We did not have a green light from the Mayor to contract the rest of the teams,” describing a “deceleration” of the program as money was diverted to other agendas.

Several critics suggested a connection between the most active months of the Morar Carioca program and the Mayor’s reelection campaign in late 2012, during which he frequently promoted the Morar Carioca program. Anthropologist Mariana Cavalcanti imagined that the Mayor suddenly woke up after his reelection and felt the pressure of the 2016 deadline, causing him to readjust his priorities. But she added that the Mayor has right-wing instincts and that “Morar Carioca is nowhere near top of his priorities.”

Even now, explanations for the program’s dismantling remain murky to those who seek comprehensive information about the program and encounter a description on the Olympic City website that calls the Morar Carioca program “a true revolution in terms of social integration,” and still identifies the program as one of the most important Olympic legacies in the city. What remains apparent is that an ambitious program that boasted community participation and citywide integration was dismantled in the absence of dialogue and transparency.

Meanwhile, despite minimal implementation, Morar Carioca won the Siemens Sustainable Community Award, and the Mayor himself are being celebrated internationally, evidencing the successful media campaigns that have obscured the sad reality of the program’s dismantling.

Lack of “political will”

Several respondents understood the shelving of the program as the harsh reality of local politics: the Mayor is committed to a series of interests, while managing the temporal, financial, and spatial requirements of a massive quantity of public works in the lead up to the next international sporting event. But these justifications are insufficient for those communities that received the participatory phase of Morar Carioca and are now being slated for removal.

Vila União de Curicica is one such community that went from hope for urbanization under Morar Carioca to the threat of complete removal for the Bus Rapid Transit system (BRT – a system being implemented for the 2016 Olympics) in just two years. Mariana Cavalcanti was an anthropologist with the firm contracted to intervene in the cluster of eight favelas located in Jacarepaguá, West Zone. She suggests that the firm’s contract was abruptly cancelled because the City realized its political miscalculation in deciding to upgrade these favelas near the future Olympic site. It would be easier to cut the contract and remove these invisible communities “silently and disconnectedly,” instead of with the Morar Carioca spotlight and the program’s stringent resettlement guidelines.

Cavalcanti asserts that Morar Carioca was not—as several critics have suggested—a guise to legitimize evictions. Instead, she argues that housing removals ended up being more urgent to the Olympic project than participatory upgrading.

“There is no time left for social diagnostic. Now [in 2014] they just have to get those people out of there really fast and Morar Carioca gets in the way of their urban planning needs because it was so well-designed.”

Architects and urban planners maintain their inspiring vision for Morar Carioca: a program that expands upon Favela-Bairro by emphasizing a participation methodology, consistent and equitable service provision, and long-term maintenance of projects. Veríssimo described the original Morar Carioca program as a “revolutionary” model that would have transformed the city.

“This is a vision we cultivated for a time, but the reality shows it wasn’t possible,” he said.

Mr. da Luz Moreira affirmed that the idea behind Morar Carioca continues, even though the program itself was “emptied,” concluding: “We are not finding the effective political will to implement [these projects].”

Demanding “FIFA quality” housing

The dismantling of the Morar Carioca program provides us with a critical reflection on the “legacy” framework frequently used to legitimize event-staging. The juxtaposition between Morar Carioca’s visionary model and its failed implementation provide an important example for urban leaders considering the Olympics as a catalyst for development initiatives. It provides a clear example of what Hayes and Karamichas have described as “the seemingly ever-increasing disconnect between [mega-events’] top-down, elite, nature and the ostensible redistributive and participatory agendas staked out by their governance regimes.”

Many of the tensions inherent to the “legacy” framework were evident before Morar Carioca’s failed implementation. The geographic priorities of the IOC would inevitably have confronted the wide-sweeping vision of local urban planners. The temporal constraints of the 2016 deadline and the aesthetic requirements of the Olympic project were certain to override the slow pace of community participation and prosaic demands such as sewage systems. Additionally, the entrepreneurial strategies followed by leaders to become a “global city” are not cohesive with placing favela upgrading in an international spotlight. And the goals of political elites are tied up with private interests that are incompatible with redistributive projects and principles.

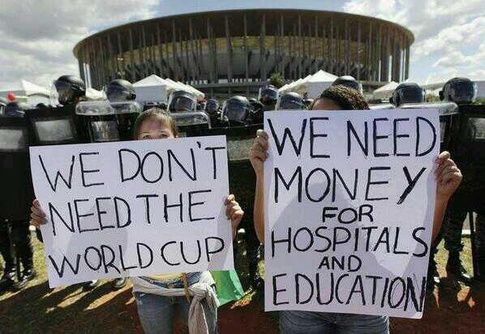

In June of 2013, protesters took to the streets to demand the right to the city. They called for participatory processes and democratic management in a city increasingly being sold to real estate interests behind closed doors. They expressed anger at the “society of the spectacle” when demanding “FIFA quality” public services, such as health, education, and transportation. Finally, many protesters articulated the right to dignified housing and an end to the practice of forced removals in the name of sporting events.

The tensions inherent to the Morar Carioca program—coupled with the reality of its failed implementation—speak to many of these themes. In this moment of accelerated urban transformation in Rio de Janeiro—in which the rhetoric of “legacy” will be wielded to justify a series of exclusionary projects—it is time to demand that Morar Carioca return to the negotiating table.

Kate Steiker-Ginzberg began researching the Morar Carioca program for her 2012 undergraduate thesis at Columbia University. Since then she has been living in Rio de Janeiro and continued research and writing about the impact of mega-events in the city.