For the original article in Portuguese by Henrique Coelho published in G1, click here.

One of the access ways to Complexo do Alemão, in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, has been home to nearly two thousand people for the past seven months. They live in a climate of uncertainty, following a judicial decision that called for the repossession of the old factory where they have been living. Public security authorities in the area confirmed they are planning an operation to carry out the repossession, but as of Tuesday September 9, there was no set date.

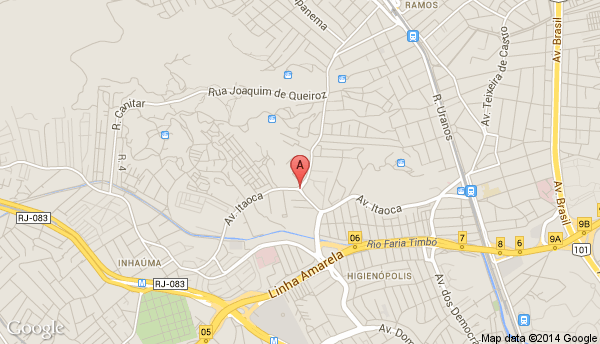

The property is located on 1776 Itaoca Avenue, in the old factory of Arab businessman Tuffy Habib. It houses 1,992 registered people, but the number may be as high as five thousand according to the residents association of Nova Tuffy, as the place is called. The repossession was agreed upon by the 7th Civil Jurisdiction of Méier on March 31 but it still has not occurred because Rio’s court of justice has not decided on a date.

Judge André Fernandes Arruda accepted the request for repossession, brought forth by Tuffy Habib S. A. Business and Industry and the Itaoca Recreational Charitable Association. To accomplish this, however, official letters were sent to the Municipal and State Secretaries of Housing, the Municipal Secretary of Social Development, and the State Secretary of Human Rights; to the command of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) of Nova Brasília; to the municipal and state offices of the Judicial Magistrate and to the State of Rio de Janeiro Public Defenders office to oversee the action and offer support to occupiers.

In the text of the judicial decision, Arruda affirms these cautions were taken “due to the peculiarities of the case, the large number of persons involved in the invasion, and of the recent history of conflicts in the region.” The judge continues to say that despite understanding the acts of the culprits, the housing deficit in Rio “cannot be used to justify invasions and trespassing on private property.” According to the magistrate, there have been several meetings to strategize the operation and the authorization of the Military Police is expected “so that the operation occurs with the greatest amount of security possible.”

At a standstill

While the repossession is on hold, occupiers wait for the end of the deadlock in precarious conditions. The factory, in a worn down location which hasn’t been maintained in at least 10 years according to residents of the area, was invaded on March 23 and was taken over with shacks made of wooden planks with plastic tarps being used as a ceiling on rainy days. Residents, who survive on little potable water and without basic sanitation, say they will not retreat.

“We have to resist. We have all experienced suffering; we are fighters. We want a place to live. A place like this is a disgrace. We won’t leave without a solution,” said Sueli Edith de Souza, 52, who came to the occupation after being unable to pay rent of R$350 (US$250) in Favela da Grota, in Complexo do Alemão.

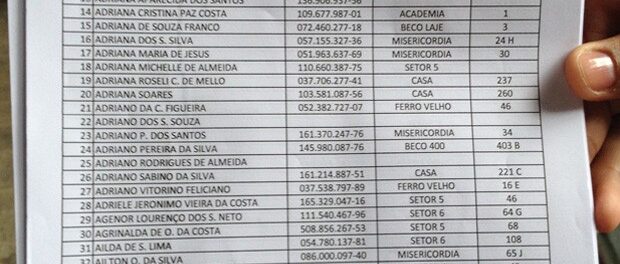

“We are not here to cause a commotion, nor do we want to be used. We just want a solution to our housing situation, we don’t care who brings it about,” said Carlos Alberto da Conceição, 30, appliance assembler and president of the Residents Association of Nova Tuffy. “This is already a de facto community. They will have to be very careful here if they really come to repossess this place,” says the leader, showing the list of residents, recently updated.

According to him, Ícaro Moreno Júnior, the director of the Public Works Company (EMOP), came to the factory and promised that when he returned it would be to register the residents to move to another region. “Never again did he get in contact with us. We want a solution,” he said.

In a statement to the press, EMOP advised that Ícaro inspected the occupied area and that the company is accomplishing many urban reform interventions in many communities through the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), among them the community of Alemão, where the invaded area is located.

During the inspection, Ícaro Moreno told occupants that registration would be necessary so that the socio-economic situation of each family could be verified.

Contact was made with the Secretary of Rio’s City government. According to EMOP, this occurred because Caixa Econômica and the Ministry of Cities, the most important agencies of the federal program Minha Casa Minha Vida, demand that each family be previously included in the Ministry of Social Development and Fight Against Hunger Registry (Cadastro Único). The Reference Center for Social Assistance (CRAS) is responsible for this. The process, according to EMOP, is underway.

Fear and lack of sanitation

Camila Lourenço da Silva, 25, was living free of charge at her mother-in-law’s house in Alemão. She stopped working at 20, when she had her first son, Lucas. Since then, she has been caring for her two children, as her son, Arthur, was born four months ago. Currently, Camila supports herself with the R$400 (US$170) she gets from the federal program Bolsa Família.

The violent images of the repossession of the Oi building in Engenho Novo, in the North Zone, in April are alive in the minds and eyes of these residents, who don’t want the scene—burned buses, vandalized police cars, injured people, and 26 detainees—to repeat itself. When questioned about possible violent action, Camila hugs her first born tighter while he breastfeeds.

“God help me. There are many children here. Have you ever imagined what would happen here if there were pepper spray, rubber bullets? I hope this doesn’t happen,” she says. Today she lives in a room on the top floor of the factory, in the space of little more than 10 square meters.

Occupants complain that, due to the filth and lack of drainage, animals like rats and cockroaches appear with frequency in the homes. Rosimeri Duarte, 46, lives in a shack a little past the entrance of the factory. Despite the limited space, she lives there with her daughter, Fabiana, 5, and says she has already had to take her to the First Aid Unit (UPA) of the region on Itararé Street, due to contamination from the water that arrives at the occupation through clandestine pipe connections. “She had diarrhea, upset stomach, and was really sick. I bought a filter and today she only drinks filtered water.”

The presence of children in the occupation is shocking. Joyce dos Santos Silva, 25, has three children: Juan Vitor, 6, Kariny Victória, 4, and Felipe Ricardo, 1 year and 6 months. She left nearby Jacarezinho, where she lived with a friend, and has lived in the occupation since May. “No one is here because they want to be. I am here because I don’t have anywhere to go with my three children,” she said.

There is also space for single people. Neuza Monteiro Cardozo, 72, lives alone in a shack in the depths of the occupation, in a dark and stuffy environment. She survives by taking care of children and doing housework, and says she needs to earn money to give presents to her grandchildren. “Just counting grandchildren, I have 12. And now one great-grandson who was born one month ago. I spend nearly the entire day outside and I come back at night,” she said.

Day of the occupation

Júnior, one of the leaders of the Residents’ Association, says that on the day of their arrival, 40 to 50 occupying families settled the building and removed two men who watched over the establishment. According to the vice-president of the association, these two maintained it at the cost of residents and businesspeople of the region.

“They were charging R$150 (US$64) for each car kept here, charging R$250 (US$107) for each business owner from this section of Itaoca Avenue. We removed them from here, and they left by motorcycle, shooting up in the air, and the police did nothing,” said Júnior.

An employee of a gas station in front of the occupation who didn’t wish to be identified confirmed that two men left the site shooting bullets into the air. “They left on motorcycles; it was a huge commotion,” he said.

Incidents

Alemão has had a Pacifying Police Unit since 2010. According to the UPP press office, on the day of the families’ entrance, there was record of a shootout in the area and also robbery of objects from inside the factory.

On April 10 occupiers of the factory initiated a protest on Itaoca Avenue and closed the street at the intersection of Itararé Street. According to the UPP press office, protesters were agitated and a police officer was hit in the head by a rock, thrown by a protester. According to the press office, they demanded a solution to the situation of lack of housing in the region.

Residents also experience problems when there are shootouts in the area, which has been common in the past months. “When there are conflicts, we can only pray that nothing happens. Fortunately, nothing has happened,” said Vera Lúcia Pereira, 58, who has been at the site since June. “Rent of R$300 (US$130) became really expensive for me. I had to choose between eating and paying rent. So, I came here,” she told G1.

Answers

In a statement to the press, the State Secretary of Housing said that on April 1 of this year it received an official letter from the Judiciary Power informing the deferment of the preliminary injunction of repossession of the area. By means of this official letter, it was determined that two employees of the Institute of Land and Cartography of the State of Rio de Janeiro (ITERJ), affiliated organ of the Secretary of Housing, were to oversee the action together with other government organs.

Coordination of the Pacifying Police (CPP) was notified about the decision and a plan of action is being elaborated to carry out the repossession, although without a set date.

The other entities cited in the decision already received official letters referring to the case, but they have not responded to the G1 report about how the repossession will proceed.