Ostentation: Pretentious and vulgar display, especially of wealth and luxury, intended to impress or attract notice.

Art, it is said, is the mirror of society. Throughout history, music has reflected, illustrated and influenced social practices. What can the music of funk ostentação, or “ostentatious funk,” tell us about today’s Brazilian society? At the other end of the spectrum of social activity, politicians too display a similar tendency of ostentation. Discourses and projects take on a more symbolic rather than rational function in such a context.

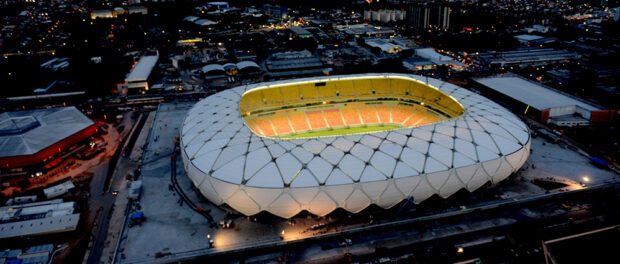

In the opening ceremony of the 2014 World Cup Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff said:

“Now we have modern and comfortable stadiums, from North to South of the country, to match our soccer and our soccer fans. Besides their function for soccer, they will be multi-use stadiums: they will work as commercial centers, business centers and leisure centers as well and will host musical performances and popular parties.”

After having insisted to FIFA that Brazil would host the Cup in 12 stadiums, rather than the recommended 8, this speech and the massive US$16-20 billion ultimately spent on the Cup (more than the previous four World Cups combined), demonstrates a necessity to present Brazil as having achieved a certain level of socio-economic development, and to show this off to the world. MC Guime, one of the biggest names in funk ostentação today, expresses the same sentiment in his song “Plaques de 100“:

“Counting mounds of $100 notes inside a Citroen

Then we invite the girls, because we know they’ll come

For transport, we are doing fine, riding a Hornet or a 1100

We have Kawasaky and Bandit, RR as well.”

Ostentation in music, life and politics

The strategy of conveying power through ostentation is not new or exclusive of Brazilian culture. It has historically represented a way of life by the elite, particularly in a country marked, until just over a decade ago, by the world’s most severe inequality. A country that until the 1880s practiced slavery, having imported the largest number of slaves of any nation in history. Today ostentation also represents a way of doing politics. In the era of excessive media coverage, high profile projects are one of the keys to political success.

Rio de Janeiro suffers from a significant deficit in infrastructure in the sectors of transportation, housing, education, health care and basic sanitation. Yet over the past five years large-scale investments have taken place instead in order to meet promises made to the IOC in order to host the 2016 Olympic Games.

The funkeiro tribe (people who produce, listen to and enjoy Brazilian funk) has built a lifestyle based around the Carioca funk musical genre–a unique blend of rap, tamborzão (big drums), and bass. The genre originated in Rio–as its name indicates–and has reached all regions of Brazil with its beats and lyrics ranging from the politically conscious to sexual to violent. As it was appropriated by São Paulo’s favelas, a subgenre emerged: funk ostentação, known for its ostentatious lyrics and videoclips with explicit references to money, women, cars and material goods that signify financial and social success.

Ostentation is used as a pathway to success by political leaders and favela residents alike: people at opposing ends of Brazil’s social and economic spectrum. So what is the link between them?

Mega-events: showing off to the world

The act of hosting a mega-event is in itself an act of ostentation, due to the enormous investments and elaborate structures erected in association with such events. The hope is that through successfully carrying out such an event, the nation be seen by the world as a safe, modern, confident and wealthy country, while simultaneously convincing its own citizens that the country is entering a small circle of developed, influential nations. The 2008 Beijing Olympics consecrated China’s position as an international superpower. It is hoped by political leaders that the success of major events in Brazil will finally establish the South American giant as a globally influential country.

The international media has played into the game of ostentation politics. Initially doubting the government’s ability to host a successful 2014 World Cup, the international press celebrated the eventual delivery of the event. In the meantime, police repression and comparatively low media coverage meant those who would rather improved public health and education than expensive mega-events were not heard.

The current, ostentatious transformation of Rio de Janeiro has had extreme negative impacts on the lives of many favela residents and on its history and popular culture. Policies include mass forced evictions, military occupation of favelas, psychological and physical intimidation of residents who do not want to move from their homes or who speak to the press, and the creation of high profile transportation systems that raise many questions as to their usefulness for residents. The cable car in Complexo do Alemão, for example, was supposedly built to make residents’ lives easier. However, since its opening in 2010, it has not yet reached full capacity (it runs at around 50%), its pricing is considered prohibitive, and closures are frequent due to maintenance, weather conditions and shootings. Residents are suing the government because they had voted on sanitation improvements, not a cable car, and participatory decision-making was not respected.

In politics and in the favelas

MC Koringa is one of the leading figures of funk since his 2005 hit “Pedala Robinho” went viral. He is also the first funk artist to be played in a telenovela. He perceives a causality link between ostentation in politics and in the favelas:

“There is a cable car, but waste collection is deficient. The schools are not always open, so you produce ignorance. Transportation systems are political make-up. From slaveships to the metro today, it is the same thing. The important thing is getting there. Instead of putting up a cable car on a hill, you need to solve the problems down on the ground. What good is a cable car if you don’t have the security to use it?

“Ostentation [in the favelas] is the mirror of these failures of the government (…) A kid in the favela wants to be bourgeois with his golden chain. Inside the community he may be someone because of it, but outside, he is still no one. This blurs the focus of this young person, he ends up tricking himself.”

Ostentation is part of the dream because even the emphasis of public policies is on the superficial, rather than real welfare improvements. MC Koringa feels funkeiros have a part to play in this: “When the character Koringa plays in Globo’s novelas, he wants to stir that kid that is surrounded by criminals, that is surrounded by drugs. He does not need to live through this cycle…The artist’s responsibility is huge, and I have a lot of respect for that.”

Ostentation as displaying social progress

In a self-produced documentary, funkeiros from São Paulo explained what they think ostentação is all about. MC Boy do Charmes told of his vision: “Ostentation is the funk that talks about a dream that a worker, a father has to get his son in whichever car, on whichever motorcycle, ensure the best condition for his family, the best house, the best flat, in order to give his son a better condition than his.”

In this context, ostentação is about showing that you can provide. It is about demonstrating that you can climb the social ladder, be someone who matters and be accepted in more economically privileged circles.

Brazil’s obsession with ostentation is not divided by class. Professor Clovis Gruner, lecturer in arts, memory and narrative, describes Brazilian shopping malls as the new place in which to express social progression through consumption by the middle class. The rolezinhos—a trend of low-income youngsters organizing group strolls through shopping malls–were repressed by mall security staff and police, and sparked a major debate on accessibility and discrimination in those venues.

Gruner explains: “The middle class has trouble accepting that two of its most central signs of social distinction–consumption and ostentation–are not exclusive privileges, now enjoyed by young people from the periphery who recognize themselves [in that environment], to the point that they made it the soundtrack of their lives: funk ostentação.”

Funkeiro MC Bio G3 says it all has to do with the growth of the middle class: “With such economic ascent, and São Paulo being the luxury metropolis, I think the marginal peripheries wanted to show they could [be successful]. Now I can have R$1000 (US$420) sneakers; now I can have a big, stylish watch; now I can have a R$300 (US$126) shirt, even if it is an effort to own things. But this isn’t limited to funk, everyone got into this general climate. I think funk was able to catch the wave that was passing by.”

Anthropologist Roberto DaMatta wrote in his 1979 book Carnivals, Rogues and Heroes: An Interpretation of the Brazilian Dilemma that social determinism is very present in the Brazilian ethos, but it is counterbalanced by an inclusive mythology (such as the malandro rogue or the masks of carnival). His analysis shines light on “a social structure where the social classes communicate by means of interwoven relations that end up partially inhibiting the conflicts and the system of social and political differentiation based on its economic dimension.”

Ostentação stems from a self-feeding celebration of the new possibilities offered by economic prosperity in Brazil. The urban peripheries, the growing middle-class and the political class have all enjoyed a period of economic progress. Over the past decade individuals felt the tangible effects of a steadily growing economy.

Today, however, economic growth has stalled. The prolonged wait for basic health and education infrastructure illicits the general feeling that appearances matter more than effective progress for the less privileged. Following the election of new leaders on both the federal and state levels this month, the question over whether ostentation is a desirable route to long term prosperity or an expensive façade remains.