For the original by Michel Silva in Portuguese, published in Fala Roça, click here.

Access to clean water and sanitation is an essential human right, acknowledged most recently and thoroughly in a United Nations Resolution in 2010. In Rocinha, you’d be mistaken if you thought the lack of water services in the favela was only a recent problem. The fight for this human right grew in the late 1970s, when CEDAE (the state water utility responsible for providing access to water and sewerage) provided the workforce to supply water to the favela, with material local residents raised money together to buy. It was around this time that Rocinha residents founded the Organizing Committee of the Bairro Barcellos neighborhood.

Seu Martins, a long-time community activist, remembers: “One of the key people was Edson Martinho because, when we took up the task of collecting money from residents to buy the material we needed, I made a public promise that I would make sure the money was returned within three months. Three months went by and we hadn’t even raised 5% of what we needed. I held a meeting at the Catholic Church with the help of ex-Jesuit priest Cristiano Camerman and proposed we give all the money back to the people, but Edson encouraged me not to and said we should ask those who had already paid if they wanted to loan some money to get us started.”

Before the creation of the União Pró Melhoramento dos Moradores da Rocinha (Resident Union for the Betterment of Rocinha–UPMMR), the interests of Rocinha residents were represented by a select few people, along with the Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro and the social organization Ação Social Padre Anchieta. The fight for water supply and sanitation continues today and is still supported by local residents, among them Seu Martins and Chica da Rocinha. Both of them have been fighting for water rights since the 1980s.

Francisca Oliveira, better known as Chica da Rocinha, has been living in Rocinha for 47 years and is an icon in the fight for water in the community. After living in two different neighborhoods of Rocinha–Roupa Suja and Rua 4–she had to move to a larger house in the neighborhood of Cachopa to meet the needs of her children.

To her surprise, her new house was not supplied with water. “I moved to Cachopa in 1992. On the first day in my new house I saw there was no water to make tea or for washing hands. A neighbor gave me a bucket of water. I gave my newly-refurbished house a wipe-down and it was then that I started my fight for water. I went around knocking on my neighbors’ doors, inviting them to meet to discuss the situation in meetings held on the street,” she remembers.

Towards the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, Rocinha became one of the beneficiaries of the public water and sanitation program, Pró Sanear, which aimed to bring basic sanitation to low-income areas. The project was run by then governor of Rio, Leonel Brizola, and funded by the World Bank. The role of managing the program fell to CEDAE, the utility responsible for the collection, treatment, delivery and distribution of water and sewerage in the whole of Rio de Janeiro State. But it was only later, during the mandate of governor Marcello Alencar (1995-1999) that the Pró Sanear program came to be implemented in the favelas.

In an interview with the Engineering Club (Clube de Engenharia) professional association of engineers, Stelberto Soares, a former CEDAE official who worked on sanitation projects in Rocinha, said that the brains behind the Pró Sanear project were not familiar with the favela. He explained that when he began working on the project of bringing water services to Rocinha, the bidding process for the contract to implement the program had already taken place and the winning company had calculated the cost of the works at US$5.6 million.

“When I looked at the spreadsheet my question was: how do you propose to install water services with water pipes going from Gávea [a wealthy neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro’s South Zone] to Rocinha without factoring in the cost of removing and replacing the concrete on the streets of Gávea?” he complained. A short time later the budget rose to US$24.9 million. The problem of the lack of a sewerage network in Rocinha still hadn’t been solved.

In 2004, under the watch of community leader William de Oliveira, the size of the workforce at the CEDAE office in Rocinha grew. “At the time, under the mandate of governor Garotinho, about 60 employees were sent to work in the favela. This allowed us to renew the piping in the Roupa Suja neighborhood,” said William. In his opinion, the big issue is not the lack of water in itself. “The problem with Rocinha is one of distribution. It’s to do with the equipment that brings the water to the community. Other neighborhoods situated close to Rocinha, like Ipanema and Leblon, don’t suffer from irregular distribution of water,” he explained.

From 2008 to 2009, after the launch of the first wave of the federal government’s Growth Acceleration Program, or PAC-1–which included many promises to improve sanitation in Rocinha–the government carried out a household census. The survey found that 90% of households had access to the favela’s basic water supply. Despite this positive statistic, only 21% of households were recorded as having access to water connected to their houses: that is, water being piped into at least one room in the house. One of the problems concerning the poor distribution of water in the community is linked to the population increase, which has not been accompanied by an adequate expansion of infrastructure, including that of a sewerage network. According to José Ricardo, the president of the Neighborhood Association in the Rocinha neighborhoods of Laboriaux and Vila Cruzado, the way water is distributed in Rocinha is outdated.

“At the moment there’s a water pumping station in the Rua 1 district and another deactivated one in the Laboriaux district. If the Laboriaux station was put back in use and other new ones were built, water would be distributed much more easily, with the help of gravity.” In his view, this would also solve the problems concerning water distribution on the extreme edges of the community.

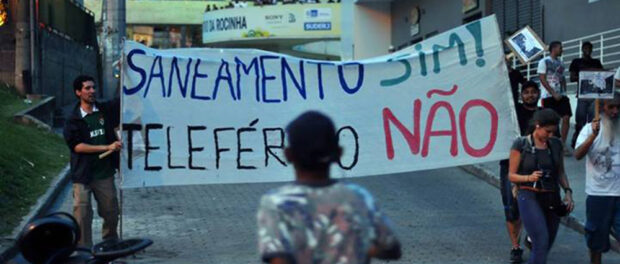

Using funding from the second phase of the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC-2), the Rio state government has announced it will construct a cable car system in Rocinha. The cost of building the system has been valued at around R$1.6 billion (US$600 million); it is a federal government investment that has divided opinion amongst Rocinha residents.

“The PAC-2 construction works for the creation of the cable car system are incompatible with the community’s need for basic sanitation, which residents have been calling for since the 1940s,” says José Ricardo.

In March of this year, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Luiz Fernando Pezão, made a visit to the Vila Verde neighborhood in Rocinha to re-launch an artificial playing field there. Residents used the occasion to call for improvements to the water supply in the community. In a video published by the community media organization Viva Rocinha on YouTube, Pezão states that Rocinha’s water supply problems will be resolved within 30 to 40 days.

According to CEDAE, Rocinha received two new water pipes to improve the water supply in the community in 2014. In a press release, the company announced the following: “In April, CEDAE carried out two important construction works in Rocinha that allowed the company to put two new water pumping stations in operation, increasing the supply of water to the community.” The company stated that the region’s water supply is functioning well. Residents wishing to report problems with the water supply were asked to contact the CEDAE office in Rua 1, Rocinha. “We ask that they inform us of the address so that technicians can be sent to investigate the supply and look for obstructions or leaks in the pipes. The company has an office that operates full-time in Rocinha, which residents are welcome to contact in the case of a lack of water or a leakage,” they said in a note.

It is important to remind residents, however, to use water in a conscientious way and avoid wastage, in order not to weaken their argument when claiming for adequate basic sanitation.

FALA ROÇA is a print newspaper, run by Rocinha residents, founded in 2012 with support from the Networks for Youth Agency (Agência de Redes para Juventude). It focuses on northeastern culture within Rocinha, one of the largest favelas in Latin America.