For the original in Portuguese by Miriane Peregrino, published in Agência de Notícias das Favelas, click here.

The Santa Marta tram was launched on May 29, 2008, the same year Rio de Janeiro’s first Police Pacification Unit (UPP) was established in the same community on December 19. It was a funicular tram up one of the steepest favelas of the city, which for several years thereafter became known as the ‘Model Favela’ with a UPP. Two years later, the project Rio Top Tour was launched in Santa Marta, as a partnership between the Ministry of Tourism and the city government. Santa Marta was founded between the 1920s and 30s, with an area of 53,706m² and around 4,000 residents.

“Rio de Janeiro, Botafogo, South Zone,

Community of Santa Marta

73 years of resistance, my partners.

Go up, go down. Go down, go up,

Every day. Can you believe…

788 to get up there to the top

788, you have to have faith in Christ

788 to get home

788 is the truth of Santa Marta!

…Today it’s got a tram, but it can’t deceive me

Uh, babou … I have to go up on foot.”

– 788 by Repper Fiell from the album Pedagogia da Dominação (Pedagogy of Domination) (2013)

1. The tram

I met Dona Maria de Lourdes, aged 57, at the bottom of the Santa Marta steps. I asked her where the Residents’ Association was and she readily told me: “I’m going up to station four. Come with me, I’ll take you there.” Having already gone up to the top once, I found this strange. There are 788 steps to the top of Santa Marta which is at station five, so to get to station four she would be going up at least 500 steps. I asked why she didn’t go up in the tram. Dona Maria shrugged her shoulders, put her shopping bags down on the ground, gave a light smile and replied: “The tram isn’t working today, so by foot it is.”

At that moment a mailman (he preferred to remain anonymous) walked by. “When the tram is working I go up on it but when it isn’t, I go by foot. Today, it’s not working so it’s got to be by foot.”

Resident Cosme Uchôa, 59 years old, also complained about the malfunctioning tram and added that it’s a problem the company needs to fix. He said: “There are people who work and go to great lengths to make sure things work. Julian, for example, he’s a resident and works there. But he has to buy parts for the tram, a lot of things need changing. The company needs to do this. The Prefeitura (City Hall) needs to see.”

“As always it’s out of service,” Dona Maria de Lourdes said. “I climb slowly. There are people who use crutches. There are people who never leave the house because the tram is faulty.”

The tram is free and makes the journey through five stations up to the top of the hill. When questioned about the last time it was working, the resident recalled, “On Saturday.”

2. Tourism

While the malfunctioning of the funicular tram is inconvenient for residents, it does not seem to stop the increasing influx of tourism in Santa Marta. According to José Elias, resident and local guide, 80% of the tourists he receives in Santa Marta are foreigners.

“The demand for Santa Marta is huge; it’s the favela that is truly pacified. We have a flow of around two thousand people a month,” he said.

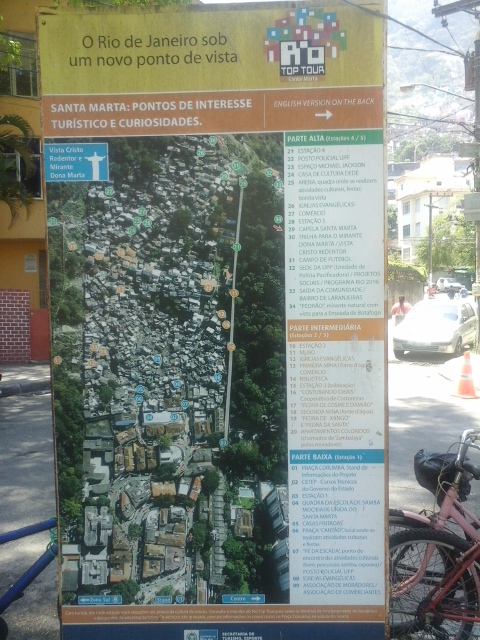

The Rio Top Tour project consists of at least 34 local tourist points in Santa Marta, including the trail to the Dona Marta observatory with a view of Christ the Redeemer, evangelical churches and chapels, the “Pedrão” observatory, and the Michael Jackson terrace.

José Mário, president of the Residents’ Association and the Community Union agreed with tour guide José Elias that the most visited tourist point of the favela is the Michael Jackson statue at tram station four. The bronze statue was launched in Santa Marta in 2010, a year after the death of the singer. Its location was named Michael Jackson Terrace by the State Government and it commemorates the pop star’s visit to the favela to shoot the video for the song “They Don’t Care About Us” in 1996.

Questioned about tourism in Santa Marta, José Mário pointed out both positive and negative aspects.

“We receive around 10,000 tourists, 3,000 of them foreign, per month. The positive is that it creates an expectation among the community, it improves business, people are interested in speaking other languages: English, Spanish, French. There is that positive side of it but the negative is that the community feels like an attraction park where people come here and see the community like animals at a zoo. They come, walk around, look at people and then leave. That’s the negative side, I think.”

Favela resident Mr. Ronaldo, 60 years old, seemed impressed with the flow of tourists: “There are lots of gringos here. Even early on Saturdays and Sundays they’re already coming down [the hill]. They take photos of the mice, of the dog poop… man! Everything is a novelty for them.” Mr. Ronaldo said life in the favela “has improved, but to be a model favela there’s a long way to go…”

For resident Cosme Uchôa, Santa Marta still needs to improve: “The favela community still needs to rethink the hill’s garbage situation. Everything needs rethinking. [The canned paint company] Coral painted some houses here but look at the propaganda for the company. All this is investment, nothing came here for free.”

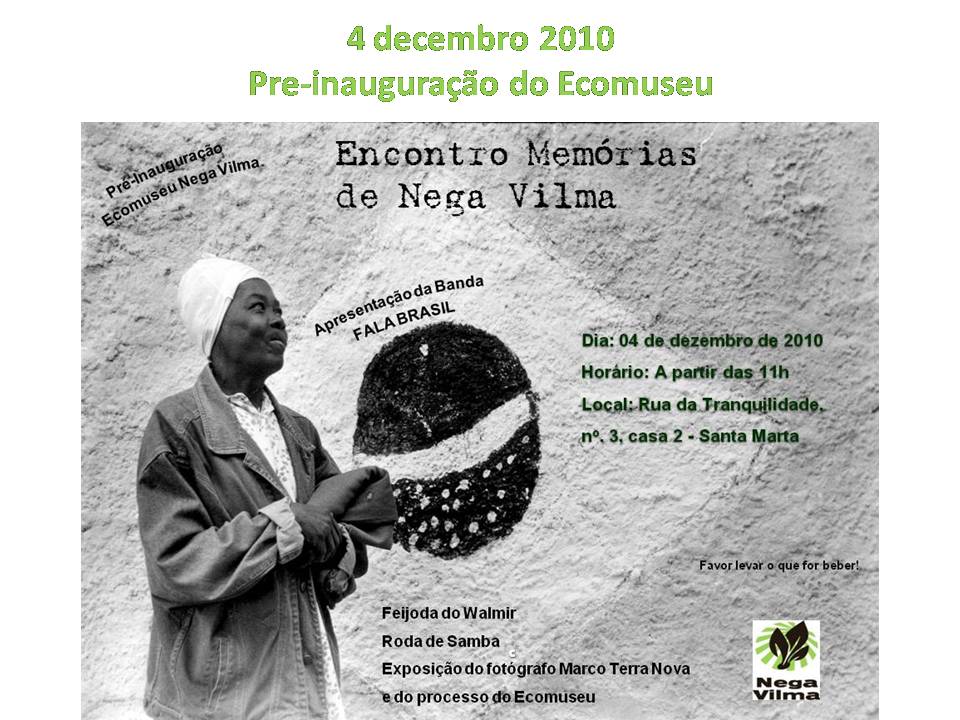

The tourist information stand in Praça Corumbá (at the entrance at the bottom of the hill) highlights one significant favela location which, at least for now, does not make the Rio Top Tour’s list of 34 points of interest: the Nega Vilma Ecomuseum, situated on top of the hill (Rua da Tranquilidade, n. 3, casa 2, Pico do Santa Marta/Botafogo). According to the tour guide the Rio Top Tour team did not know about the Ecomuseum program.

According to Kadão Costa, 38, founder and one of the managers of the Ecomuseum, Nega Vilma was left off the list of the favela’s tourist points because the list was generated before it was officially registered in 2013. “Furthermore, Santa Marta has a very strong political force and many [other] institutions exist [here],” said Kadão. In regards to visits, Kadão informed me the Ecomuseum is currently being renovated but visits can still be arranged directly with the institution via email or by phone (+55 (21) 988-250-576).

3. The Nega Vilma Ecomuseum

Ecomuseum is the name given to an establishment that is part of a community and helps to develop its territory, not only by valuing its history and local culture but also by respecting its natural environment.

Kadão, whose full name is Ricardo da Silva Costa, is the son of a nephew of the Candomblé (Afro-Brazilian religion’s) priestess Nega Vilma (1943-2006). He explained that his family’s history is told along with the history of Santa Marta and that he believes in an integration of the hill (morro) and the formal city below (asfalto, literally “asphalt”) through culture. He also said that while there are lots of descriptions of Santa Marta, “they reduce the community down to the place that Michael Jackson went.”

“Nega Vilma’s story brings together very present features which symbolize so many other histories in this and in other communities,” he continued. “The relationship between the museum and the community [of Santa Marta] still isn’t ideal. There is a certain resistance because they all think their parents are as or more important than Nega Vilma and should have the Ecomuseum named after them. There is also the fact that people don’t value their space and don’t recognize the value of their daily lives. But this is already changing and today we have a much better relationship [with the community] than when we started.”

In fact, on arriving in Santa Marta, few residents were able to give me any information about the Ecomuseum. It was through formal scheduling that a group of young people from Complexo da Maré came to see the Nega Vilma Ecomuseum last year. One sunny Saturday morning, Raíza Barros, 17 years old, fell ill climbing up the steps through Santa Marta and she only reached the Ecomuseum at the top because she finished the ascent on the tram.

“I confess I found this museum very odd, it’s one room and it’s difficult to get there,” said the teenager. “The other thing I kept thinking about was the number of steps people have to climb, and the tram has only been there for 5 years. It’s so many stairs, I was surprised!”

As if the 788 steps to the top weren’t enough, the ground is pretty rough, and these challenges reflect the routine of daily struggle, not only for Nega Vilma but for all residents of the favela. This is a struggle that is still present to this day, a struggle we saw through Dona Maria de Lourdes, 57, carrying her shopping bags on a recent January afternoon on a day when the tram, yet again, was not working.

Matheus Frazão, 17 years old, called our attention to other aspects of the visit to the Ecomuseum: “We were really well received, we exchanged ideas, we spoke about religion—which plays a really strong role within the communities be they Catholic or Candomblé—and the view from up there is so beautiful.”

Although the Ecomuseum does not have a programed tour, it has some partners on the hill who support its activities, such as the Vanderléia restaurant and Lurdes Ice-creams, where Kadão also takes visitors. “We don’t have a set tour, we have options which depend on the type of visitor we have,” said Kadão. “The Ecomuseum has existed since 2009 and in truth we have existed through donations of Vilma’s family and friends. We don’t have any patrons but we legally exist as a non-profit organization.” The Ecomuseum video is not to be missed.

4. From Santa Marta to other favelas

In the fight against real estate speculation, electric bill increases, a repressive state and other issues, many Santa Marta residents are organizing themselves to put together protests, music, documentaries and books. Although Santa Marta is still not the model favela the government initially promised, the increasing number of foreign residents in the favela is noticeable. Resident Cosme Uchôa, married to a Swede, said: “We have foreign residents here but they prefer Vidigal more, don’t they?”

In 2010, the The Santa Marta People’s Handbook: Addressing the Police was launched as a tool to affirm the rights of residents and strengthen the community. Santa Marta: Two weeks on the hill, a documentary directed by Eduardo Coutinho, is another important reference to understand the development of the favela and state intervention, primarily through the use of police force. Although it dates back to 1987, it highlights aspects that continue today.

Repper Fiell, born in Paraíba and resident of Santa Marta for 9 years, tells his story of struggle in the favela through hip hop and in 2011 he released the book From the Favela to the Favelas: The story and experience of Repper Fiell, in which he recounts his story as a northeastern migrant and resident of the first favela in Rio de Janeiro to have a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP).

He writes: “By the arrival of the Olympics in 2016, I don’t know if we will still be here on the hill of Santa Marta. Today, more than ever, we have a very high cost of living. Our electricity bill comes with unexpected costs…Subtly, they are sanitizing the favela, without all the residents realizing.”

Jeferson Luciano, 17, recognizes the author’s courage in speaking what he thinks, but suggested the rapper “sometimes exaggerates when, for example, he criticizes the people who go to shopping malls to hang out.”

Ferreira stated: “Repper Fiell is close to us favela residents because he knows what the favela is really like, what happens here and that we are not criminals.” Aline Moura, 17, had a similar reaction: “My impression of the book is that he speaks personally to us, he opens our eyes to the injustice, discrimination, poverty, rights that we don’t have, everything that happens daily in our favela called ‘community’ by politicians who like to put make-up on our situation.”