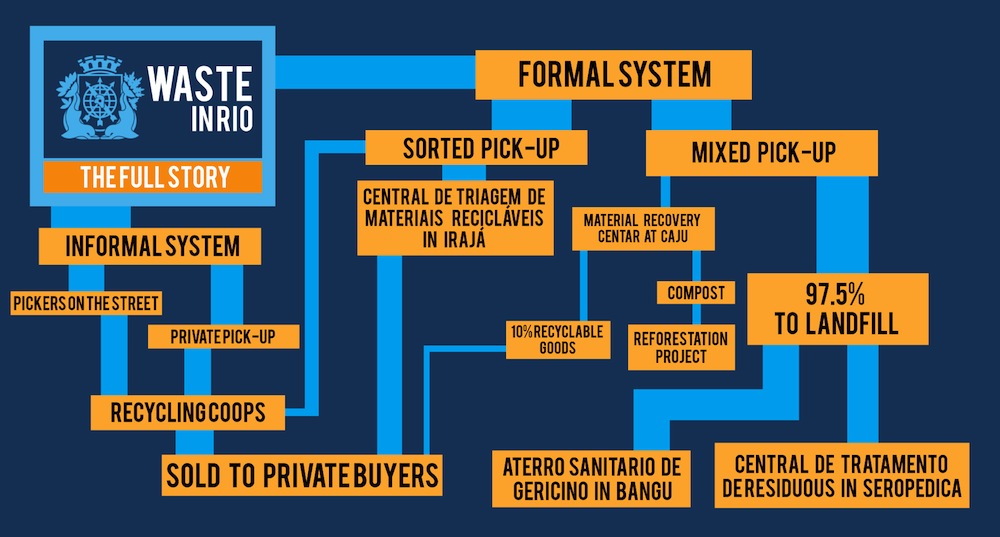

Recycling is an essential element of waste management for any city, and it becomes an increasingly critical issue proportionately to the size of the city and its metropolitan area. Any degree of recycling reduces the amount of waste discarded in the environment. In Rio de Janeiro, that waste often ends up in official landfills or floating in places like Guanabara Bay, which will host the Olympic sailing competition next year and is notoriously polluted. Increasing the capacity for recycling reduces problems associated with waste like disease, pests, and contamination of soil, air, and water. In Rio, the formal recycling system handles a very small percentage of the estimated 10,000 tons of waste collected every day by Comlurb (the city’s Municipal Waste Management Company). The vast majority of recycling happens before Comlurb collects any waste, an informal recycling system that relies on the initiative of both individuals and for-profit companies.

The most familiar feature of the informal world of recycling are catadores, individuals who walk around the city collecting recyclable materials, sifting through trash cans and garbage on the street. They act as members of recycling cooperatives or work independently and sell to such coops. By doing the work that, in other parts of the world, falls on the individual throwing out the item, catadores fill a vital gap in Rio’s recycling system. Their income comes from lugging materials from streets, beaches, and trash cans to buyers of recyclable materials. Cooperatives of varying levels of formality process these materials and play an important role in giving individual recyclers buying power as a group.

Another component of Rio’s informal world of recycling is private pick-up services for condominiums and buildings. Cariocas (Rio natives) living in large condominiums may be familiar with sorting their waste and having separate pick-ups for recyclable goods. Recycling cooperatives or private companies buy the recyclable materials from the condominium and provide the pick-up services. Whatever is then left over is picked up by Comlurb. The for-profit centers sort and assemble the materials into much larger packages. Acting as dealers, these centers then sell the materials by the ton to private companies like the Rio Recycling Center (CRR) and RMJ Recycling Company (RMJ Comercio de Reciclagem).

The formal recycling system handles a much smaller percentage of waste. Recycling in the most traditional sense involves a separate curbside pick-up service for sorted waste. Individuals must separate their waste and place their recyclable materials on the curb on a particular day of the week in a transparent plastic bag. This service is provided to approximately 88 neighborhoods in the city, but due to the small scale of the operation, accounts for only 3.7% of the city’s total waste.

From there, sorted waste goes directly to Comlurb’s most recent installation: the Central de Triagem de Materiais Recicláveis (Recyclable Materials Central Triage, or CT) in Irajá. CT is a cooperative of recyclers that opened with fanfare and corporate sponsorship in January 2014. Although CT has the capacity to process up to 20 tons of waste per day, it operates far below that capacity due to the limited amount of sorted waste picked up daily by Comlurb. The cooperative functions without Comlurb management but with continued corporate sponsorship for compacting machines and a conveyor belt to speed up the sorting process. Approximately 70-80% of the waste is then bundled and sold as recyclable material, with the profit split among the recyclers according to the amount they sorted for the month.

Most waste in Rio, however, goes straight to the landfill, whether recyclable or not. When the documentary Waste Land highlighted the lives of catadores, or waste pickers, in the landfill Jardim Gramacho, the movie put enough pressure on Rio’s mayor to close down the site. Today, two landfills are in operation: Aterro Sanitário de Gericinó in Bangu and the new Central de Tratamento de Resíduos (CTR), in Seropédica, which opened in 2011. Both sites are closed by law to catadores.

Approximately 40 catadores from Jardim Gramacho found new employment at the Material Recovery Center (MRC) at Caju, according to the office manager, João Cláudio Jayme Franca. The MRC opened in 1992 and employs about 120 recyclers who process 250 tons of waste daily. Today the MRC aims to provide a space for recyclers to do the work they did at the landfill sites but within a controlled setting. Because the center deals exclusively with mixed waste, only about 10% of the waste turns out to be recyclable. The site is owned and managed by Comlurb but the recycling center is used by a cooperative of recyclers who are paid based on how much and what kind of material they individually collect. According to information provided by Franca, the cooperative had a profit of US$45,000 (R$130,000) in February of this year. The average worker makes US$330 (R$1000) per month. Similar to other cooperatives, the recyclable materials are packaged and sold, but unique to this site, the remaining mix of organic materials and nonorganic waste goes into compost. After 90 days outdoors, the compost is filtered and then used by the State’s reforestation project.

Since Rio de Janeiro won its bid to host the 2016 Olympic Games, the City has planned significant changes to its waste management system. New recycling centers are scheduled to open in the next year and sorted waste pick-up services have expanded from 42 neighborhoods in 2010 to 88 at the end of 2014. Still, the great majority of recycling happens outside the public system, relying on private cooperatives to fill the gaps in government services. It is argued that since garbage from poorer communities is less likely to include recyclable materials (and more likely to include organic materials), there is little incentive for the private sector to recycle in favelas. In neighborhoods with limited pick-up services or open trash piles it is no surprise materials end up scattered in the surrounding environment or floating in bodies of water.

The rising costs of natural resources has significantly increased the profitability of recycling activity worldwide. In Brazil, collecting, packaging, and selling aluminum cans alone amounted to US$600 million (R$1.8 billion) in economic activity in 2012. Waste management, while unglamorous, is a lucrative industry. Recycled goods are bought and sold and frequently shipped across the world to countries like China to be repurposed. It is important to note that shipping and processing those materials has an impact on the environment as well. The life cycle of a plastic bottle or aluminum can does not end after a consumer conscientiously tracks down and uses a recycling bin. The only way to actually reduce, in real terms, the impact on the environment is to reduce consumption of packaged goods. In Brazil the trend is going in the opposite direction, with sales of bottled water up 20% in 2014, for example, after a decade of steady growth.

Special thanks for help in researching this article to Ramya Ahuja and Sergio Guerreiro Ribeiro of the Waste to Energy Research and Technology Council of Brazil.