This is the first article in a series by researcher Stephanie Reist,* on Rio’s metropolitan region. It is part 1 of 2 articles introducing the Baixada Fluminense. For part 2 on the region’s culture, activism and integration, click here.

Center-periphery dynamics characterize not only Rio’s relationship with its favelas, but also the city’s relationship with the surrounding metropolitan area. Niterói, the city across the Guanabara Bay, is known by some tourists for its numerous buildings designed by famed architect Oscar Nieyemer. However, other cities in Greater Rio like Duque de Caxias, Magé, and Belford Roxo are stigmatized in much the same way as Rio’s favelas: tourists are encouraged to avoid them and some cariocas scoff at the idea of living or even venturing farther north than Maracanã stadium.

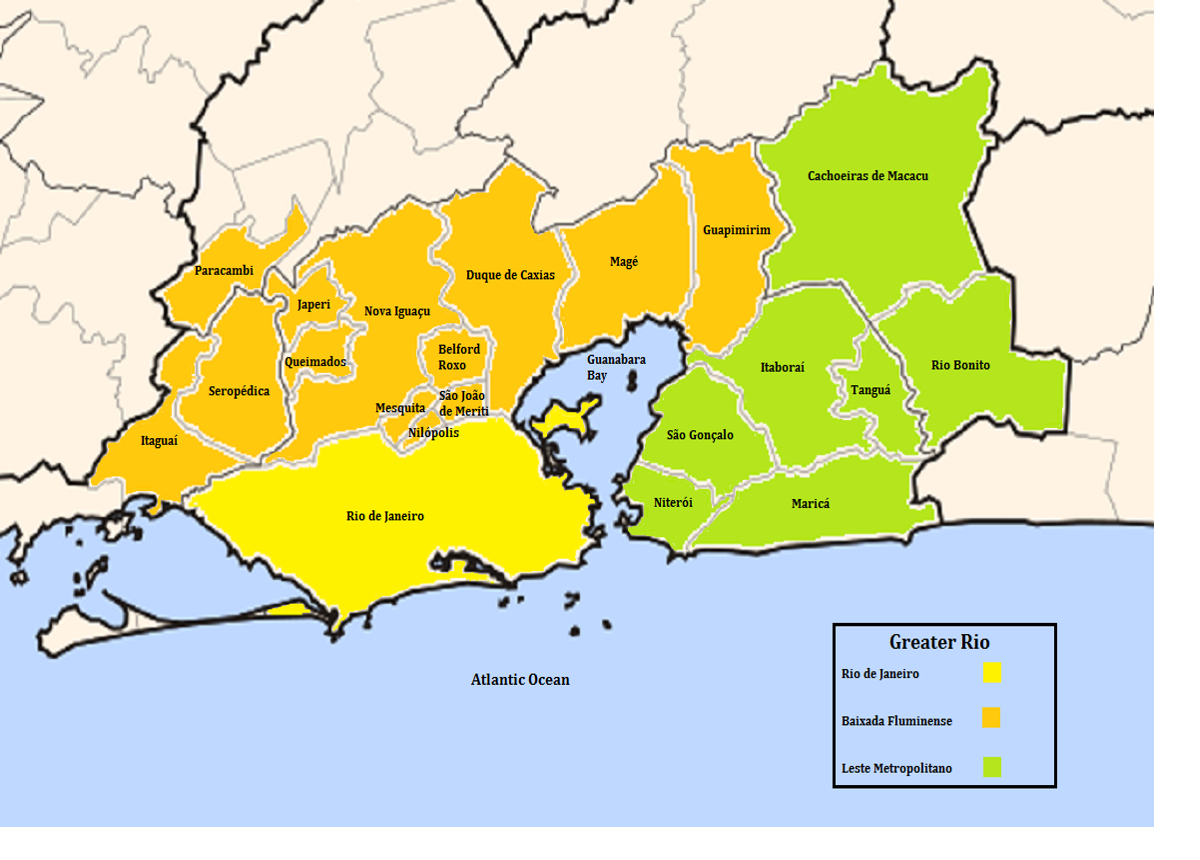

Outside Rio’s city limits, Greater Rio can be divided into two regions: the Leste Metropolitano and the Baixada Fluminense. The Leste Metropolitano (East Metropolitan Region) refers to the east side of the Guanabara Bay and includes the municipalities of Niterói, São Gonçalo, Tanguá, Maricá, Rio Bonito and Cachoeiras de Macacu. The Baixada Fluminense (Rio Lowlands) is north of Rio proper and includes the municipalities of Belford Roxo, Duque de Caxias, Guapimirim, Itaguaí, Japeri, Magé, Mesquita, Nilópolis, Nova Iguaçu, Paracambi, Queimados, São João de Meriti, and Seropédica. Though this article will focus on the Baixada Fluminense (Baixada), many of the issues faced by this region are present throughout Greater Rio.

History

Industry, transportation, and labor flows have defined the link between the Baixada Fluminense and Rio de Janeiro throughout its history. From the 17th through 19th century, enslaved Africans and their descendants toiled in the Baixada’s mountains as Rio’s coffee production came to represent up to 77% of Brazil’s economy. São Paulo’s production only surpassed Rio’s in 1883. In the early 19th century the region became an important railroad hub, connecting the resource-rich state of Minas Gerais with the coffee plantations of the Baixada and Rio de Janeiro’s (then imperial capital) new train station, Central do Brasil (Central Station).

Demographically, the Baixada Fluminense began to grow rapidly in the 1930s following the construction of the Presidente Dutra and Washington Luís highways. Many migrants, particularly from Brazil’s Northeast, also settled along Avenida Brasil. The region’s growth led some districts at the time to break off into their own municipalities: Itaguaí, Magé, and Nova Iguaçu became municipalities in 1939, with Duque de Caxias following in 1944.

Like many of Rio’s favelas, the region was settled with little government planning and investment. People who settled the area had to build their own infrastructure and sewerage systems to deal with the numerous rivers that descend from mountains and empty into the Guanabara Bay, making the region susceptible to flooding and mosquito-borne illnesses including, at the time, malaria. Flooding continues to be a serious issue in the region. In 2013, over 2000 people were displaced by flooding in the Baixada.

Poor public management has characterized much of the Baixada’s history, with governing tactics ranging from propaganda and clientelism to paramilitary intimidation. Director Sergio Rezend’s acclaimed film, “O homen da capa preta” (The Man in the Black Cape), captured the violent political climate of 1950s Baixada through its portrayal of State Senator Tenório Cavalcanti. Known as the “king of the Baixada,” Calvalcanti would carry his machine gun nicknamed “Lurdinha” whenever out in public, and one of his political opponents, Albino Imparato, was found dead. Since the 1960s, many areas have been controlled by militias and ruthless “death squads,” often composed of military police with connections to local politicians.

Socio-Economics of the Baixada

Today the Baixada is home to nearly 3.7 million people. About 300,000 commute from Duque de Caxias, Belford Roxo, or Nova Iguaçu to Rio for work or school. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) refers to the municipalities of the Baixada as “dormitory cities” since they rely so heavily on Rio for employment.

This lack of local employment makes poverty an entrenched problem in the Baixada. Census data show that while only 20.9% of Rio’s population lives on half a monthly minimum wage per capita, 33.7% of Baixada residents do. This level of poverty is similar to that observed in Rio’s favelas, in which 34% of the population lives on half a monthly minimum wage per capita.

The industries that do exist in the Baixada have been criticized for their health and environmental impacts. Plastic and chemical manufacturing dominate the region. Duque de Caxias, the largest city in the Baixada, is home not only to the Gramacho landfill (featured in the movie Wasteland)—which until its closure in 2012 was the largest landfill in Latin America—but also to the Cidade dos Meninos, a neighborhood known for both a large orphanage and a now defunct and neglected state-operated malaria research institute that has been leaching chemicals into the surrounding area for more than half a century.

The geography of the Baixada coupled with negligent public officials has made sanitation an ongoing concern in the region. In terms of sewerage systems, Belford Roxo, Duque de Caxias, and São João de Meriti rank among the ten worst Brazilian municipalities with populations over 300,000. In 2013, when residents met with UN Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation, Catarina de Albuquerque, they claimed public officials intentionally limit water to certain communities, while making it available to companies like Coca-Cola.

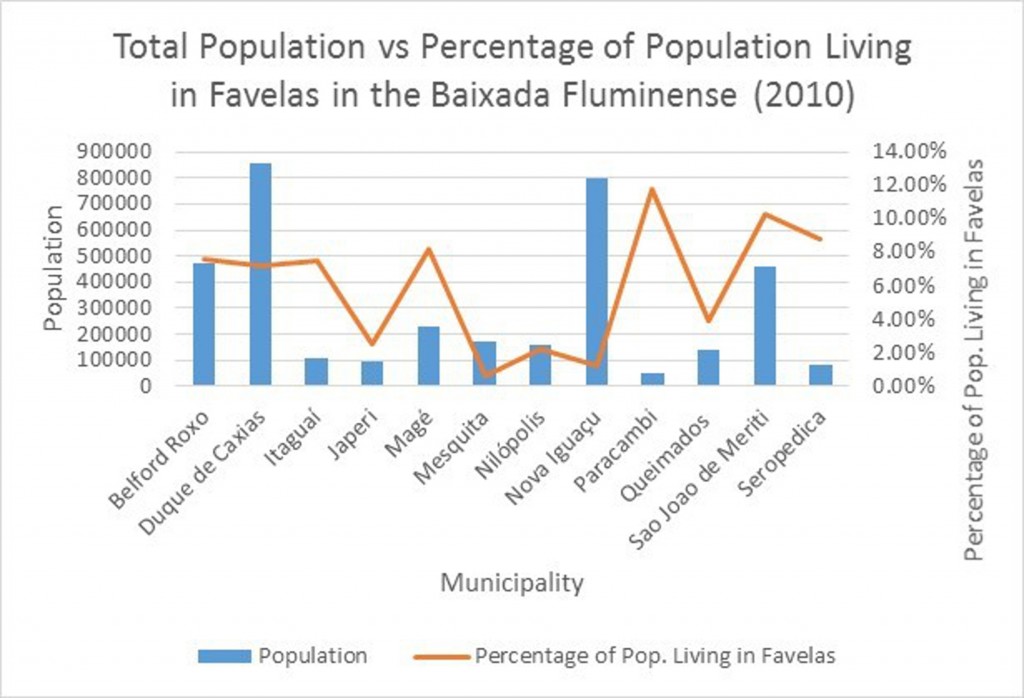

Favelas are also a common feature throughout the Baixada. While many of Rio’s favelas are situated on the mountains surrounding the city, favelas in the Baixada are often in flood-prone lowlands. According to the 2010 census, there are 321 “aglomerados subnormais” (subnormal agglomerations, the term used to designate a ‘favela’) in the region. While the Baixada in general lacks public services, the situation in the region’s favelas is condemnable and significantly worse than Rio’s favelas on average. Garbage collection, sanitation, paved roads, and health services are scarce or nonexistent.

Over 365,000 people live in favelas in the Baixada, representing roughly 5.6% of the region’s total population. This figure is much lower than nearly 22% of Rio proper’s citizens who live in favelas. However, in Belford Roxo (favela pop. 469,332), Duque de Caxias (855,048), Magé (227,322), and Seropédica (78,186), just over 7% of each municipality’s population lives in favelas, while 10% (458,673) of São João de Meriti’s and nearly 12% (47,124) of Paracambi’s populations live in favelas. São João de Meriti has one of the highest population densities in Latin America (13,024 habitants/km2), leading to its nickname: “Anthill of the Americas.”

Complexo da Mangueirinha, a complex of favelas in Duque de Caxias, was the first outside Rio de Janeiro and 37th of the current 38 to be occupied by a Pacifying Police Unit (UPP). Residents and public officials in the Baixada have been critical of the UPP process since its inception in 2008, claiming that UPPs in Rio’s South Zone only served to push crime into peripheries like theirs. However, since parts of the Baixada were already violent before the UPP process began, the data are unclear as to whether the UPPs have made conditions in the Baixada worse. In January of 2014, a month before the UPP arrived in Mangueirinha, Rio de Janeiro State Public Security Secretary, José Mariano Beltrame, announced plans for other UPPs in Greater Rio, likely in São Gonçalo, outside of Niterói.

For part 2 on the region’s culture, activism and integration, click here.

*Stephanie Reist is pursuing both a Masters in Public Policy and a PhD in Latin American Studies at Duke University. In Rio, she has been working as a Felsman Fellow at Projeto Raízes Locais, a community-based project run by Associação Terra dos Homens, in Mangueirinha, Duque de Caxias. Her research looks at center-periphery dynamics, belonging and citizenship, and land rights.