This is the second article in a series by researcher Stephanie Reist,* on Rio’s Metropolitan region. It is part 2 of 2 articles introducing the Baixada Fluminense. For part 1 on the region’s history and economy, click here.

Culture and Activism in the Baixada

The characterization of the Baixada Fluminense as a violent and poverty-ridden periphery fails to recognize the economic, historic, and cultural significance of the region in shaping Rio de Janeiro and Brazil as a whole. Due to the large number of mostly black migrants from Brazil’s Northeast, the Baixada has one of the highest concentrations of Candomblé and Umbanda terreiros, or Afro-Brazilian religious sites, in the State of Rio. Casa-Grande de Mesquita is the continuation of one of the oldest terreiros in the region, and important candomblé priestesses like Mãe Meninazinha de Oxum in São João de Meriti and Mãe Beate de Iemanjá in Nova Iguaçu have been practicing in the Baixada for decades. Famed Afro-Brazilian poet and artist Solano Trindade also called Duque the Caxias home and one of the most successful occupations in the city is named after him.

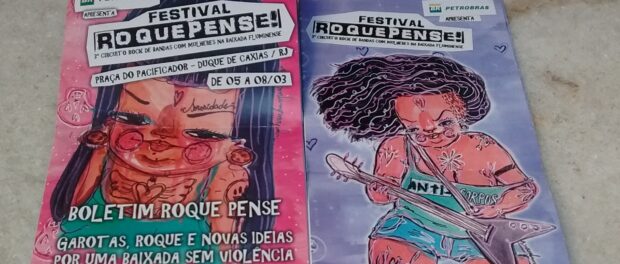

The Baixada is also home to a host of other important cultural producers. The anti-sexism collective Roque Pense! organizes an annual festival of female rock bands that coincides with International Women’s Day in order to combat violence against women. Território Baixada is a series of debates and exhibitions involving cultural producers, activists, and researchers that seeks to integrate and reshape the region.

Many local community leaders and organizations are also working to reshape the image of the Baixada. After one of Rio’s most violent massacres, in which Military Police indiscriminately killed 30 people on the night of March 31, 2005 in Nova Iguaçu and Queimados, the Dioceses of Nova Iguaçu and Duque de Caxias came together with local activists to form Fórum Grita Baixada (Scream Baixada Forum) to denounce violence and monitor human rights abuses in the region. Casa Fluminense, established in 2013, advocates for public policies that contribute to the “strengthening of democracy and sustainable development” in the Baixada and Greater Rio as a whole. The two organizations recently joined forces during the month of April to offer a course on public security taught by local activists and researchers.

Regional Integration: A Path Forward?

Many activists and policymakers see greater regional integration as the path forward in the Baixada Fluminense. In August 2014, Rio de Janeiro State Governor Luis Fernando Pezão signed a decree creating the Metropolitan Council for Governmental Integration (CIG) for the Rio Metropolitan area. Representatives from all 21 municipalities in Greater Rio will come to discuss and advance public policies that impact the entire metropolitan area.

To jumpstart its work, the Council, together with VozeRio and the Institute for the Study of Labor and Society (IETS) held a series of open debates called Rio Metropolitano: Desafios Compartilhados (Metropolitan Rio: Shared Challenges) that invited municipal officials and civil society to discuss regional integration. Four debates were held in four different municipalities in the region: sanitation was discussed on May 5 in Duque de Caxias, transportation on May 11 in Nova Iguaçu, public security in Niterói on May 20, and health on May 28 in São Gonçalo. The series closed on June 1 at the Federation of Industries (FIRJAN) headquarters in the center of Rio.

The push for integration, however, is almost as old as calls for urban reform that take into account Rio’s favelas. Rio has been attempting to integrate the governance of the region since its capital city status was transferred to Brasília in 1960, and more so since 1975 when the state of Guanabara, which previously contained only the capital city of Rio, and the state of Rio de Janeiro, which previously contained all other municipalities in the state with Niterói as its capital, merged together.

Though the transition from national capital and state, to state capital and regional metropolis happened over 40 years ago, Rio de Janeiro continues to struggle with its role as metropolis. Even the planning of mega-events like the Olympics is concentrated in the city, and some argue only in the city’s wealthy South Zone and gated community-modeled Barra da Tijuca, rather than across the metropolitan region as a whole.

For part 1 on the region’s history and economy, click here.

*Stephanie Reist is pursuing both a Masters in Public Policy and a PhD in Latin American Studies at Duke University. In Rio, she has been working as a Felsman Fellow at Projeto Raízes Locais, a community-based project run by Associação Terra dos Homens, in Mangueirinha, Duque de Caxias. Her research looks at center-periphery dynamics, belonging and citizenship, and land rights.