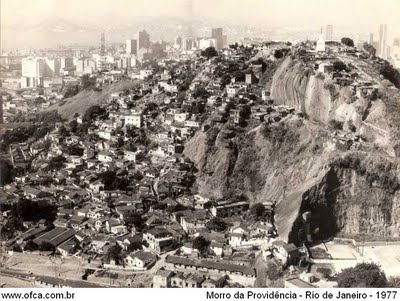

Brazil’s first favela, Morro da Providência (Providence Hill), was built by veterans of the Canudos War. Thousands of soldiers flocked to Rio when the war ended in 1897, because the government had offered them housing in the nation’s capital. Veterans built provisional shelters on the hill while they awaited the promised housing. When it never materialized, the initial settlement grew into a permanent community originally called “Morro da Favela” or “Favela Hill,” named after the shrubby plants soldiers had lived amongst during their battles in the Northeast. Freed slaves and their descendants joined the original settlers, arriving in search for jobs in the city which failed to provide affordable housing. Today Providência, which sits on a hill between Rio’s Port Zone and central thoroughfare Avenida Presidente Vargas, houses 5,500 people. In April 2010 the seventh Police Pacification Unit (UPP) was installed in the community. In 2008 the community gained prominence when it served as the subject and object of an enormous installation by French photographer JR.

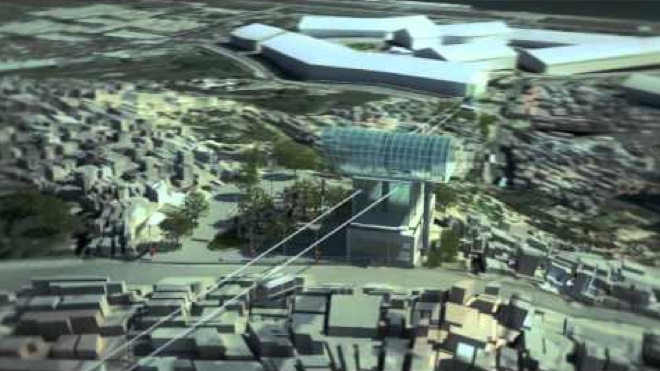

Today Providência is the site of a large-scale urbanization project that will include a gondola, a furnicular tram, streetlights, and housing. The interventions will be carried out under the auspices of Porto Maravilha, a project that aims to revitalize the area surrounding Rio’s port.

Porto Maravilha is a Public-Private-Partnership (PPP): Rio’s government has signed a R$7.6 billion contract with the Porto Novo Consortium, comprised of Norberto Odebrecht, OAS, and Carioca Engenharia. The consortium assumed responsibility for the area in February of this year and the concession lasts fifteen years. These three corporations will receive the resources from a private fund administered by the city-owned Port Urban Development Company. Porto Maravilha seeks to redevelop and revitalize the port area given its proximity to the city center and thus boost the region’s attractiveness to business. Tourism is a key feature and the project aims to create a cultural center, with a new museum, aquarium, and art fair. The three companies will take responsibility for infrastructure upgrades in port neighborhoods, stated to include rerouting a main road through an underground tunnel, improving sidewalks, plazas, sewage systems, water, and drainage.

As part of Porto Maravilha, Providência is the first favela to have infrastructure investments bankrolled by private enterprise. The project will cost R$150 million in total, funded through the PPP consortium, federal and state funds associated with PAC 2, and funds from city government.

It is important to note that the city-funded changes to the neighborhood are said to be under the guise of the Morar Carioca favela upgrading program. This has created some confusion since the “Morar Carioca” label is generally associated with participatory and pro-community upgrades, an extension of the Favela-Bairro program funded by the Inter-American Bank since 1995. Yet in Providência’s case the intervention termed “Morar Carioca” involves the demolition of over 800 homes and the community’s only widely used public square, for what residents argue is essentially a tourism project.

Infrastructure changes to Providência are scheduled to be completed in 2013. The gondola will have three stations: Cidade do Samba (“Samba City”) in Rio’s Port, Providência, and the central train station Central do Brasil. In addition to the gondola, a furnicular tram inside the community will provide another means of getting up the signature steps of Providência. According to Housing Secretary Jorge Bittar, “the re-urbanization of Providência is fundamental to the revitalization of the Port Zone.”

But according to residents, evictions are happening arbitrarily. A lifelong resident and young professional photographer, Diego de Deus, explained the city’s procedure as they announced his building, located next to the projected gondola station, would be removed. “First they told us it was going to be removed because of landslide risk. Then when we asked for proof, they eventually came back and told us that no, it had to be removed in order to make way for a corridor. But then more recently they said it would be for new housing, just not for us.”

In January of this year Secretary Bittar said that 300 families would be relocated; in April, the number was amended to 800. Some of the families live in at-risk areas and are willing to be relocated for safety reasons, but others live on land that will be used for questionable urbanization projects, although officials like Bittar and Mayor Paes tend to conflate the two. Relocations, whereby residents consent to moving, are occurring in Pedra Lisa, an area threatened by landslides. Unconsensual evictions, however, characterize many of the other marked homes. Bittar affirmed that evicted residents will be resettled in Minha Casa Minha Vida housing projects in nearby neighborhoods down the hill, and receive rent money in the meantime. Yet Minha Casa Minha Vida programs in Rio have been characterized by lower quality construction than existing homes in Providência with greater density and less conducive to solidarity-building activity. They are also known to constrict resident rights: residents are not allowed to run businesses from their homes, have pets or other domestic animals, or practice religion in common spaces. All of these are common practices in Rio’s favelas and promote community-building as well as providing buffers during hard economic times. In Providência’s case there is an added preservation concern given the unique historical role of the community as Brazil’s first favela, not to mention the neighborhood’s relevance to Afro-Brazilian history.

As is common practice across the city, the Municipal Secretary of Housing (SMH) marked houses for removal with spray-painted SMH tags, without clarification. Some residents complained they returned from work to tagged homes without further information. Many evictions will affect houses near the community’s signature staircase linking the community to the street. The government originally planned to remove people on both sides, one to construct the tram and the other because of landslide risk. Local photographer and community organizer Maurício Hora protested the unnecessary removals by displaying enlarged portraits of residents on the sides of their threatened homes. Despite previous unwillingness to modify plans, city officials then moved the planned tram to the side that was already at risk, eliminating the need to evict tens of residents on the other side.

The Providência gondola station is set to be built on the site of the Praça Américo Brum, the largest and most utilized public space in the community. Residents use the Praça for soccer games, parties, live music, holiday celebrations, and everyday socializing. The only other large public square, Praça da Igreja do Cruzeiro, was redeveloped by the city. Residents explain that it is rarely used for events now because the remodeled space is narrower than it was before. In July residents staged a protest of preliminary land surveys for the gondola station, asking the government to leave them their only leisure space. They complained that government had not shared information about the project with the community because it is primarily meant for tourists.

After the protest the city government held a meeting with residents and community leaders, but the discussion focused on the location of the gondola stations, rather than whether the entire project is necessary.

As a transportation improvement, the gondola is dubious. Providência is a low hill, it doesn’t take long to walk up the staircase, and roads provide access near the top of the community. The Central Station is a 15-minute walk from the top of the hill. Moreover, there is already a road linking the Port Zone to Central do Brasil. Maurício Hora pointed out that a gondola line along the ridge of the hill, rather than across it, would be far more practical since it would link Providência to neighboring communities and serve a real need. Even assuming a new transportation option were needed, constructing a tram and gondola is overkill. It will give tourists travelling between the Port Zone and city center a scenic view of Rio’s first favela, but it comes at a high price for the community.