On December 16, 2010 Mayor Eduardo Paes signed Decree 33.280 to establish Leopoldina Municipal Urban Park in the Serra da Misericórdia, located in the North Zone of Rio. In 2012, the project received a R$15 million (US$7.5 million) investment, of which nearly R$11 million (US$5.5 million) came from the socio-environmental foundation of Caixa Econômica, the federal public bank. Yet, it was recently discovered that the project has been abandoned and the funds returned.

Residents and environmental groups in the North Zone are demanding answers from the City, asking: “Where is the Serra da Misericórdia Municipal Park?”

To mobilize the community and draw visibility to the issue, on August 1 and 2, NGO Verdejar—a widely respected community socio-environmental group responsible for reforesting much of the Serra and operating in Complexo do Alemão since 1997—organized a mutirão (collective action) day of planting, a hike, and an afternoon of music and educational activities. Other organizations from the community collaborated on the event, including Centro de Educação Multicultural (CEM), Barraco 55, and Instituto Raizes em Movimento.

Mountains of Mercy

The Serra da Misericórdia is a rocky massif spanning 43.9 square kilometers in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. The name Serra da Misericórdia, which translates to Mountains of Mercy, is connected to a folktale about the construction of the iconic Church of Penha.

Urban and industrial development in the region, however, has wielded little mercy upon Serra da Misericórdia. The massif’s unique positioning has created tensions between environmental preservation, the urbanization and growth of Complexo do Alemão, and industrial activities.

Edson Gomes, co-founder of Verdejar, explains that due to its location, the Serra da Misericórdia “gains a very strategic socio-environmental importance for the city because it’s the last area of Atlantic Forest in all of the North Zone of the city.” Located within Planning Area 3 (AP3)—an urban planning designation containing the North Zone, the most populous zone in the municipality with over 2.5 million inhabitants—the Serra da Misericórdia is the last expansive green space in the area, bordering 27 neighborhoods.

Edson continues: “It’s exactly here that you have a series of violated rights, including this: the right to a healthy environment, guaranteed by the constitution and various international conventions. This right, like many others in Brazil, is disrespected. It’s not due to the lack of societal and community mobilization that we don’t have this right guaranteed… There are a number of groups that incorporate the fight for the Serra da Misericórdia in their causes. It’s also not due to the lack of law… laws have been established as a product of this movement. So, why are the public authorities absent? Maybe they’re present, but they don’t recognize the socio-ecological potential of this Serra.”

Legislation and Loopholes

2000: Area of Environmental Protection and Urban Recuperation

In 2000, after lobbying by Verdejar and collaborating social and environmental movements in the region, Municipal Decree 19.144 designated the Serra da Misericórdia an Area of Environmental Protection and Urban Recuperation (APARU). In theory, this legislation introduced a broad framework of environmental protections to the area—including “environmental recuperation… preserv[ing] and amplify[ing] biodiversity”—as well as urban development goals, including promoting the “(legal) regularization of existing favelas,” the development of “recreation, leisure, and eco-tourism,” and the development of “environmental education programs” in order to “improve the quality of life of the local population.”

An additional goal envisioned by the legislation was “to promote the compatibility between profiting from [or, taking advantage of] the earth and defending the environment, by means of revising the parameters of use and occupation of the grounds.” This objective refers to the presence of private stone quarries located within the Serra da Misericórdia.

The geological richness of the area brought mining companies to develop quarries for concrete production as early as the 1940s. Currently, three companies continue to operate in the region: the French group Lafarge, Sociedade Nacional de Engenharia e Construção, and Anhanguera.

Verdejar is fed up with the City’s excuses—first legal, then financial—for having failed to enforce environmental protections and implement social and educational activities in the area. Edson speculates that the City “must be trying to attend to other interests that aren’t those of the [local] population. Could it be because within the area there is a multinational enterprise called Lafarge, the owner of Mauá Cement, which is a partner of [construction and engineering conglomerate] Odebrecht in many construction projects of the City of Rio de Janeiro?” Considering the construction boom in Rio de Janeiro propelled by the 2016 Olympic Games, the City’s interest in maintaining local cement producers—dramatically reducing transportation costs—is no surprise.

The continuity of these industrial activities—uninhibited by the APARU designation as the quarries operate protected by environmental licenses granted by the State Institute of the Environment (INEA)—represents an enormous obstacle for environmental preservation efforts in the Serra da Misericórdia.

Though the APARU designation yielded few practical environmental protections, the status gain was a victory celebrated by Verdejar. Edson said: “It was the first decree that arrived—that didn’t guarantee [these protections]—but was the first decree that included the Serra da Misericórdia, categorizing the Serra da Misericórdia as a protected area.”

2006: Serra da Misericordia Municipal Park

In 2006, Mayor Cesar Maia signed Municipal Decree 27.469, establishing Serra da Misericórdia as a Municipal Park. This means the area is defined as a natural park, emphasizing environmental protection, conservation, and education, establishing areas dedicated to public visitation and research, projecting reforestation and native species protection activities, delimiting the bounds of appropriate urban expansion, and harnessing the area’s potential for the cultivation of wind energy.

Similar to the 2000 legislation, this new decree offered the potential for major strides in environmental efforts, but its effects were limited. Edson describes this legislation process as non-participatory—the idea of a natural park was not discussed with social movements or residents of the area. Verdejar’s insistence on opening up public debate over the plans was unwelcome by city authorities, Edson states. He describes: “This decree from 2006, we believe, is the result of [our] struggle—but emerged detached from the struggle because it was created by the cabinet of the mayor at the time, Cesar Maia, who never discussed it with us. Historically, the secretaries of the environment—everyone from the municipality and the State—have seen Verdejar as a non-partner because we are resoundingly radical about the ethical issue of our struggle.”

Verdejar has experienced fraught relations with City authorities over the years, perhaps culminating in 2012 when the organization’s headquarters was demolished by Light, the public utility electric company. The demolition was justified by plans to build an electrical substation, but these plans still have yet to be implemented.

2010: Serra da Misericórdia Municipal Urban Park, Leopoldina Park

In 2010, Mayor Eduardo Paes signed Municipal Decree 33.280. Overriding the 2006 decree, this decree transformed Serra da Misericórdia into a Municipal Urban Park. Under the guise of environmental conservation and social development, this new decree effectively stripped the Serra da Misericórdia of the environmental protections established by the 2006 legislation and placed the area under the jurisdiction of the Municipal Parks and Gardens Foundation.

Edson explained: “We are talking about the fourth largest mountain range in the city. There are hundreds of springs, and it subdivides a quarter of the most polluted water sub-basins of the Guanabara Bay. It’s the last fragment of Atlantic Forest in all of the North Zone of Rio… so it has a very large ecological importance to be considered only an urban park.”

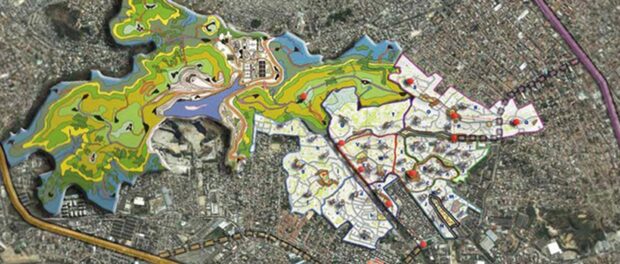

This piece of legislation emerged in the context of the federal Growth Acceleration Program (PAC), charged with infrastructure investments nationwide, but in Rio emphasizing investments in a handful of large favelas. Complementing his PAC designs (including the Complexo do Alemão cable car system), renowned Argentine architect Jorge Mario Jauregui designed a plan for the municipal urban park and a series of urban-ecological corridors to better integrate green space into favela urban landscapes. Yet, Jauregui’s eco-plans were abandoned: the State Company for Public Construction (EMOP) claimed that other PAC interventions took priority.

From Verdejar’s perspective concerned with environmental conservation, categorizing the Serra da Misericórdia as a Municipal Urban Park under the 2010 decree was not ideal. However, the legislation proposed promising new recreational and educational opportunities.

However, the project lacked funding. So, Edson describes, Verdejar organized “a series of actions until the Minister of the Environment released R$11 million (US$5.5 million) to the City through the Socio-Environmental Fund of [the federal public bank] Caixa [Econômica]. The City was going to offer R$4 million (US$2 million) more exclusively to build the park.”

The project, designed by Darsa Architecture and launched as a pioneer initiative of Morar Carioca Verde—a sustainability-focused branch of the now-dismantled favela upgrading program Morar Carioca—planned to create six social activity centers including sports courts, a bike path, hiking trails, recreational facilities, and environmental education programs.

The funds for the park’s construction were secured during the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012. Edson describes: “The City had no more excuses. There’s the law, there’s the project, there’s the money, there’s an organized populace, and so, what’s the excuse? There wasn’t one.”

But rather than beginning construction of Leopoldina Park, the City’s first action after funding was secured was to evict residents in Lagoinha—an area of Complexo do Alemão in critical need of public investment in infrastructure. Verdejar questioned, “What park is this, where instead of guaranteeing the preservation of the Serra da Misericórdia, it came to oppress people who were already being oppressed, who were already vulnerable?” In response to the nontransparent decision-making process to remove families from Lagoinha, Verdejar and other civil society actors pleaded to create a management advisory board for the APARU Serra da Misericórdia. City authorities were unreceptive and no such context for public dialogue manifested.

In a letter dated March 28, 2014, Mayor Eduardo Paes and Municipal Secretary of Housing Pierre Batista wrote to Caixa’s regional superintendent Tarcisio Luiz Dalvi stating that Leopoldina Park would not be built, justifying the unfulfilled promise of six recreational centers with the creation of a lone bike park. The municipal urban park was planned to occupy 240 hectares (nearly 600 acres); the bike park occupies one hectare (2.5 acres).

So, fifteen years after gaining the designation as an Area of Environmental Protection and Urban Recuperation (APARU), nine years after legislation for the creation of a park first surfaced, five years after the executive project was designed, and three years after gaining public investment to implement the project, Verdejar wants to know: where is the Serra da Misericórdia Municipal Park?

Click here to view and participate in Verdejar’s campaign.