This is the latest contribution to our media watchdog series on the Best and Worst International Reporting on Rio’s favelas, part of RioOnWatch’s ongoing conversation on the media narrative and media portrayal surrounding favelas.

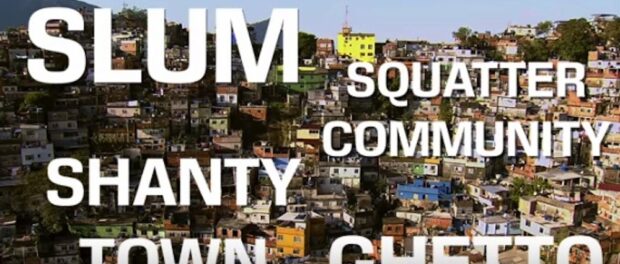

One year from today, the 2016 Olympic Games will draw to a close and global news will be inundated with evaluations of the event and its impacts. In the corresponding Olympic period this August, there has been a heightened media interest in Rio and the Games’ preparations. This heightened attention has produced some truly stellar reporting on Rio’s favelas and the current context of the city, continuing the trend of increasingly productive portrayals of favelas we’ve observed from mainstream English-language media since 2009. At the same time, the single event that drew the most coverage to Rio’s favelas was the death of a wanted trafficker, which shows there is still work to be done to reach more balanced coverage. Furthermore, the use of stigmatizing language that misrepresents Rio’s favelas remains prevalent.

Here, we highlight some of the most nuanced and important articles from Rio from the last couple of months, and draw attention to examples of how favela reporting still needs to improve.

Great Favela Reporting

The Guardian’s “Rio Olympics: View from the Favelas” series gives two respected community journalists a global platform for their reflections. In the first article, Michel Silva, the founder of Rocinha news outlet Viva Rocinha, critiques the Brazilian mainstream media’s portrayal of Rocinha as a “dangerous and dirty place where residents lack an understanding of how the world works.” The rest of his article disproves that portrayal, as he overviews Rocinha’s history and demographics, summarizes what residents are proud of and what they lack, and calls for more “discussion of public security policies with local people.” In the second article, Thaís Cavalcante, a journalist from Maré, highlights last year’s forced evictions in the Salsa and Merengue communities, mega-event impacts that received no English-language mainstream media coverage. These community journalists bring depth and relevance that is rarely equaled by outsiders, and they disrupt stereotypes through their eloquent and passionate writing about their homes.

Recognizing the importance of community journalists, in June Fusion produced an in-depth video about Coletivo Papo Reto, a media collective in Complexo Do Alemão. The video combines footage filmed by the collective and numerous interviews with collective participants, forefronting the residents’ account of their work. In media, violence in favelas is frequently relayed through numbers of deaths, quotes from residents or officials about the severity of the situation, and imagery centered around men with guns and bullet holes in walls. Fusion‘s portrayal of violence in favelas stands out, alongside The New York Times Magazine‘s own article on Papo Reto, for its focus on the constructive actions of residents working to change narratives and end that violence. There are times, of course, when the numbers and stark facts about violence need to be stressed. In May, Simon Romero and Taylor Barnes of The New York Times authored a critical account of Brazil’s police killings in recent years. The article placed Brazil’s shockingly high murder rates and the public’s acceptance of them in the context of the same data and resulting protests in the United States.

Stephanie Nolen’s compelling feature on racial inequality in Brazil for The Globe and Mail exposes the extreme obstacles many favela residents, the majority of whom are Afro-Brazilian, face in combatting a rigid, yet little acknowledged, race-based hierarchy. The author lays out an inherent contradiction: Brazil’s national identity is founded on a celebration of racial diversity while racial inequality is blatantly pervasive in day-to-day life. The article then dives deep into the lives of Brazilian families to demonstrate through complex stories how that contradiction is sustained. The rich historical context provided shows why Brazil has unique concepts of race, but the comparisons drawn to other countries, like the US, strengthen the article’s significance.

Great Olympics Reporting

Of the many articles about Rio published on August 5, marking a year to the beginning of the 2016 Olympic Games, few zoomed in explicitly on issues affecting favelas. Ana Terra Athayde’s video feature on the abandoned Morar Carioca favela urbanization program was a rare exception. The footage showcases public investments in favela Babilônia‘s sustainable, cost-effective projects: public space decks made from recycled materials, solar panels, and rainwater harvesting systems, among others. However, the video also features interviews with residents who say the project delivered fell far short of the projects promised, and experts lamenting the small-scale implementation of the program. With exactly one year to go until the Olympics begin, the fact that a key Olympic legacy project had “ceased to be a priority to the municipal government, with no official explanation,” was an essential message to highlight.

The AP’s investigation into water quality in Olympics and Paralympic venues, published at the end of July, has had immense influence. Referenced in most of the one-year-to-go articles published on August 5, the report provided the results of “the first independent comprehensive testing for both viruses and bacteria at the Olympic sites.” Prior to this report, the City’s failure to clean Guanabara Bay as promised had already received considerable attention, but the data collected by the AP sparked official responses from the IOC and the Rio Organizing Committee. The latter reaffirmed a commitment to pushing the government to clean the bay.

Finally, Jonathan Watt’s compilation of perspectives from ten people living and working in Rio for The Guardian deserves recognition. The article highlights the ongoing struggle of Vila Autódromo residents against evictions through the story of long-term activist Jane Nascimento. Another activist featured is Marcello Mello, whose fight against the construction of the Olympics golf course on environmentally protected land has received surprisingly little English language coverage. Watts also produced an excellent profile of Brazilian property tycoon Carlos Carvalho, whose vision for a city “of the elite, of good taste” was a shockingly candid insight into Olympic real estate developments in Barra da Tijuca.

How Favela Reporting Needs Improvement

Despite dramatic improvements from previous reporting, the tendency for international journalists to describe favelas with inaccurate language remains. One article from The Independent on August 4 makes a fundamental point: the realities of favela residents “will be lost amid the talk of qualifying times, stadium deadlines, water quality and hotel prices.” The majority of the article contains strong critical evidence of corruption and failed legacy promises. However, the author writes: “Scattered all around are another 600 slums housing 1.3 million people in huts amid sewage and sorrow.” This line makes Rio’s diverse favelas—pacified and unpacified, old and new, those with land titles and brick houses and those that contain shacks—sound all exactly the same: impoverished, miserable, and temporary. Inexplicably, the author states that “you would not dare ask those in Vasco (a favela) about what the Games will mean to them.” Why not ask? Why not seek out opinions of the Games from those most affected by them? Yet the article’s only quote from a favela resident discusses how drug dealers bury bodies under the soccer pitch.

Even a New Zealand Herald article that derides the mainstream media’s affinity for “poverty porn”—”where the plight of the poor is packaged up for the entertainment of the not-poor”—is guilty of misrepresenting Rio’s favelas in between its important critiques. The author describes Rocinha as “a melting pot of the poor and needy…a world of youth gangs, violent crime and drug dealing…a no-go zone for outsiders.” In fact, Rocinha has a booming local tourism industry and is home to parts of the “burgeoning middle class” the author later mentions. Gangs, crime and drugs are a part of Rocinha’s world, but so are culture, entrepreneurship, and commitment to sustainability. In criticizing the media for focusing on Brazil’s poverty over its less “sexy” successes, the author falls into the same trap for Rio’s favelas.

Another article, from Australia’s Herald Sun, gives a fair and important overview of competing resident perspectives from Vila Autódromo. The author provides what appears to be a balanced description of the community: “Vila Autódromo had the dirt roads, sometimes shaky, amateur housebuilding, and open sewers typical of favelas, but none of the usual drug-fueled violence, winning a reputation as a laid-back place for working class people to raise families.” The problem with this description is what’s missing—the City paved the roads of neighboring community Asa Branca, but many Vila Autódromo residents believe the City has intentionally not paved their streets in order to keep the neighborhood appearing temporary, despite holding titles for two decades. What may have appeared to be “open sewers” were likely just puddled water, as the community built a simple sewage system itself. And, before their brutal eviction began, the vast majority of homes in Vila Autódromo were completed and solid, with only a small fraction ‘shaky or amateur, and many were 80m2, larger than homes in the vast majority of favelas.

During this one-year-to-go period, the favela story that drew the most international attention was the killing of wanted trafficker “Playboy” on August 8. The substantial attention to a violent event that is unlikely to change much about Rio’s entrenched drug trafficking system is in itself unfortunate. The Telegraph’s coverage mentions that Playboy had called “for a ceasefire between gangs to stop bullets from hitting innocent members of the public,” despite not wanting to end the “blood war.” Coverage by Australia’s The Daily Telelgraph placed the druglord’s death in the context of police killings in Rio, and mentioned that “relatives of Playboy claim he was trying to surrender and was killed in cold blood.” The Telegraph and AFP reports both excluded this context and perspective.

How Olympics Reporting Needs Improvement

Among the one-year-to-go articles, there is an overwhelming focus on the question of whether Rio will be ready to host the 2016 Olympic Games a year from now. One headline from The Daily Telegraph read, “The race is on to have Rio ready for the Olympics,” while a Miami Herald headline stated: “With Summer Olympics a year away, Brazil wonders if it’s ready.” A Globe and Mail article asks more subtly within the text: “Will it all be ready?” Individually, these are thoughtful articles that are skeptical of Olympic legacy projects and ask important questions about the Games’ costs. Yet a collective focus on the question of whether the Olympics will be logistically ready by next August risks setting a low bar for success. As mega-events researcher Christopher Gaffney noted, the dominant media narrative that Brazil’s World Cup preparations would not be ready in time allowed FIFA and Brazilian organizers to claim the event was a success when infrastructure was (mostly) ready in time, regardless of the tournament’s long-term impacts. Key to holding the 2016 Rio Olympics accountable will be media coverage that emphasizes the tougher questions of costs and impacts on citizens over the easier question of whether the Games infrastructure will be ready.