Rio de Janeiro is currently in a special spotlight as athletes, fans, nations and the global media reflect on the one year remaining to the 2016 Olympic Games, set to end exactly a year from tomorrow. The emphasis has been on the question “Will Rio be Ready?” asking whether the city will be prepared to host a 3-week one-time event and whether it will be prepared to receive Olympic events and visitors. Little, in comparison, is written about the treatment of Cariocas, or Rio’s citizens, and how the City of Rio conducts itself for them. Well over R$24.1 billion (US$10.76 billion) will be spent on infrastructure and development projects in support of the Olympics, but few residents are seeing improvements. Is quality of life improving for Cariocas? Or is the money merely spent “para inglês ver”—for the English to see—and serving private interests? What are the City’s priorities?

Three troubling trends have exacerbated the marginalization of favela residents, comprising the most vulnerable quarter of Rio’s population: critical threats to sanitation and education have gone unaddressed; showy infrastructure has received investment ahead of those basic needs; and private interests have been prioritized. It is time to ask if the government is selling out its people and valuing consumers over culture. Local and Western media have at times taken note of the pervasive misplacement of public priorities, especially at the expense of favelas, but few have captured the full magnitude of the issue.

Underinvestment in Basic Services

Sanitation in Rio has reached crisis levels. The Ministry of Cities notes that “30% of the population in Rio de Janeiro is not connected to a formal sanitation system, and even in areas with formal connections, only about half of sewage waste is treated before entering into waterways and eventually the ocean.” This figure does not even account for many of the city’s informal areas, so the actual percent of the population with formal sanitation is likely lower. Compared to 96.1% access in São Paulo and 100% in Belo Horizonte, Rio’s numbers are staggeringly low.

Sanitation kills. Untreated waste from the Faria-Timbó River flows through Complexo de Manguinhos into Guanabara Bay. At least three Manguinhos residents died due to lack of sanitation in 2013. Favela residents have grown accustomed to unmet promises for improved sewerage infrastructure from politician after politician, from Mayor Paes to State Governor Pezão, former President Lula, and current President Dilma Rousseff. A study commissioned by the Luiz de Queiroz College for Agriculture found that spending on health and sanitation is the best way to reduce poverty, yet the government has pushed aside the calls for investment in favelas rather than tackling this pressing issue. Some favela residents, such as those in Vila Kennedy, have been able to temporarily fend for themselves through community cleanups in place of public services, but such an approach to sewage is rarely sustainable.

The effect of poor sanitation on children is distressing. Those with access to sanitation have 18% higher educational attainment than those without. The shortage of sanitation investment is therefore at sharp odds with the government’s stated focus on improving education both in the city and across Brazil. Children in Complexo do Alemão, one of the largest favelas in Rio’s North Zone, play in piles of garbage due to a lack of formal recreational spaces. A study showed most deprived areas of the city have substandard public spaces, and even once-suitable recreational spaces have fallen into disrepair. Pleas for improvement have fallen upon deaf ears.

The right to education is guaranteed by the 1988 Brazilian Constitution, but children in favelas are frequently denied full access to this right. Schools are disrupted on the occasions of police operations and some even on a more permanent basis by the presence of local Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) initially aimed to ‘pacify’ favelas through community policing, but in North Zone communities ultimately behaving like an occupation force. In one case in 2013 in Complexo da Maré, armed police scaled school walls without authorization and searched students, closing schools for four days. Armored vehicles and occupations make students feel as if they are caught in the middle of a war. In Alemão, the installation of a UPP base at the Caic Theóphilo de Souza Pinto School has coincided with a dramatic decrease in school attendance. Bullet holes in the school’s walls testify to students’ experience of violence in their place of learning. Following a community meeting in May, officials promised the UPP base would be removed from the school, but as of today the base still remains. Another site tentatively allocated for the construction of a university campus in 2011 was occupied by the UPP in 2012, and the university still is yet to be built.

The UPP Social initiative, intended to go hand-in-hand with police pacification, aimed to “integrate” favelas into the formal city by promoting opportunities for resident participation to guide investment in the community. The City’s effort to rebrand UPP Social—as ‘Rio+Social’—is in itself a testament to that initiative’s failures. Many favela residents do not believe in the program’s stated commitment to participation. “They ask because they have to, so they can say they asked,” one resident said. Unfortunately, community “participation” is normally at most a process of informing residents of what is set to happen, or “consulting” residents with no intention of implementing their recommendations. While responsible for UPP Social, former Secretary of Finance of the Municipal Government of Rio, Eduarda La Roque, explicitly stated: “In reality the priorities are those of the city of Rio de Janeiro as a whole. We are paying taxes to invest R$1.8 billion in Rocinha, so the society as a whole has to identify the priority. [We do not] have to cater to what the favela wants.”

Misplaced Public Infrastructure Investment

When public money does reach the favelas, it is often for projects that residents do not desire, or even actively oppose. The cable cars in Complexo do Alemão and Providência, and the planned construction of one in Rocinha, have become issues of contention. “It’s an unwanted gift,” says José Martins de Oliveira, a Rocinha resident. These cable cars can cost hundreds of millions of reais and many believe their construction caters primarily to tourists. Residents instead desire improved sanitation and education.

Some favela residents laud the conveniences of cable cars, while others complain that the cable cars cannot support the transportation of construction materials, are inaccessible to persons with mobility issues, and even destroy homes. Residents of Alemão and Rocinha are taking legal action against the government for violating federal law 10.257, which requires public participation in government interventions.

In Contrast: Catering to Private Interests

The image that Rio projects for World Cup and Olympic visitors is a far cry from the lives of its average people. Poverty and exploitation are swept away. Favela resident Maria Christina noted: “Everything is for the gringo to see. A mulatta is hired to dance samba and after her shift, she goes back to the favela to sleep in a shack.” There is little distinction between public and private funding for the Games, and Piedade resident Fernandes Tavares speculated: “I think they took from our children to build stadiums.” A Penha resident asked why the City would build modern stadiums just for the Games if millions of Cariocas “do not have public health, security, or quality education.”

Another area of grave concern is the increasing privatization of the city and “selling out” of Carioca culture. Rising property values have made favela communities and their residents personae non gratae. Residents have been told that their homes are “at risk,” but many of those “areas of risk” are located in the most lucrative parts of the city, or those with the most potential to become lucrative. Architect Lucas Faulhaber noted: “The Olympics are not the real reason for removals. They serve as a justification to legitimize evictions, as well as a reason to press on with the timeline. The real motive is property speculation.” Unfortunately most communities do not have the resources or technical support to question the government’s verdicts, as residents of Santa Marta did.

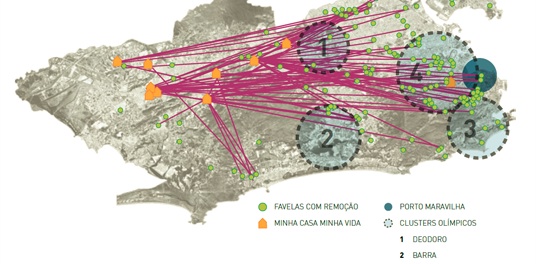

Over 70,000 people have been removed from their homes, but there is little Brazilian mainstream media coverage. While they are often shipped to the West Zone, to areas controlled by drug traffickers or militias, luxury condominiums will take the place of communities where homes have been passed down from one generation to the next. Many are displaced so far from their jobs that they need to take a second or third bus to commute. Some residents lose their jobs because employers refuse to pay these extra costs.

One of the most devastating side effects of both the Olympics and the 2014 World Cup is the fetishization of security and the militarization of the city. Favela residents have been deemed dangerous, their communities unsafe. Police occupations are often seen as establishing residents as ‘the enemy’ in war. Rio’s Military Police is statistically one of the most violent in the world and “violent deaths with unknown intention” (VDUIs) are on the rise. On RioOnWatch, researcher Patrick Ashcroft wrote: “In 2006, 1,676 were victims of VDUI, but by 2009 there were 5,647 cases, accounting for 60% of all violent deaths. The state then reevaluated some of that year’s cases, bringing the number down to 3,587; yet Cerqueira estimates some 3,165 murders in 2009 were not reported as such… In 2007 the ISP registered the highest number of autos de resistência, the term for deaths caused when suspects ‘resist arrest,’ in Rio’s history—1,330 in just one year.”

Beyond the violence and displacements, the Olympics also encourage economic inequality. The Olympic projects lead to an enormous transfer of wealth into private hands. The middle and lower classes are left out of this supposed development of the city, and geography professor Christopher Gaffney argues these classes cannot hold anyone accountable after World Cup and Olympic governance structures disappear at the conclusion of the Games.

Recent policies and projects suggest the government believes that the value of land is solely measured in dollars or reais, rather than by memories and community. Community bonds are broken when historic schools are demolished and museums are threatened with eviction. One resident of Maré argued that the recent eviction threats against the famous Museu da Maré were linked to real estate speculation and the state’s desire to “make favela culture invisible.”