For the original in Portuguese published in Folha de São Paulo, click here.

Rio’s favela residents share their views of the 2016 Olympics and of the pacification process of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs).

Embedded in Complexo do Alemão, one of the biggest agglomerates of favelas in Rio, there is a municipal library, a center for digital inclusion, and a 3D cinema. They are part of the Morar Carioca program, announced by City Hall as the primary social legacy of the 2016 Olympic Games.

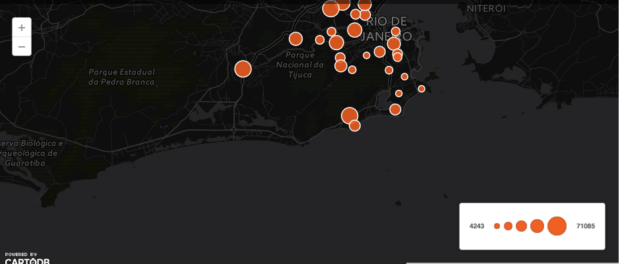

With an expected budget of R$8.5 billion (US$2.4 billion), the program was launched in 2010 with the ambitious promise of upgrading all of the more than 700 favelas in Rio by 2020, bringing paved roads, street lights, running water and sewerage, as well as schools and social facilities.

On the morning of July 2, when Folha was to visit Alemão, a gunfight between police of the local UPP and supposed traffickers made the Municipal Secretary of Housing cancel the appointment. “It’s not safe,” stated the press office.

On that day a 27-year-old housewife was hit in the chest by a stray bullet on the pavement outside her house. An 11 year old boy took a shot to the leg as he returned home from a game of soccer. He went into surgery and he’s doing fine.

The episode isn’t unusual: over 15 days between the end of June and the start of July 2015, at least one person was killed and five injured by stray bullets in Complexo do Alemão.

This statistic reveals the knot that ties the destiny of the most underprivileged areas of the city to a security policy which is more and more under scrutiny, whether due to the lack of preparation of some of the police officers, or because it wasn’t accompanied by a significant increase in the amount of quality public services on offer—the so-called UPP Social—as promised.

“We are talking about a core, structural, project. But, because UPP Social never left the drawing board, the police were left on their own, and they can’t solve the issues of poverty and inequality,” summarized Guiseppe Cocco, professor of political theory at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

For Roberto Alzir, special sub-secretary of security for large events, “every shot, every confrontation, every bit of bad news on public security are steps backwards in the effort made since 2008 to implement the UPPs.”

Alzir believes, however, that these incidents shouldn’t happen during the Olympics, when the presence of police, armed forces and federal police will increase across the whole city. “Our challenge is to turn this into a permanent sense of security,” he says.

For some residents, however, the feeling is one of segregation. “The governments are not concerned with the security of the favela. Deep down, they want to protect society from the people here. With this, the Olympics has created more distance than inclusion,” concludes Mário Sérgio de Souza, member of the favela NGO CUFA, in Vila Kennedy in Rio’s West Zone.

“We are the entrance point to the city, that’s why they’re worried about us,” says Janna Salamandra, from the Theater of the Oppressed, in Complexo da Maré, which borders access routes to Galeão, the city’s international airport. “The army left here without being replaced by the UPP. They only put police posts around the edge of the favela. Nothing here, inside. Who are they protecting?”

For Sérgio Magalhães, president of the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB) and creator of the Favela-Bairro program [precursor to Morar Carioca, launched in 1994], the favelas are still a priority subject for public security: “Where today there is almost hegemonic police presence it’s because the civil part of the government is almost non-existent. The UPP has it’s problems but it’s still the best solution that’s been found so far.”

Where is the legacy?

In this context, even with less than a year to go to Rio 2016, there is still a lack of clarity regarding what can be considered an Olympic legacy for these areas, which are home to approximately 20% of the population of the city.

On the one hand, the government maintains that the Brazilian Olympics have been the catalyst behind efforts and resources, such as urban development, mobility and security, that will particularly benefit residents of these communities.

On the other hand, residents, activists and researchers have denounced the events which have legitimized forced evictions in favelas, real estate speculation and construction which do not serve local priorities—where basic sanitation invariably occupies the top of the list.

The Mayor of Rio, Eduardo Paes, states that around R$4 billion (US$1.15 billion) has been spent on urban development in favelas as part of the Morar Carioca program.

The president of the IAB, an organization which mediated the contracting of 40 architecture firms to design urban solutions for Morar Carioca, says the program faded out after 2013, when the contracts with the architects were all canceled without explanation. He points out that now the process is being managed by contractors.

The Mayor argues that the program needed to remove “the exaggeration of the architects… I gave assurances that it would be put into the works. And now IAB says that Morar Carioca has ended. It hasn’t ended. But the money for architects has ended. The works are in full swing,” he says.

Gentrification

Construction has also been used to justify the eviction of communities. “The Olympics have acted as a catalyst for arguments that are used to legitimize the process of removing favelas. They occur with complete lack of participation from the residents,” says Alexandre Mendes, former public defender and professor of law at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ).

He cites the example of Vila União de Curicica, whose residents were informed of the removal of 700 houses for the construction of the TransOlympic BRT line, considered a legacy of the Games. After protesting the planned works, they managed, after negotiations, a reduction in the removals to just 190 houses.

In the case of another BRT line, the TransOeste, Mendes says that there wasn’t any dialogue: the favelas Vila Harmonia, Vila Recreio II and Restinga were wiped from the map of the city. Many residents were relocated to places where their journey back to the affected area of residence takes more than two hours, in houses developed by the federal government’s Minha Casa Minha Vida program, which have been criticized for poor quality construction.

Mayor Eduardo Paes denies that there have been any forced evictions. There are however videos shared on social media which document the actions of the local government, as well as complaints made by the UN and by MIT’s (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) research network on displacement, in the USA.

According to the City, the only case linked to the Games is that of Vila Autódromo, which neighbors the Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca, and which has been targeted with attempted evictions by the public authorities since 1993. Almost a third of residents who live there are still resisting removal, among the debris of the other buildings, semi-demolished by the authorities. The area is considered to have some of the highest potential for valuable real estate in the city.

As well as the Games’ lack of social legacy for favelas, the residents also question the wasted opportunity in terms of sports for this section of society.

“I’m in the biggest favela close to the epicenter of the Games, and I don’t know of a single Olympic project being developed here, whether by the City, State, or federal government or the Olympic Committee,” says Leonardo Bezerra, teacher of physical education and founder of the Sport, Health and Citizenship Project, which gives football coaching to adolescents in City of God.