On Tuesday, September 29, 17-year-old Eduardo Felipe Santos Victor was shot dead in the Providência favela, in the Port Region of Rio de Janeiro. The official report released by the Military Police after Santos’ death stated that the adolescent died “after responding to the arrival of the police with gunfire,” implying the killing constituted an act of self-defense by the policemen. However a graphic video shot by a local resident and posted on social media documented police officers planting a gun on Santos’ body.

In the video, five policemen are shown standing next to the body. One of the officers shoots a gun in the air, while another takes a weapon, cleans it, places it in Santos’ hand and shoots it twice in order to leave gunpowder tracks. The woman that recorded the video has reportedly been threatened by police, and has been offered protection by the Civil Police’s Homicide Division.

The video was posted on the same day shortly after the shooting and quickly went viral. By nightfall, the five officers involved were arrested and it was announced they will be charged with “procedural fraud” for altering a crime scene. The lawyer defending three of the five policemen claimed the shots were fired to unload the weapon and safely transport Santos’ body, but Homicide Division’s André Leiras found this version to be incompatible with the crime scene and statements given by the other two officers. Later that day, Tuesday September 29, it was reported that Military Police officer Paulo Roberto da Silva had confessed to shooting Santos. And by morning Civil Police chief Fernando Veloso had announced that from now on all “self-defense” killings by police will be investigated by the Homicide Division which previously only handled cases achieving high visibility.

An anonymous witness stated that Santos surrendered before he was killed. The witness said Santos had a gun but did not fire and had his hands raised when the police officers shot him. He said: “He should have been arrested, yes. But not killed.”

The autopsy report released on October 1 revealed that Santos was shot while lying on the ground. According to the report, wounds show that the youngster fell down after being kicked, punched or hit with a rifle butt, and only later shot.

National and international media reaction

While the killing of an 11 year old in Caju by the Military Police only one week before was only minimally reported in the national press, and while it took the international media five months to report on the devastating eviction of Favela do Metrô starting in 2010 following local reports, Eduardo Santos’ execution received widespread attention from both the national and international mainstream media immediately. The evidence filmed by a community witness and quickly uploaded onto social media provoked local mass news reporting that included community perspectives and challenged the authorities’ reactions, as was also done by the BBC and The Telegraph, showing a groundbreaking shift in the ability of community-reported events to break and reach mass in moments.

The vital role of social media in this case was recognized in The Guardian‘s report, which highlighted that although execution-style killings are commonplace, it is only “when incidents are filmed that justice is done.” Indeed, the fast dissemination of the video on social networks put intense pressure on Rio’s authorities to react to the increasing outrage expressed online. Providência residents took to the streets to express their rage and Santos’ funeral on Wednesday, September 30 developed into a protest staged in front of Central do Brasil train station.

The role of video & social media

Eduardo Santos’ death and the video proving police corruption and brutality has thrown a spotlight on the role of social media in reporting police violence and on the importance of video recording in order to show evidence of grave human rights violations.

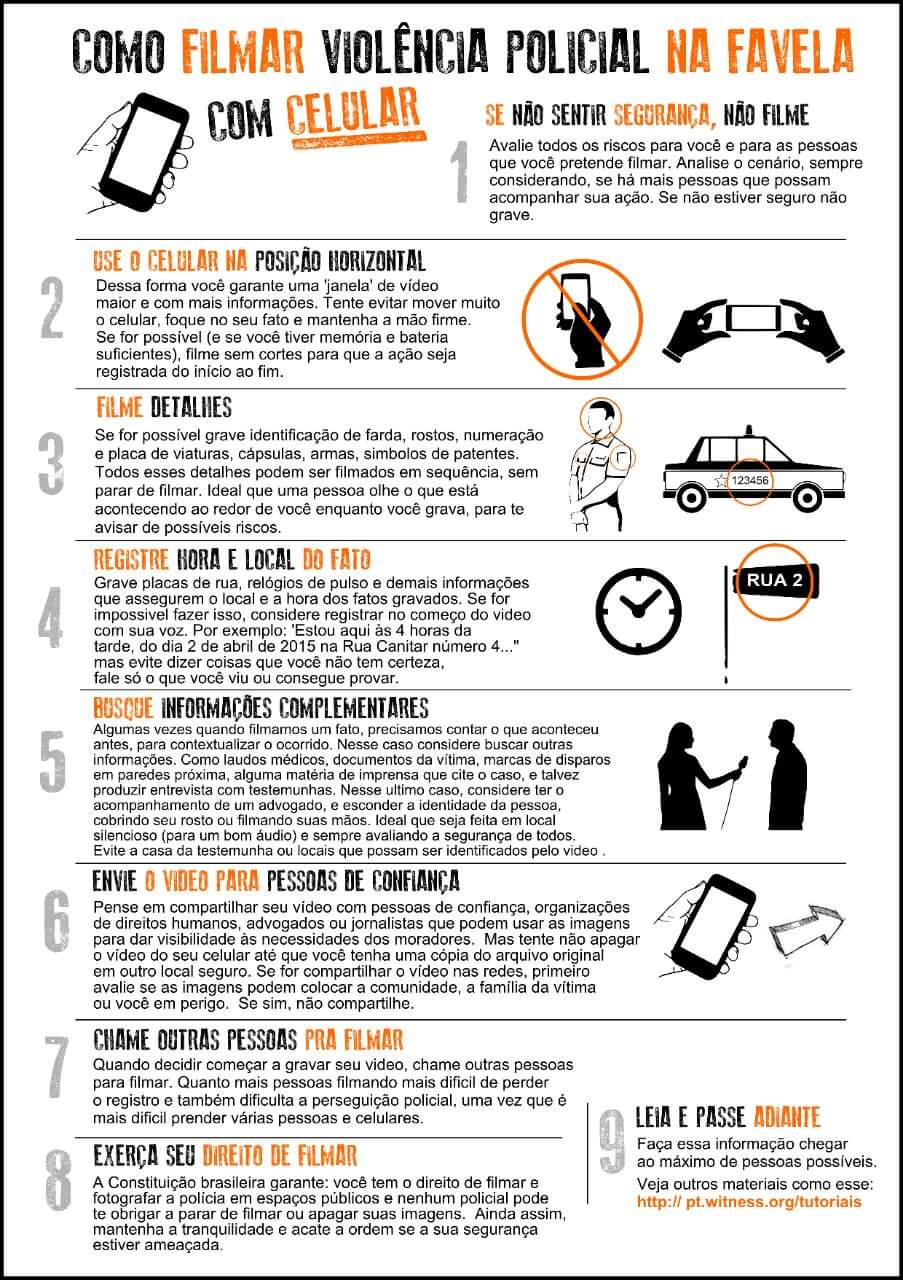

Raull Santiago, an influential organizer from the Alemão community media collective Coletivo Papo Reto, posted a nine-step flyer explaining how to effectively film police violence in the favelas. The guide advises residents to film single-shot videos, record horizontally to include more information, highlight relevant details (faces, ID numbers, weapons, license plates, etc.) and include proof of the incident’s time and location.

The participation of residents in filming such events is on the rise. During a police incursion in Alemão on September 30, Raull’s thread included comments from community members like “Residents, charge your mobiles and keep your cameras active. The best way to combat abuses, is showing everyone with photos and videos!” and “All with cameras in hand, may God protect us all!”.

The guide emphasizes that recording police officers in public spaces is a right granted by the Brazilian constitution but it is important to prioritize safety and to evaluate the possible risks that filming might entail:

The recent violence in Providência exists within the broader context of militarization of Rio’s favelas. The day following Santos’ death, Coletivo Papo Reto posted that in the majority of Rio’s “pacified” favelas, the only representation of the State is the Military Police: “We’re constantly told that we must abide by the laws of this country, that we have to be ‘good citizens.’ Shouldn’t the arrival of State services be the first example of ‘compliance with the law?’” They also criticized the authorities’ claim that the tampering of the crime scene at Santos’ killing was an isolated event: “How many isolated cases make a scandal?”

This year alone 459 deaths have been registered by police as self defense killings, an average of 57 per month and a 30.4% increase over last year. Were it not for the video documenting police interference with the scene, Santos’ execution would have been registered as another such death. In light of this, a petition has been started to demand the creation of external control mechanisms to investigate killings by Rio’s Military and Civil Police, which are currently investigated by the police itself.