![Time for the Bulldozer [Photo by Lianne Milton]](https://rioonwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/20130225evictions480-620x264.jpg)

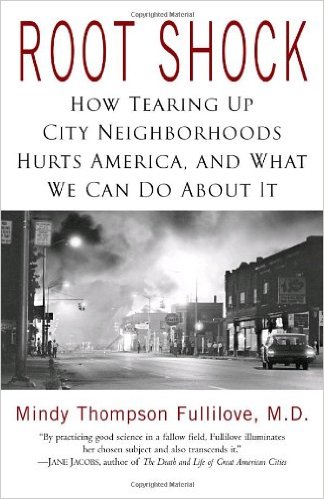

In the field of psychiatry, there has never been a word that formally diagnoses the pain and trauma resulting from being removed from a home. In her book, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It, research psychiatrist Dr. Mindy Fullilove gives this phenomenon a name: root shock.

“Root shock,” Fullilove says, “is the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or parts of one’s emotional ecosystem.” She later adds: “Root shock, at the level of the local community… ruptures bonds, dispersing people to all the directions of the compass. Even if they manage to regroup, they are not sure what to do with one another.”

“Root shock,” Fullilove says, “is the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or parts of one’s emotional ecosystem.” She later adds: “Root shock, at the level of the local community… ruptures bonds, dispersing people to all the directions of the compass. Even if they manage to regroup, they are not sure what to do with one another.”

The book focuses on the destruction of predominately black neighborhoods by “urban renewal” policies in the United States. By Fullilove’s estimate, nearly 1,600 neighborhoods were destroyed in the period from the 1949 Housing Act through the 1960s. “This massive destruction caused root shock on two levels. First, residents of each neighborhood experienced the traumatic stress of the loss of their life world. Second, because of the interconnections among all black people in the United States, the whole of Black America experienced root shock as well. Root shock, post urban renewal, disabled powerful mechanisms of community functioning, leaving the black world [in the US] at an enormous disadvantage for meeting the challenges of globalization.”

During the immense migration of black Americans to cities following slavery, they settled largely in central urban areas that “were the beginning and the end of their options for housing. As [those] neighborhoods became ‘black,’ segregation created a boundary that was rigidly, and even violently, enforced.” In the US, “Black America [was]… a many-island nation within the American nation.” Following Brazil’s participation in the atrocities of the slave trade, in which about ten times as many black slaves arrived in Brazil as were sent to the United States, Brazil never had a structural apartheid like the US. However, freed slaves congregated in urban areas like Rio’s Port region and often found refuge in favelas, such that segregation became an urban reality anyway. According to the 2010 census, over 63% of Rio’s favela residents are black, compared to just 1.5% in Lagoa, Rio’s wealthiest neighborhood.

Fullilove describes urban African-American communities as places that “evolve[d] over time, as each effort at problem resolution [became] part of the collective memory.” Similarly, in Rio’s favelas infrastructure and community identity have evolved constantly and, without significant state intervention, organically. Although sometimes stereotyped as impoverished and crime-ridden, in reality, favelas are rich in history and full of entrepreneurship, sustainable living practices and culture. Crime and poverty are not inherent, but rather the product of systematic isolation from the formal city and lack of opportunity due to stigmatization, both of which make favelas easy targets for criminal elements.

In Roanoke, Virginia, the process of urban renewal scattered African-American residents around the town. One resident described his original neighborhood’s “tight community”—the stroll of ‘howdy’s’—that resulted from “an active street life” as residents walked everywhere. After removal, the resident highlighted the struggle of the “loss of old friendships” and the shift away from pedestrian street life towards greater car use due to being more spread out. “No longer were people likely to walk down the street saying ‘Howdy’ to the right and to the left.” These characteristics of strong community identity and familiarity in neighborhoods better suited for pedestrians than drivers are paramount to favela life too. And because these traits are organically created, it is proving immensely difficult to recreate them in Rio’s planned public housing neighborhoods, which is why organic communities should receive recognition and protection.

Furthermore, Fullilove’s research suggests the impacts of scattering the members of a neighborhood are not only social, but political and cultural. Sala Udin, a member of the city council for Pittsburgh’s Hill District, said, after being displaced from his home: “We are scattered literally to the four corners of the city, and we are not only politically weak, we are not a political entity… And, all of that, I think, contributes to a broken culture, broken values, and a broken psyche, and weakness in this city.” In the context of the active organizing efforts in Rio’s favelas, we must consider how much harder fighting for rights becomes when established networks are broken up and residents are moved to militia-dominated housing that controls political organization.

Fullilove offers this word of caution on the consequences of tearing neighborhoods apart without a massive-scale plan to repair the damage done: “Absent the appropriate post-disaster remedy, it was in a state of overwhelming injury that black people faced a series of crises: the loss of unskilled jobs, the influx of heroin and other addictive drugs… violence… The present state of Black America is in no small measure the result of ‘Negro Removal’.”

Unfortunately, the significant parallels between Rio’s current public policies and former US urban renewal policies suggest Rio policymakers are unaware of the vast literature on US housing failures, including Fullilove’s warning. In the US, urban renewal was seen as a synonym for “progress” throughout the 1950s, though it lacked public participation. Fullilove writes: “Conspicuously absent from the picture, and from the decision-making processes, were poor people, black people, and women.” In Rio, everything from the p0licing program to housing and infrastructure have suffered from subpar participatory processes. The City government has ignored the Vila Autódromo community’s proposed (and internationally recognized) People’s Plan for the neighborhood’s development alongside the Olympic Park.

Fullilove’s book is full of statistics on the history of America’s failure to provide adequate affordable housing for its population. In Newark, only 3,760 low-income housing units have been created since 1959, whereas approximately 8,000 units have been demolished in the name of urban renewal. In Detroit the numbers are more drastic; only 758 units have been built since 1956 despite almost 12,000 families being displaced. In Rio, the favelas serve as affordable housing for lower-income residents, so they are essential to guaranteeing the city is accessible to all. If they’re not preserved as such, Rio will see ever greater skyrocketing housing costs and gentrification even more than many American cities have experienced, given Rio’s complete lack of regulation of the housing market (US cities regulate at some level).

A main critique of American urban renewal is that it overtly and inadvertently stripped downtown areas of residences and replaced pedestrian street layouts with “megablocks and mega buildings surrounded by parking lots.” Despite some well-intentioned public policies to rebuild or upgrade poorer black neighborhoods in the center of cities, profiteering incentives took priority for many municipal governments which were persuaded to sell land to private developers to increase their tax base. In Rio, with the Olympics less than a year away, it is clear that this city too is beholden to private construction and real estate interests, and time will tell whether the city authorities will let these forces govern Rio at the cost of the favelas and affordable, accessible housing in general.

Finally, Fullilove argues: “When all the fancy rhetoric about ‘blight’ is stripped away, American urban renewal was a response to the question, ‘The poor are always with us, but do we have to see them every day?’ The problem the planners tackled was not how to undo poverty, but how to hide the poor.” Those being evicted today in Rio are being moved to the far peripheries of Rio in the West Zone, away from richer neighborhoods that are popular with tourists or developers, and experiencing a reduction–not improvement–in their quality of life, much like how Black Americans were removed to the peripheries of US cities.

Fullilove’s narrative of the failures of urban renewal in the United States is detailed, enlightening and poignant in its own right. When compared to the current injustices in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, however, this narrative is even more poignant because of the striking similarities–and warnings. Fullilove urges us to see “a city is not so much a solid, however solid it looks, [but] a fluid, constantly taking new shapes as we clear and build, clear and build.” She warns that a rigid apartheid-like system leads to greater distress. Her remedies include being conscious of the subtle divisions that are reinforced by public policies, like race and class, and building sufficient quality affordable housing, something both Brazil and the US have failed to do well.