The Quilombo das Guerreiras occupation is a symbol of resistance and community organizing. From 2006 through 2013 over one hundred families occupied and built a community in an abandoned warehouse in Rio’s Port region. Beyond providing housing, the occupation had developed a collective way of living and held activities including literacy tutoring, agro-ecological urban gardening, film screenings and tours.

Occupants joined with various social movements to fight for the right to housing and resist eviction, mounting an exemplary resistance campaign. However pressures to evict occupants mounted as the region gained high profile investments and remodeling as part of the Porto Maravilha Port regeneration program. The Quilombo das Guerreiras’ building was then expropriated by the federal government in late 2013.

RioOnWatch caught up with Maria Ivanilde Moraes, one of the leaders of the occupation, to hear her story of resistance and struggle as part of one of Rio’s most successful and important urban occupations.

Originally from the northeastern state of Maranhão, Maria Ivanilde Moraes, known as “Nilde,” says she used to live in a nice house in Rio Grande do Sul in the south of Brazil with her husband and three sons: “I was married. Both my husband and I had jobs. Then I got divorced and was left with three sons, aged 14, 6 and 3.

“I came to Rio with nothing and found a place in a favela. Many shootings, an empty house, no sofa, no table, no beds, just four walls and a roof. I moved there with a lot of courage and help from my mother. I put the boys into an all-day school and found a job as a maid. I just grabbed whichever job was available. Three times a week, to pay rent and buy bread and milk. Luckily, the boys could eat at school. Becoming part of an urban occupation was the last thing on my mind until all of a sudden, I lost my job. And becoming part of that group was really the best thing that could happen in that situation.”

Before inhabiting the old warehouse, a group of people with different backgrounds—including former inhabitants of other occupations in central Rio such as Chiquinha Gonzaga and Zumbi dos Palmares—started organizing themselves through regular meetings.

“I started participating in the meetings every Sunday over a period of five months. The first occupation took place at Cinelândia, in a building that’s occupied by the Manoel Congo group today. We were an organized group, without a name. The police arrived and evacuated the building within 24 hours. The same happened with our second attempt in Vila Isabel, North Zone. This is when our name, Quilombo das Guerreiras (Women Warriors’ Quilombo) was chosen, referring to the many female ‘warriors’ among the group members.”

In the early morning hours of October 9, 2006, around 120 families occupied a warehouse that had been abandoned by the Rio de Janeiro Docks Company for about 20 years. The occupation was successful, with families establishing a home and community over the following years.

Nilde says: “We managed to stay for eight years. This is where my sons grew up. It was a great building, with a marbled interior and large spaces. We put tons of work into the building. We didn’t have any water or electricity when we first entered. According to Brazilian law, every building must have electricity… And of course, [the government] didn’t do anything about it.”

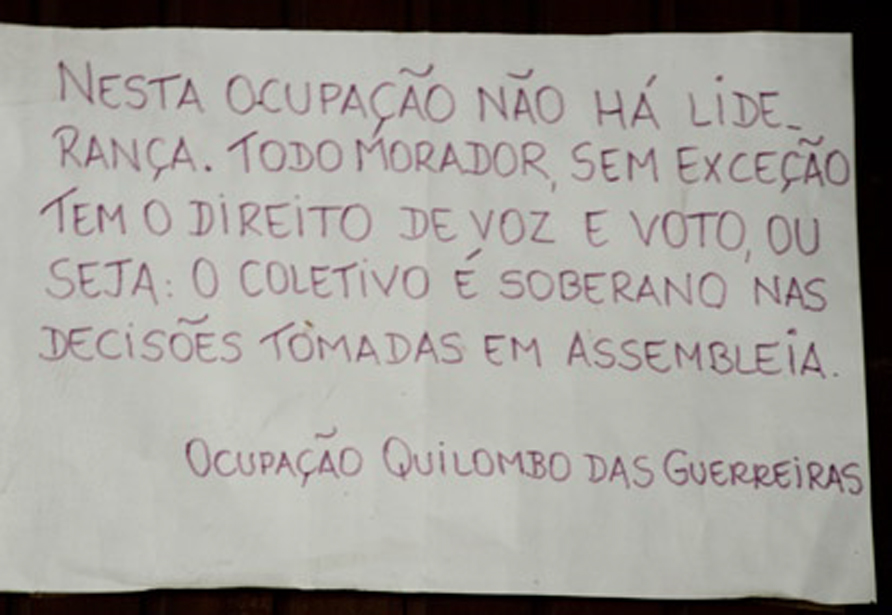

Nilde describes how the Quilombo das Guerreiras was more than just a housing project: “It was a dream come true. We had our very own theater, a classroom where children and adults were taught how to read and write, workshops to produce flip flops and shirts.” Communal tasks were organized and distributed among committees, with each group responsible for a different task such as water and electrical services, cooking, cleaning, and finance, among others.

In addition to providing a home and community for residents, the occupation was positive for the largely abandoned Port Region. According to Nilde, “the murder and assault rates in the area dropped by 80%” because more people were using the neighborhood’s streets.

There were many moments of tension and repression over the eight years, from power cuts and an irregular supply of food and water, to intimidation by port security guards and the constant presence of bailiffs delivering injunctions for repossession of the warehouse by the Docks Company. But the warehouse residents did not feel alone in their struggle to remain, says Nilde: “Everyone united to defend the right to housing. [We had] great support from social movements, including Center for Popular Movements (CMP) and the National Union for Popular Housing (UMP), as well as young professors and students. They supported us from the beginning. One day, they even blocked the door to prevent the police from entering, with all the residents inside.”

However pressure began to mount as the City intensified efforts to evict the region’s occupations. Nilde explains: “In 2012, the City, with the Porto Maravilha revitalization project in mind, evicted two unorganized squats in the Port area. They were thrown out like animals and placed in the empty warehouse behind the building occupied by the Quilombo das Guerreiras. No water, no light, no home, nothing. And that’s the moment when things got worse. Prostitution, drug trafficking, murder… a disaster. And the threats. It was very dangerous. The City started invading the building, putting holes in the walls, forcing us to leave… I was one of the first to go. I picked up the kids and rented a house in a community in São Cristovão.”

After a long struggle, in September 2013 the federal government signed a decree expropriating the building occupied by the ‘Guerreiras’ group along with thirteen other properties in the area, smoothing the progress of the Porto Maravilha development projects including Rio’s Trump Tower to be developed where Quilombo das Guerreiras was located.

Today, Nilde rents an apartment she struggles to afford in Santo Cristo in the Port Region with her three sons. Many of those who were forced to leave Guerreiras moved just down the road to the Quilombo da Gamboa, where a contract to start the development of 116 housing units was signed in July. As one of many who emerged from the eight-year Guerreiras occupation as a leader, Nilde serves as a representative of future residents of the Gamboa housing cooperative at events such as the contract signing. Construction on the Quilombo da Gamboa housing development is due to begin at the end of this year.