With less than 24 hours before the announced invasion and occupation of Rocinha by a combination of police and military forces, I made the mototaxi ride up the hill to visit the family of Seu José, whose house I stayed at various times in 2007, 2008, and 2009. A cloud settled in over the course of the afternoon, a kind of pathetic fallacy for the tempest brewing in the machinations of the political-military complex, to a backdrop of real estate values and international media attention.

The family had just returned from making a supply run, just like preparations for a hurricane or blizzard in North America – the essentials to ride out the storm, with the anticipation of spending up to three days without leaving the house. Gatonet (pirated cable and Internet) has already been cut, so while the rest of Brazil will watch breathless coverage on TV Globo starting live at 5am, residents of Rocinha will only have the sounds of helicopters, tanks, armored trucks, and maybe a radio broadcast, along with furtive peeks out the window.

Seu José and his daughter Walda were pensive and keenly reflective about the tumultuous events of the last week, which began on Sunday night with local boss Nem checking into Rocinha’s 24-hour clinic for reasons still undetermined – Walda counteracted the press reports of a drug overdose and said the gossip around the neighborhood is that it was pure stress. She was heading to work at 6:30am on Monday morning and nearly broke down in tears to see so many armed traffickers guarding the prominently placed clinic. Since that morning, she hasn’t seen a single armed trafficker. Even still, when the news broke on Thursday morning that he had been arrested, she couldn’t believe it.

The family lived through the killing of former chief Bem-te-vi in 2004 and they expect an easier go of it this time, hopefully no shots fired. But they reserve plenty of suspicion for the police – a known quantity – and the military – an unknown one – that will very soon make their presence felt. Seu José’s house has played host to foreign volunteers in Rocinha for social work or research for many years, and on several occasions (including one that I lived through in 2007), police incursions have resulted in confusion and a house-to-house search when a group of gringos who don’t speak Portuguese well are faced with an armed cop.

The family is still unconvinced that the police/military will stay after a couple days – an unprecedented occurrence since drug traffickers assumed control of Rocinha in the 1980s – and there is plenty of concern about what’s next in the event of a power vacuum. If they do stay, then the specter of what happened in the Complexo do Alemão – theft and harassment by state forces – is also unnerving. A few days ago, Walda wrote on her Facebook wall: “Mais na boa acho que a UPP não vai adiantar de nada, pq os maiores traficantes ainda estão por ai soltos, roubando de terno e gravata!!!” (On the balance the UPP isn’t going to change anything, because most of the criminals are free anyway, stealing in a suit and tie!!!)”

Seu José, meanwhile, reflected on his 41 years in Rocinha, having arrived in 1970 from the northeastern state of Ceará. He remembered when there was only one bar in the whole community – which now has a commercial presence larger than many small cities – and he walked around with the receipt from his bus ticket in his pocket. The police would stop young men to check if they had a work card, and if not throw them in jail. He kept his bus ticket as proof of where he came from in case he was deported back to the northeast.

He recounted bloody tales of police attacks on drug traffickers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and when he feels Rocinha is on the cusp of a real change, that means something. For good or for ill remains the question. As he puts it, “Everything irregular is going to stop.” That means that his pirated TV/Internet is gone, and I was asked for advice on which Internet provider to use. While the family claims they were satisfied with their pirated service, they are prepared to pay a little more and have a formal contract. Sky TV has been blitzing the streets of Rocinha to sign up residents now that their cable connections have been cut – it’s a sad commentary on Brazilian society that getting TV back is the biggest priority, but now a typical routine in newly-occupied favelas.

A silver lining for Seu José’s family has been the relative quiet since last weekend. The 24-hour cacophony in Rocinha has slowed to a murmur – don’t expect to hear a baile funk tonight on Rua 2, or tomorrow night in Clube de Emoções, or the pagode party where Nem gave his tearful farewell last Sunday. The bar on the corner that has been doing live forró every weekend at earsplitting volumes has also stopped. Pacification has sonic implications alongside the socio-political ones, undoubtedly. For this evangelical family, of course, they are just as happy to see the baile funk shut down, and wish it had come sooner so they could have gotten a better night’s sleep before the national college entrance exam a few weeks ago.

I bade them farewell and headed back down to the bottom of the hill, passing a usual Saturday afternoon’s business – bars doing a brisk trade in beers and billiards, stores selling clothes, crowds coming in from the beach, a stray barbershop or beauty salon – with one exception. Pirate CD and DVD sellers were fireselling their wares, laying out trash bags on the sidewalk that eager patrons were scouring for good titles. Everything must go for 1 real a piece as Hollywood movies, sertanejo albums, hardcore porn, and live funk shows are likely to be swept up in the same dragnet that is looking for guns, drugs, and cash. Piracy funds terrorism indeed.

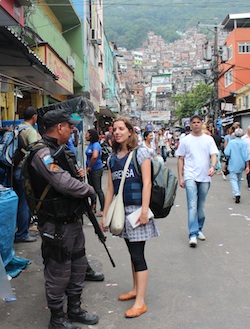

The entrances to Rocinha were choked with journalists, TV cameras, military police, and more Sky TV reps (the only, I might add, to actually walk into Rocinha rather than mill about at the bottom). The media spectacle of the war next door – Rocinha lying in the midst of one of Brazil’s highest concentrations of wealth and power – will surely keep eyes glued to the tube all day long from the safe confines of gated condos or summer houses. For the unlikely 150,000+ who are about to endure the next several days of armed military occupation, they’ll have to be content with whatever movies they scooped up from the camelôs.