Today, October 31, the United Nations invites individuals, communities and countries worldwide to celebrate World Cities Day. The annual event was developed in 2013 with the aim to “promote the international community’s interest in global urbanization” and highlight the importance of harmony among the city’s spatial, social and environmental aspects and between its inhabitants, a harmony that hinges on two key pillars: equity and sustainability. This year’s theme is ‘Designed to Live Together.’

Once Rio de Janeiro was awarded the 2016 Olympics Games in 2009, urban planning took on a new scale and significance for the city. In particular, Barra da Tijuca in the West Zone was to undergo substantial transformation for the 2016 Olympics, including the construction of the Olympic Park from scratch.

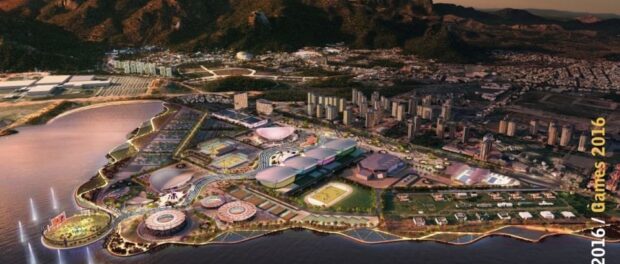

The winner of the design competition for the Olympic Park and ‘2030 Legacy‘ arena was the global infrastructure firm, AECOM. Its proposed design was chosen by the Rio 2016 Organizing Committee and the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB) with 2016 and 2030 visions:

As the images above show, AECOM’s plan for the Olympic park left a significant portion of the neighboring community of Vila Autódromo, labeled in the top left corner, in place. In other words, it was a plan for how the Olympic Park and the community would co-exist side by side.

However, despite the residents’ legal titles to the land (granted by the state government in the 1990s), the preservation of the community in the AECOM Olympic Park design (which was selected by the municipal government), and Mayor Eduardo Paes’ own insistence that “a city of the future has to be socially integrated,” Vila Autódromo has been targeted aggressively for near total removal. Due to evictions thus far, the neighborhood has shrunk by 83% in the last two years. Paes has repeatedly claimed that part of the community can remain, but a recent official Rio 2016 video appears to project the Olympic Park with Vila Autódromo completely removed.

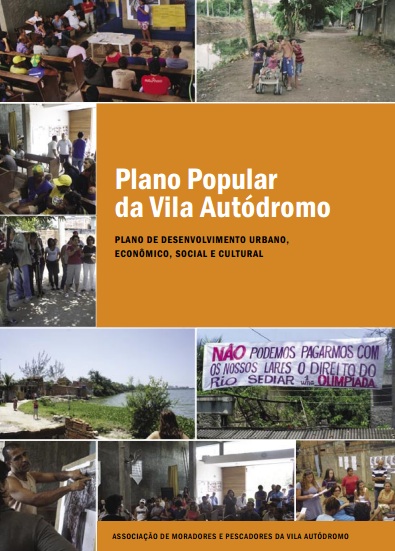

With many families against relocation to isolated public housing projects, residents came together with allies at two Rio universities to create an alternative vision for their community, expressed through an upgrading plan known as the Vila Autódromo People’s Plan. The People’s Plan, first presented to the government in mid-2012 and now in its fourth version, affirms the community’s commitments to remaining in place and to the preservation of the local lagoon environment. Moreover, the urbanization plans confirm the residents want to, and can, co-exist in harmony with the State, the construction of the Olympic Park, and the global community brought by the Olympics.

“Designing through participative process helps people come together around shared goals and visions, and promotes everyone’s equal access to services, jobs and opportunities.” – UN

A scan through the People’s Plan reveals that it aligns well with key elements of good design recently identified by UN Habitat Executive Director, Dr. Joan Clos:

- “Good design contributes to social integration, equality and diversity. Planning residential areas with different possibilities in terms of typology and price enables residents from different backgrounds and income levels to live together…”

Housing arrangements in the Vila Autódromo People’s Plan include the maintenance of limits to construction by the waterfront for the protection of the lagoon and for all vacant lots to be utilized according to housing priorities.

- “Good design fosters sustainable use of shared resources. Planning compact denser cities reduces the overexploitation of natural resources, and facilitates common living by enabling equal access to land, food and water for all.”

The environmental plans for Vila Autódromo include the recovery of the area around the Jacarepaguá Lagoon and the canal’s edge, widening the streets for water drainage, improved circulation, and the renovation of the park.

- “Good design inspires lively neighborhoods. Designed public spaces, parks, playgrounds, streets and squares filled with activities help create a vibrant public life for all residents.”

The People’s Plan addresses community members’ inclusion in the Family Health Program, as well as the construction of a day care center, a public school and new areas of sport and leisure.

- “Good design can make areas safer. Neighborhoods that remain active and lively at night, with commercial activities on the ground floors, pedestrian friendly well-lit streets and public spaces mean increased personal safety and security.”

In Vila Autódromo, cultural and community developments include the creation of a cultural center to host public events such as theater and music shows. A strategy to develop both internal and external communication and mobilization for the community was also part of the plan’s development.

However, neither its alignment with UN-Habitat ideals nor international recognition of the plan has prevented forced removals. Residents and allies have been forced to make a series of modifications to the People’s Plan to keep it up to date as evictions take place and the community shrinks:

Regina Beinenstein, Program Director and Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at Fluminense Federal University (UFF), explained how the People’s Plan had been modified by version three (image directly above) with respect to the demolitions that had occurred since the first iteration of the plan. As of version three, produced recently, 95 houses and lots remained. Incorporating the Olympic Park access roads the City has indicated need to exist in the region, Regina explained: “Where possible, the lots where houses remain, but which have an area less than 120 square meters, are to be expanded in order to improve [residents’] housing conditions.” For the areas that were empty following demolitions, and which will not be used for Olympic access roads, the proposal calls for the division of the land into 76 ‘lots’ to house combinations of two-story and single-family homes. Some lots would be set aside or maintained for communal purposes, including recreation spaces, the Residents’ Association, a community nursery, and sewage infrastructure. The proposal also outlines plans for improved and expanded water, sewerage and drainage systems. And finally, the version three image makes clear the importance of green space to community members.

However, following the recent sudden demolitions on October 23, the plans require further modifications. This time, Professor Beinenstein said, the residents have organized a list of around 50 families. According to resident Maria da Penha Macena, these are 50 families who are determined to stay and won’t take any form of compensation, as they believe their “house is not just a house, it’s a story…and there’s no price on that.”

Beinenstein explained that modifications will propose a new division of the land which maintains the homes of the families who will stay and will address the priorities of this group of around 50 families. The latest version is focused only on individual family lots, rather than previously proposed options for shared lots which are no longer necessary, and includes plans for a community vegetable garden and an area for a children’s park.

The day after the latest demolitions, Maria’s daughter, Nathalia Silva, was still able to think positively regarding the future. She said that what the community needs, more than just what they want, is urban reconstruction and basic infrastructure. She continues to see the benefits in a cultural center, a medical center and nursery for the future of the community. “These will not only help our community but surrounding communities—it will be of collective benefit,” she stated.

While Nathalia focused mainly on local aspects, her mother, a renowned activist in the community, gave a more global vision for Vila Autódromo’s struggle. Maria da Penha believes firmly that, in order to address local inequalities, everybody needs to work together to change government actions, not just in “her” country but around the world. In order to live together (in harmony), everybody needs to embrace this idea. She asserted: “Let’s change the world, not just one country. Let’s change the world!”

Both Nathalia and Penha agreed what the community deserves most is respect and honesty; at this stage the promises made by Mayor Paes seem far from reality and residents are forced to negotiate and revise their expectations every day. It feels like they have to “kill a lion each day,” Nathalia explained wearily.

Professor Beinenstien describes the updated People’s Plan as yet another “viable technical alternative which helps and works as a tool for the community to remain permanently.” With the ongoing revisions, the struggle to design and redesign the community in the hopes of living together with the Olympics continues.