This is the final in a series of three articles summarizing reports on Brazilian housing law, organized by the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice at request of Catalytic Communities. The second report, summarized in part below, was produced by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer US LLP. To read the actual report, click here.

As was covered in an earlier article on Community Land Trusts (CLTs) on RioOnWatch, market-rate housing by definition does not meet the affordability demands of the bottom socio-economic tier (normally 20-30%) of a city’s population, so transferring favela housing to the formal market will not address the needs of that group–it will only displace them, causing new favelas to form. We have thus been exploring alternative options to individual titling for guaranteeing long-term affordable housing and tenure to favela residents.

Community Land Trusts began in the United States as a model of land tenure that emerged from the civil rights movement in the South. CLTs have slowly gained popularity over the past decades, expanding dramatically in recent years. They have spread across continents and contexts, resulting in a plethora of rules and structures. Here we highlight select examples of CLTs and cooperative housing around the world highlighted in the Freshfields report, that could be informative models when considering the potential for Rio’s favelas to be titled collectively using a CLT framework or otherwise borrow lessons from cooperative housing.

United States: Champlain Housing Trust

CLTs in the United States have become more common as various forms of “third sector housing” have emerged aside from traditional private and public housing options. The Champlain Housing Trust (CHT) is the biggest of at least 240 CLTs in the U.S. and is located in Champlain, Vermont. CHT manages 2,200 apartments and oversees 565 owner-occupied homes. To support its members, it provides home purchase education, financial counseling, affordable energy efficiency services and loans for home repairs.

The CHT was started by a US$200,000 loan with the goal to increase the number of affordable homeownership opportunities, provide access to land for low-income residents, and promote neighborhood preservation and improvement. As a non-profit organization, the CHT serves residents whose income is no more than 80% of the average median income in that area.

Like many other CLTs, the CHT has a governing board divided in thirds and elected by residents: one-third of its membership is constituted by CHT residents; another third from surrounding communities; and the final third is comprised of municipal officials and a regional representative who are presumed to speak for the public interest (in other CLTs this final third is often comprised of technical specialists like engineers, accountants, planners, architects, social workers or lawyers). CHT’s particular governing board is made up of 15 people. Residents in the CHT obtain their land parcels through long-term ground leases for 20 years. They make a contract where they have full rights to the land, but only receive 25% of the appreciation of the land value if they choose to sell their property. This formula allows residents to regain their downpayment investment, the equity earned by paying off a mortgage and the value of pre-approved capital improvements, as well as 25% of the land appreciation value. It is meant to be fair, but also to allow the housing to remain affordable for future residents.

United Kingdom: London Community Land Trust (London CLT)

The London Community Land Trust is nearing completion of CLT homes in the space of the derelict St Clements Hospital in Mile End, East London and will be the UK’s first CLT located in an urban area (there are over 225 in rural areas). The trust is a non-profit open for membership to anyone who lives and works in London, with currently over 1,000 members. A number of private developers competed for the 4.5 acre parcel of land and it was only after previous failed attempts to secure the St. Clements site that the trust was eventually successful, partnering with a developer but maintaining a commitment to a community-led design process.

The London CLT is governed by rules that allow it to function outside of typical market pricing. It created a separate organization that is in charge of renting out the apartments each year and subsequently reinvesting the profits into the surrounding community. Under the London CLT model, all homes must be owned by the CLT in order to ensure affordability and these homes are only available to local residents. Rent rates must be decided by local income rather than traditional market rates.

The website of the London Community Land Trust explains that the campaign for a Community Land Trust first emerged around plans for the Olympic Park area, and claims the Olympic authorities have still not guaranteed the number of affordable homes initially promised during the bidding process.

Kenya: Bondeni Community Land Trust

In Kenya, land tenure issues are of high priority because precolonial methods of land tenure were more community-based than present day legal structures, which has led to serious conflicts over land rights.

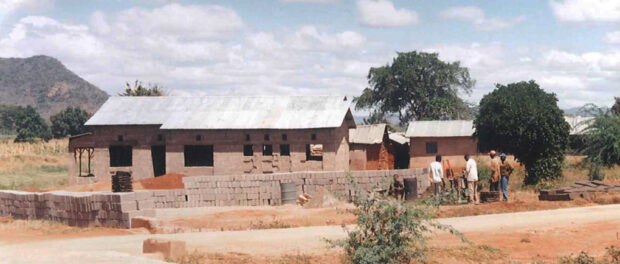

The Bondeni Community Land Trust was founded in the 1980s as a way to address the complex problem of urban settlements within smaller towns in Kenya. The implementation plan received substantial input from the community thanks to sustained mobilization by local residents who were determined to stay informed and involved in the process. Residents were identified, registered, and their needs discussed and prioritized, after which a committee was formed to represent them.

60% of households in the settlements own their housing structures, 30% are tenants and 10% of tenants live with the structures’ owners. The land is held by the community, but the local municipal council provides training and technical support for laying out sewerage and water pipes as well as an office for the residents’ committee. Residents own any developments on their own plots of land and can bequeath, inherit or sell them back to the CLT according to a specific resale formula.

The Bondeni Community Land Trust was funded by central government loans and a German institution, and was built on land donated by the municipal government. There are two main bodies that govern the CLT: the “society,” which is in charge of the day-to-day matters of the community-based organization, and the “trustees,” who are concerned with administrative matters such as issuing leases, determining fees for land rental, and making land use decisions.

Challenges include a lack of participation from female residents, despite the assurance of “reserved seats” for women in the governing bodies, and a lack of leadership training opportunities, literacy and language programs.

Switzerland: Cooperative housing, Zurich’s solution to a lack of land regulation

In Zurich, much like in Rio de Janeiro, there are no regulations on land prices or rent controls (which are a common strategy to contain rents from Washington, DC and New York to Los Angeles). To maintain affordable housing, the city either constructs and owns apartments for those in need (9,700 units), or subsidizes the construction of affordable housing by non-profit organizations (6,700 units). Most of the affordable units in Switzerland are instead owned by cooperatives (approximately 40,000 units). These organizations must be non-profits for residential purposes. Local governments must approve the rent rates and must have one representative on the cooperative governing board. The local states must also approve cooperative accounts and are responsible for disputes between tenants and co-op residents.

The federal government also plays an important role in funding cooperatives, regulates minimum space standards, and produces research on affordable housing. The National Association of Cooperatives allocates federal money to cooperatives as 10-year loans with a low interest rate. Recently, cooperatives that emphasize eco-friendly housing and energy conservation have received more funding. Three examples of cooperatives in Zurich are:

- Kraftwerk, created in 1995 by student activists who raised 20% of the money to fund the purchase of the site. There are 91 housing units, office units, two shops and a cafe on the property.

- Dreiecke, which was originally a city block seized by the government in the 1970s to construct a highway. When the highway proposal was not completed, local housing fell into disarray. The City wanted to demolish the properties, but resistance led to the creation of a CLT to preserve affordable housing for those who were squatting on the land already.

- Karthago is a cooperative at the site of a former Toyota showroom. A local group of activists set up the cooperative with the proposal to convert the building into 25 units of housing including a shared kitchen and dining area.

Uruguay: Nuevo Amanecer, housing and family cooperative and Ufama al Sur Cooperative

Uruguayan cooperative housing emerged in 1968 in the wake of a widespread housing crisis. The system is called a “mutual aid cooperative” and relies on the joint physical labor of its members, who must contribute at least 10% of the labor and capital to build the homes. Once the members have covered all the housing costs through their monthly payments, they become owners of the properties.

Nuevo Amanecer (NA) is located in Montevideo and consists of 423 households. The community was built on the outskirts of the city and men and women alike were each required to contribute 21 hours of hard work each week in construction. Homes were built to meet varying household sizes and needs, and the community built all of the infrastructure systems like water and electrical lines themselves.

The Housing and Family Cooperative (COVIFAM) is a member of the nationally-based federation of 300 housing cooperatives. Similar to Nuevo Amanecer, community members contributed to building the community. Each family has the right to use their home, but homes are owned by the cooperative. All decisions made in the cooperative are democratic through weekly meetings that continue even after construction ends.

Finally, the Cooperativa Ufama al Sur was created in 1998 by a local community-based organization. This specific cooperative is made up of Afro-Uruguayan women-headed households who live in an abandoned warehouse building that was sold to the cooperative by the municipality at a subsidized rate to create 36 apartments.

Bolivia: “Habitat para la mujer”—the Maria Auxiliadora community

Located in Cochabamba, the community-based and managed women’s housing project in the Maria Auxiliadora community emphasizes the role of women in leadership positions and decisions, so much so that the leadership position in the community is reserved for a woman, to be elected for a two-year term. The project was created in 1999 by a group of homeless female heads of household who obtained a loan of US$36,000 to finance the purchase of a 17 hectare piece of land. After land was divided, original residents had the opportunity to either build on the land or to leave the community after receiving a proper reimbursement for the land.

As of January 2014, a total of 152 houses had been built in addition to a range of community facilities, and 250 low-income families had acquired land there. Low-income families with children and particularly women-headed households who are homeless are given priority in the selection process. Gaining recognition, the Maria Auxiliadora community-initiated and managed projects have harnessed the support of numerous NGOs and have demonstrated that living conditions of low-income families can be greatly improved with little external funding, provided that the families’ own resources are mobilized and channeled through savings schemes, traditional forms of solidarity and mutual help, collective action and access to credit. Whilst it is important for the community to maintain autonomy and control of the process, the support of NGOs has been crucial to the success of the Maria Auxiliadora community.

Full Series: Brazilian Housing Law Memos

Part 1: What Does the Brazilian Constitution Say About Housing Rights?

Part 2: The Favela as a Community Land Trust: A Solution to Eviction and Gentrification?

Part 3: Community Land Trust Models and Housing Coops from Around the World