Today, November 20, is Brazil’s Black Awareness Day, a day to celebrate Black Brazilian history and resistance to oppression. While May 13 marks the adoption of the ‘Golden Law‘ that abolished slavery in 1888 with the signature of then Imperial Regent Princess Isabela, November 20 celebrates the death of Zumbi, the last leader of the Quilombo dos Palmares. Palmares was a runaway slave community that resisted Portuguese and Dutch military campaigns for nearly all of the 17th century. Though black social movements have celebrated the day since the 1970s, it was not officially added to the public school calendar until 2003, and a 2011 law signed by President Dilma Rousseff made Black Awareness Day an optional holiday at the municipal level. Today Zumbi is regarded as a national figure and Brazilians of all racial backgrounds celebrate the history of democracy and resistance that he embodies through marches, occupations, film festivals, music performances, seminars and parties throughout the month of November.

Talking about slavery around the celebration of Black Awareness on November 20 is not necessarily taboo, but it can reinforce the narratives that paint the black experience in Brazil as always about slavery. However, Brazilians generally and cariocas more specifically have rarely sought to contend with their history of slavery and racism. The myths of a benign, colonial slave society predicated on benevolent master-slave relationships and of 20th century racial democracy based on racial equality following abolition (i.e. since there was no institutionalized racism and segregation in Brazil like there was in the United States) have rendered slavery a historical fact that rarely receives national reflection.

With the US as paradigm of slavery and racism in the Western Hemisphere, little attention has even been paid to the Brazilian slave trade, despite its sheer magnitude. Brazil imported and enslaved nearly five million Africans, over ten times the number that reached the US and Canada and nearly half of the more than ten million people brought to the Western Hemisphere as slaves. Two million enslaved Africans arrived to the Americas at the port of Rio alone.

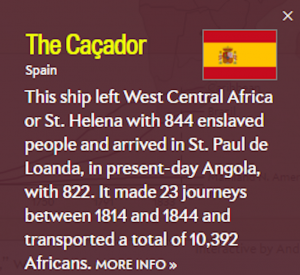

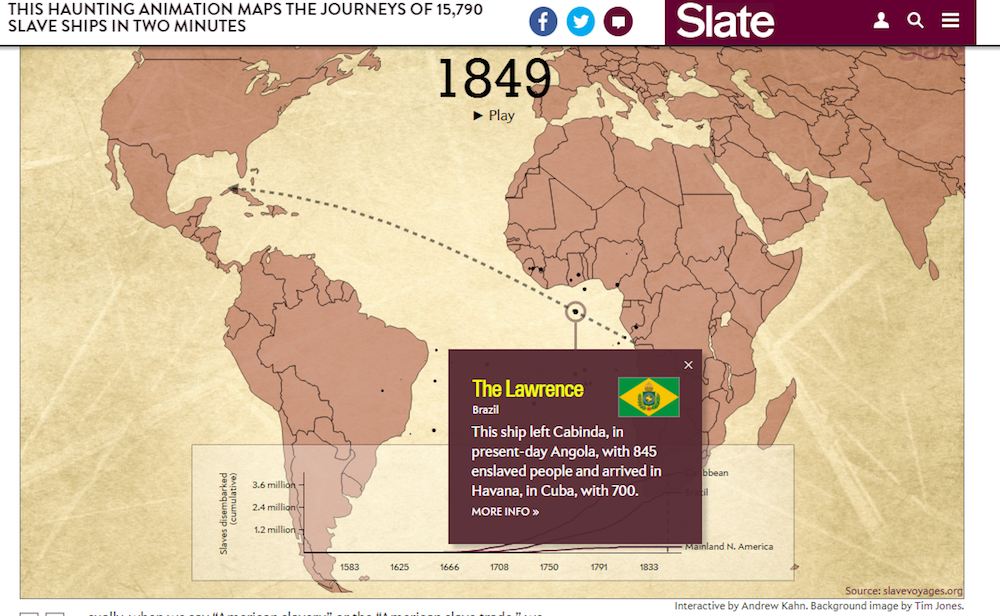

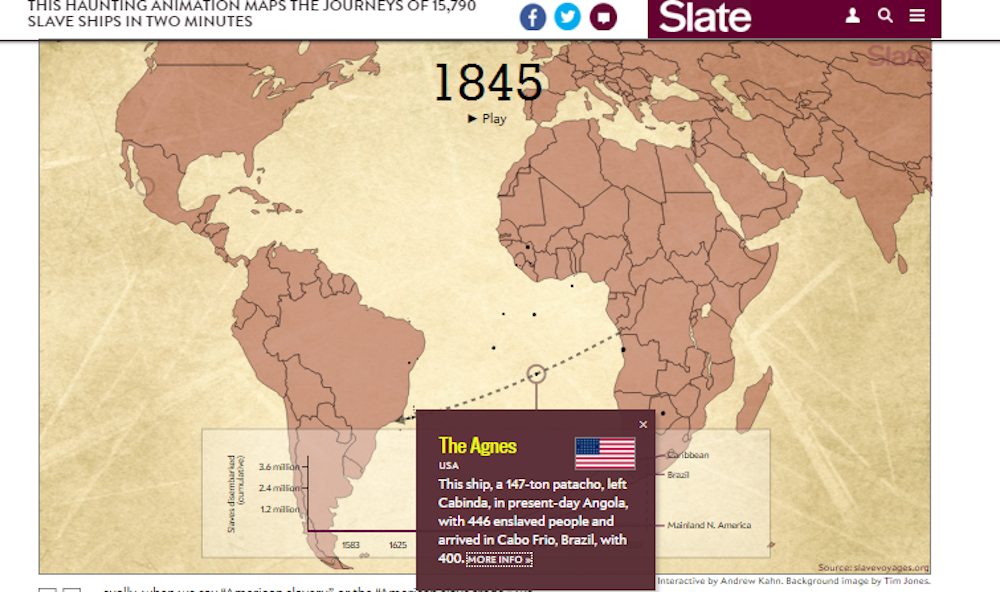

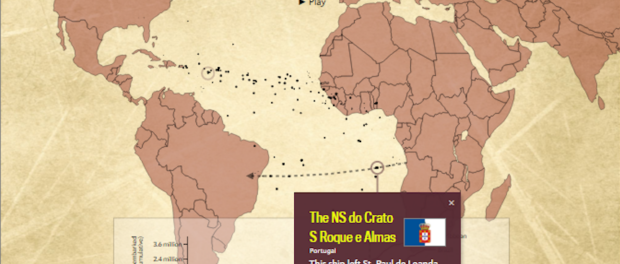

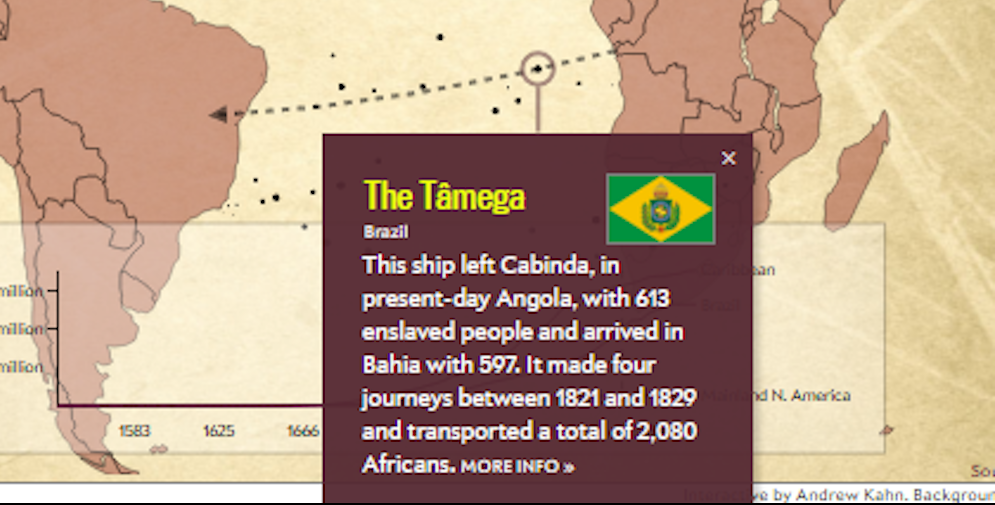

When speaking about large scale institutions and markets like slavery and the Trans-Atlantic Trade, it is easy to forget the individuals and small acts that comprised and sustained them. An interactive map produced by Slate, based on archives of slave ship manifests compiled by Voyages-The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, shows both the incredible scale and the minute, everyday-ness of the trade.

The map is a time-lapse of the trade from 1545 to 1860, representing, as the byline succinctly and powerfully puts it, “315 years. 20,528 voyages. Millions of lives.” Each dot is one voyage and the size of the dot represents the number of enslaved people forced to endure the Middle Passage. By pausing the map and clicking on a dot you can learn details about that particular voyage—the crew’s flag and state affiliation, route, the number of other journeys the ship made, the number of people who disembarked from Africa, and the number of enslaved people who actually survived the journey to the Americas.

You can also note geopolitical and national trends related to the slave trade. Portuguese and Spanish vessels dominated the early years of the trade, with hundreds of ships going to ports throughout the Caribbean and Cartagena in present-day Colombia. As European colonizers—primarily Dutch, French, English, Spanish and Portuguese—vied for dominance of industries like sugar, cotton, and coffee, their fortunes were increasingly linked to their ability to monopolize the slave trade.

Small details like the ships going to Europe serve as a reminder that chattel slavery was not only an institution of the Americas, but also one of European states and empires. The nature of these empires even saw slaves being sent from the Americas back to Africa. In the Portuguese Empire, banishment to other colonies was a common punishment. A 1749 Royal Proclamation prohibited even free blacks and mulattoes from dressing like whites and suggested exile to São Tomé as a suitable punishment for repeat offenders.[1]

The Portuguese Empire in Africa, coupled with the favorable trade winds, made the importation of enslaved Africans to Brazil relatively cheap. Decrees throughout the colonial period implored slave masters to actually feed their slaves or at least allow them plots of land to grow their own food, as many owners made the calculation that simply importing new, healthier people could prove cheaper than taking care of their slaves.[2]

A common 17th century refrain in Brazil, “without sugar, no Brazil, without slaves, no sugar, without Angola, no slaves,” speaks to the entrenched political, economic, and cultural early links between Brazil and Angola. However, routes changed as sugar production in the Northeast was replaced by goldmining and coffee production in the South, making Rio rather than Salvador in Bahia the Brazilian port through which most Africans entered the country, and at times shifting the trade up Africa’s Western Coast to present-day Benin and Nigeria.

There is a dramatic drop in the number of ships going to the island of Hispaniola following the end of the Haitian Revolution in 1804. As European power waned in the hemisphere following the independence movements of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, ships from Brazil dominated the trade. This was especially the case following Britain’s attempts to abolish the Trans-Atlantic Trade. Though Brazil passed laws ending the importation of enslaved Africans, they were “for the English to see,” with over a million people imported between 1826 and 1850, the height of Britain’s ideological and naval campaign against the trade.

The significance and legacy of the slave trade and slavery is emphasized by black musicians and activists. O Rappa’s 1994 song “Todo camburão tem um pouco navio negreiro” (“All police-wagons have a little bit of slave ship”) decries the racial profiling tactics of police. Similarly, the lyrics to Emicida’s recently released “Boa Esperança” (Good Hope) symbolically link favelas and slave ships while the video depicts a modern day revolt. Just as the slave trade operated on a perverse ideology that rendered black lives dispensable and disposable, young black men in Rio are routinely the victims of police violence, comprising the majority of the 1,519 police killings in the last five years as documented in a recent Amnesty International Report. Raull Santiago of Coletivo Papo Reto has frequently referred to favelas alternatively as senzalas (slave quarters) due to the exploitative relationship between the city proper and favelas, and as quilombos (run-away slave communities) due to their connection to a long history of territorial and emancipatory struggles.

[1], [2] Conrad, Robert Edgard. Children of God’s Fire: A Documentary History of Black Slavery in Brazil. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

Stephanie Reist is pursuing both a Masters in Public Policy and a PhD in Latin American Studies at Duke University. In Rio, she worked as a Felsman Fellow at Projeto Raízes Locais, a community-based project run by Associação Terra dos Homens, in Mangueirinha, Duque de Caxias. Her research looks at center-periphery dynamics, belonging and citizenship, and land rights.