Wednesday marked the launch of the publication of urban mapping done by more than 30 women in the Caju and Manguinhos favelas in Rio’s North Zone with guidance from well-respected historic NGO FASE, the Federation of Organs for Social and Educational Assistance. The release of the publication, titled “Urban Development and Institutional Violence: The Impacts of the Militarization of the City on the Lives of Women,” marked the culmination of a two-year process.

The goal of the program was to give women an opportunity to talk about the ways they experience violence daily and to map out the communities as a form of resistance.

The communities of Manguinhos and Caju are close geographically, but have different experiences with violence in the community and between the police and residents. Manguinhos, a favela of around 50,000 people, was founded more than 100 years ago and occupies a central location in the North Zone of Rio. Caju is a neighborhood of around 20,000 residents located near Rio’s Port Region and was once a vital part of the imperial city of Rio, but has since become neglected by the city and suffers from garbage dumping in the area.

“You know you have arrived in Caju by the smell,” reads one quote from the final document.

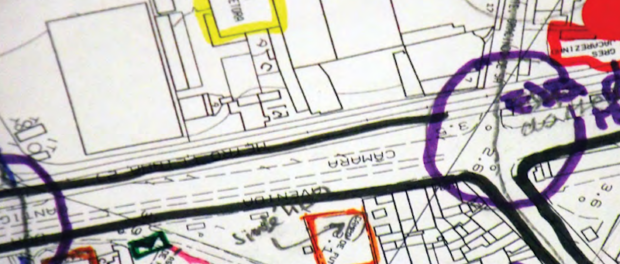

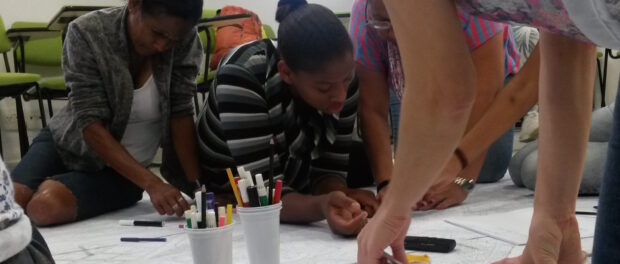

The production of the maps, which involved reflections, six workshops and discussion space, allowed the women to form a group in solidarity to discuss daily violence and its effects, such as the loss of their children or encounters with the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) installed in 2013. The process gave the women an opportunity to express their discontent with the treatment of their neighborhoods by the authorities.

“It is not in the interest of the government for the favela to have memory,” explains another quote from the women.

Although the women explicitly acknowledged that these maps were not meant to be holistic narratives of the communities, merely their perspectives and experiences, there were common themes that emerged from the workshops.

A sense of abandonment, the insecurity within the communities, and the feeling that the government only uses the neighborhoods to “showcase” certain projects were strong throughout the discussions. Many women felt their communities have many important assets within them, but many do not function well because the government has neglected them. When resources are designated to these communities, the women felt the lack of execution made clear these were false promises.

“The rival factions impede the circulation of people living in the communities,” said one quote highlighting the insecurity that many of the women feel.

Specifically within Caju, themes of false promises by the government, the conflicts with the UPP, and large amounts of trailers and empty shipping containers were brought up many times. For the women in Manguinhos, conflicts and discontent with the UPP and the lack of freedom to move around the community for their children were common topics.

“Manguinhos is fire and ice,” said one quote in the final document, encapsulating the emotional process of creating these final maps.

The creation of these maps signifies more than simply creating drawings on paper. The workshops strengthened the solidarity and networks among the women, who are often the most active in fighting for justice and peace within their communities. The women had to work together to discuss how to label each space within the community and come to consensus with what colors to use to identify them.

Although the main objective was to map the experiences with violence in the communities, the process of mapping uncovered other topics and issues like housing, health, racism, gender and education.

One resident of Manguinhos summed up the process of mapping by saying, “In the past, we could not talk about certain subjects… [but] today we can get together, participate in movements and shout.”