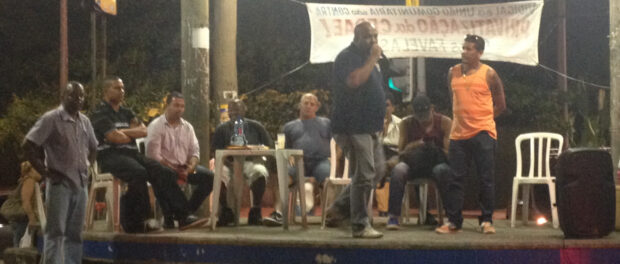

Around 100 people met at the base of Vidigal on Wednesday, February 17 to voice their discontent with the state’s impending decision to privatize the water and sewage management utility, CEDAE, in the favela. Convened by the Vila Vidigal Neighborhood Association, the meeting not only brought together leaders from Vidigal, but also united leaders from a number of South Zone favelas, including Santa Marta, Rocinha, and Tabajaras. These other leaders came to Vidigal by way of the Community Union, an inter-community association of leaders from over thirty favelas formed in 2014 to advocate for better public policies in their communities. The meeting in Vidigal was one in a series of meetings the Community Union is conducting in favelas throughout the South Zone on the possible water privatization, and came following meetings in Santa Marta and Morro dos Prazeres.

The community leaders claim that the privatization of CEDAE is happening first in favelas where Pacifying Police Units (UPP) have been installed, and that it acts as a form of gentrification-facilitator, pushing residents out of their properties without official evictions. This is particularly troubling since the UPP policy itself is already linked to price hikes and gentrification. André Santana from Morro do Andaraí said, “My father’s struggle was against eviction. They successfully fought against many people being removed. And their fight will not be in vain.”

While the claim that the privatization of CEDAE is only currently happening in these South Zone favelas is unconfirmed, community leaders highlighted that the de facto effect of increased utility bills has the potential to have a large impact on low-income favela residents. In particular, they emphasized how detrimental the privatization of the Light electricity utility has already been for the community.

Community leaders from Vidigal described residents receiving monthly Light electricity bills of R$800, when many make about that salary per month. Zé Mario, president of the Santa Marta Neighborhood Association, relayed a story of a man who had a bill of R$1198 and arrived at the association downtrodden, explaining, “I have to leave the favela.” Local activists produced a film about his case.

Such stories of abusive billing by Light, and even more extreme cases, have been building since Light was privatized in 1996. A study of Light bills in Chapéu-Mangueira carried out by Alexandre Mendes, a law professor at the Rio de Janeiro Pontifical Catholic University (PUC-Rio), found that “Light has used a strategy after the entrance of the UPPs to stabilize consumption ceilings in bills, and gradually raise them,” charging residents fixed rates that do not necessarily correspond with consumption.

In the case of the water and sewage treatment services, as with electricity, there has already been some disconnect between consumption and cost. Before the UPPs were installed, many residents individually sourced water in informal, artisanal ways. Residents sourcing in this way were accustomed to water irregularities, but now in part due to the water crisis in Rio, even CEDAE water services are irregular, despite coming along with bills which now threaten to rise with privatization.

Sewage treatment services also suffer from irregularity under CEDAE. Santana explained at the meeting on February 17 that Morro do Andaraí had been without sewage treatment services for about two weeks, and that the CEDAE sewerage coordinator responsible for that community had posted an apology for the service gap on Facebook.

There has been some positive news since the meeting: it has been ruled that CEDAE can only charge the fee for sewage treatment in cases where it indeed collects, treats, and sends sewage to its designated destination. If the ruling is properly implemented, this should help communities avoid fixed rate bills that are not tied to services provided, though it does not cap costs when services are adequately provided.

While speaking out against unreasonably high utility bills that do not correspond to usage, speakers at the meeting also stressed the need to do away with the myth that favela residents do not want to pay for water and other services, explaining instead that they just want to pay a fair price.

Santana connected the possibility of a subsidized rate for favelas to the need for public investment in favelas overall: “The favelas need public policies, schools and hospitals.”

With pacification, formalization of utility services has been touted as a form of social inclusion by public authorities, but integration into market-based services has often preceded investments in education and health. Alluding to the upcoming 2016 Rio Olympics, vice-president of the Vila Vidigal Neighborhood Association, Sebastião Aleluia said, “The better Olympics would be one of hospitals and schools [competing to be best].”

Finally, community leaders called for broader civic engagement. Vila Vidigal Neighborhood Association president, Marcelo da Silva, asserted to the crowd: “This bill will arrive individually to each one of us. It’s not enough to complain at the bar, in line for the bus, the moto-taxi, on Facebook.” The leaders encouraged residents to come together before authorities take action. Santana reminded residents: “It’s good to remember that everything is politics, from the price of your beer to the Light bill and when you’re watching your novela.”

The next steps are for meetings to continue in other favelas that participate in the Community Union, and to potentially articulate collective direct action across these communities.