The number of public schools occupied by students more than doubled in just four days, with 45 schools occupied by Friday April 15. On the same day, Rio de Janeiro’s state Education Secretary Antonio Neto recognized the legal legitimacy of the occupations and resolved to begin fresh negotiations with the students, after Judge Sérgio Seabra Varella ruled on Monday April 11 that the occupation of Mendes de Moraes school on Ilha do Governador was lawful.

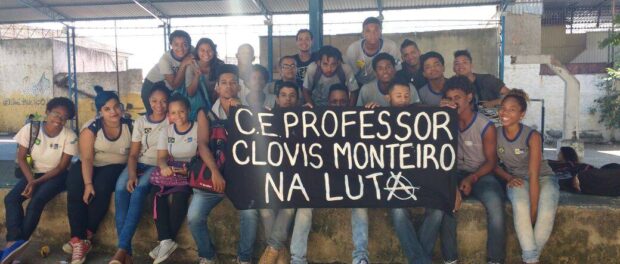

The numbers of occupied schools is currently fluctuating, with state teachers’ union SEPE claiming 64 schools across Rio de Janeiro state are occupied, while Rio city-based activists have publicly acknowledged 60 and Rio’s state education secretariat recognize 55 occupations.

Disputing the legality of the schools’ occupations had been the government’s most severe critique of the movement until Varella’s decision, but government figures also attempted to undermine the legitimacy of students’ complaints by claiming that students’ issues were specific to their individual schools.

In an interview on Rádio Globo with Mendes de Moraes student João Victor on March 29, Neto alleged that the complaints were only applicable to Mendes students and proceeded to insist their demands could all be met “if they spoke directly to their school director.” He also claimed that students had not yet tried to speak directly with him about the issues they were facing, but admitted less than ten minutes later in the same interview that his department had spoken to students on the first morning of the occupation.

Some students occupying their schools also reported threats, intimidation and aggression from Military Police as among the first official responses. Police facing legal gray areas attempted to enter schools, including the Chico Anysio School in Tijuca on April 8 and Mendes in its first days of occupation.

“They entered by force, they came here in the auditorium with handguns and M16s, trying to find a motive to do something and saying students occupying were not the majority,” said Alan, an 18 year-old Mendes alumnus supporting the occupation.

“They didn’t see the occupation as legitimate, as something with good intentions. But they knew they could not be here with firearms and without a warrant, and we prevented them from entering on the third day [of the occupation].”

Students from Chico Anysio say the Military Police’s tactics have evolved in the last week, calling their actions towards the students “psychological pressure.” Cecilia, 17, spoke about how police had telephoned parents of the students occupying the school and told them they would be arrested. They then proceeded to attempt entry by force, and stood outside the school gate with firearms and “enormous guns” while three students remained alone inside during the occupation’s first hours.

Some students have also faced threats from other parties. Laetitia, a 17 year-old student from Gomes Freire school in Penha, told RioOnWatch that in the first two days of their occupation, an individual claiming to be from Rio state’s guardianship council entered and assaulted some of the occupying students.

“He came without identification, we don’t know if he was from the guardianship council or not,” she stressed, “but he entered by force and beat two students.”

With only 20 to 30 students sleeping in many of the occupied schools and numbers reaching around 100 students occupying in the daytime, officials have also sought to claim that the movement is undemocratic and that the occupying students do not represent the majority, despite all students being invited to vote on occupations before they happen.

“There are 2,300 students registered here, but it’s wrong to say that their absence means they are not in support of the movement,” said Alan.

“Many students are minors, and most can’t stay all the time. And there are some whose parents will not let them come because they know what has already happened and fear for their children’s safety.”

Students occupying their schools have also received support from their wider communities, including donated food, cleaning materials and access to Wi-Fi from neighboring residents. Students in many schools have received advice from human rights lawyers, verifying the legality of their occupations. With the aid of community members, students have also been hosting debates, activities and alternative classes on everything from the military dictatorship and feminism to muay thai and yoga.

“The community is really supporting us,” said Pedro, a 16 year-old student at Chico Anysio. “They saw the police vans outside the school on the weekend, and when people were passing by they asked how they could help, what we needed here.”

There is also demonstrable online support for the movement, with more than 30,000 likes for the activist Facebook page reporting the movement and almost 9,000 likes for individual schools’ occupy pages.

Occupying students acknowledge that protest movements always face some opposition, but are hopeful for success in the near future. With the movement growing, students and teachers have been able to express solidarity with one another and cast off previous accusations that teachers were manipulating students.

“It’s more than a question of just salary,” said Mariana, an educational psychology professor from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), while visiting Mendes. “It’s much more than that: it’s the lack of necessary studying and working conditions, the employees fired without receiving their wages…”

Students, too, view the occupations as about more than just their own personal situations or the schools they attend. Cecilia is in her final year at Chico Anysio, as is Laetitia at Gomes Freire.

“It won’t make that much different for us, in our final year,” said Laetitia. “But it’s not for us. It’s for the future.”