From April 2 through May 21, the Centro Municipal de Arte Hélio Oiticica (The Hélio Oiticica Municipal Art Center) is hosting the exhibition ComPosições Políticas: Outras Histórias do Rio de Janeiro (Political ComPositions: Other Histories of Rio de Janeiro). The exhibition features the work of 12 artists from different parts of Rio: Hevelin Costa, Leila Danziger, Lívia Diniz, Guga Ferraz, Naldinho Lourenço, Josinaldo Medeiros, Davi Marcos, Wagner Morais, Rafucko, Aleta Valente, Francisco Valdean and Gê Vasconcelos.

The 19 works that make up ComPosições Políticas take as their aesthetic and conceptual starting point recent images from Rio’s favelas and peripheries that circulated widely on traditional and social media—like the photo of the car with 111 bullet holes after Military Police in Costa Barros gunned down the five young men inside who were on their way out to eat. The works question how these images both make visible and render invisible the everyday lives of favela residents who must contend with issues of police violence, poor public services, racism, marginalization, and stigma. Of the 19 works, only three are considered finished by the artists themselves, making the exhibition ever-changing.

The exhibition emerged from the artists’ four week residency during March at the Galpão Bela Maré in Complexo da Maré in Rio’s North Zone. There they worked both individually and collectively to develop their pieces, while also living with local artists and immersing themselves in Maré’s strong history of community organizing and culture production. Families who had lost loved ones to police violence also came and spoke to the artists, allowing those who appear in these highly circulated images to work with the artists as they reflected on issues of collective memory, bearing witness to atrocities, rights to the image, and self-representation.

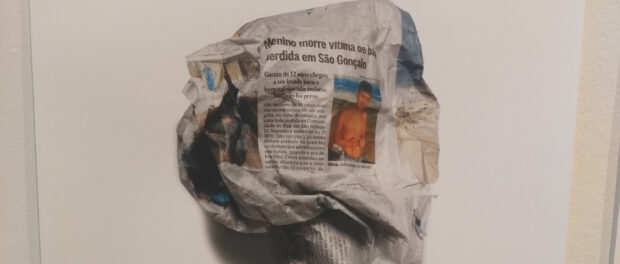

Leila Danizinger’s piece, Para-ninguém-é-nada-estar (For no one it’s nothing to stay) includes time stamped photographs of crumbled up newspaper articles with headlines announcing another victim of police violence, inviting the viewer to reflect on both the ubiquity of such tragedies and the ephemeral context in which we consume and discard them.

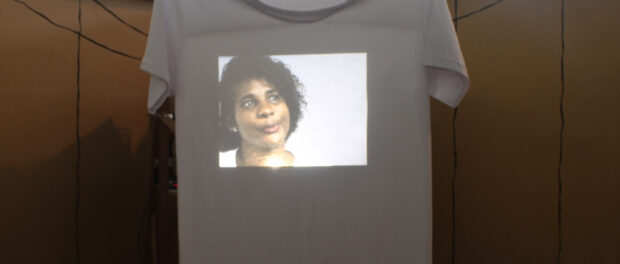

The forgotten headlines juxtapose Wagner Novais’s installation Saudades eternas (I’ll Miss You Forever), which speaks to the grief that families must endure for the rest of their lives after the loss of a loved one to state violence. Composed of t-shirts with the faces of victims of police violence hung on a laundry line, a banner with the five youths from Costa Barros within the Olympic rings that reads “Rio, Champion of Killing Indigenous, Black, and Poor People for 450 Years,” and a video of mothers telling the stories of their sons’ last day alive projected onto a plain white t-shirt, Saudades Eternas uses the image of hanging laundry to highlight that state violence is an everyday experience for many that is part of the historic fabric of Brazil.

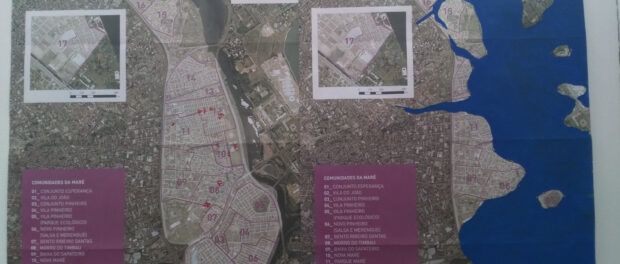

The works also explore how we define and are defined by urban space. Guga Ferraz’s Até onde o mar vinha, até onde o Rio ia (Till where the sea used to come, till where Rio used to go) uses a painted over official map of Maré to show how people have changed the physical landscape of the city.

Hevellin Costa’s video installation Segundo o corpo: em trânsito (According to the Body: In Transit) features four monitors that display videos from four cameras that he attached to his body during his four hour round trip daily commute on public transportation underscoring the physical toll that many Rio residents experience while navigating increasingly longer commutes.

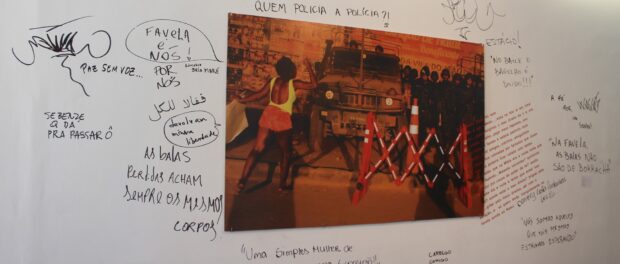

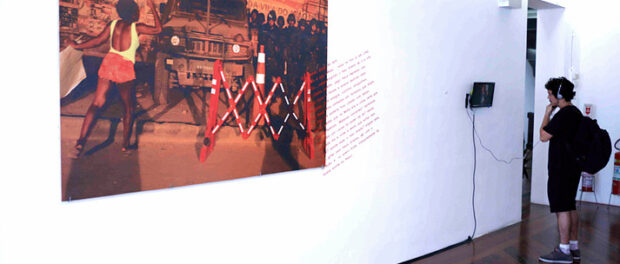

While many of the people in the original images are victims of violence and can thus no longer speak for themselves, Naldinho Lourenço‘s Dani features the striking image and text of Danielly Cantanhede protesting in front of police. Danielly’s thoughts from that day appear in red letters over a corner of the photo. Coupled with her dynamic stance as she addresses the police, the text gives the still photograph an almost audible quality, allowing Dani’s voice to continue demanding her rights: “Peace without a voice is not peace, it’s fear! This woman in the photo above is me. I was exercising my right to come and go; I am a citizen, I work, I pay my taxes, I’m black… I live in a favela and I was demanding more respect.”

Viewers are also able to add their own messages to the white wall around the photo, something that Danielly herself took advantage of when visiting the exhibit to remind the viewer that the gallery is also an elite space that has also ignored and silenced the voices of the marginalized: “A simple woman from the favela in an exhibition, my name is favela!”

The issue of self-representation came to a head with the work of satirist Rafucko. His MonstruáRio 2016 piece, conceived as an anti-souvenir shop that sells images that commemorate Rio’s human rights abuses, has been accused of racism by some black activists and their allies. Among the anti-souvenirs are: a toy car with 111 holes in it sold for R$111 recalling the tragedy in Costa Barros; “Apartheid Sandal” with an illustration of black men lined up to be frisked against a city bus, a “stop and frisk” tactic the city has used against young black men taking buses from the North Zone; and postcards with small pieces of brick from Vila Autódromo–the community that has been systematically removed to accommodate the 2016 Olympics. Activists took advantage of the exhibit to launch a widespread debate about the trivialization and monetization of the real experiences of Rio’s black residents, who are disproportionately the victims of state violence in what many believe is a genocide.

The diverse exhibition taken together invites the viewer to think critically about the images that we view, like, share, and comment on, asking: “How do we avoid the deactivating distance that often yields to the temptation to convert horror into spectacle?”