Nestled today in the shadow of Christ the Redeemer, the Horto community in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro was founded by workers of the Botanical Garden, established in 1808, who were given permission to settle on the land adjacent to the park with their families.

However, the history of the favela there does not start then. The first people who lived permanently in the area were indigenous slaves in the 16th century, who were used as labor on nearby plantations. Unfortunately historians still lack information on whether the land was settled by indigenous Brazilians even before the colonial period.

Emerson de Sousa, coordinator of the Horto Museum, shows visitors the oldest surviving building in Horto, built by indigenous slaves. Estimates suggest it could date back to the first sugar cane plantation in the area, which was established in 1575.

Emerson also points visitors to a book of great importance to the community, published in 2005 and titled Cacos de Memória – experiências e desejos na (re)construção do lugar: o Horto Florestal no Rio de Janeiro (Shards of Memory – experiences and desires in the (re)construction of place: Horto Garden in Rio de Janeiro).

In 2001, as part of a collaborative project called Nossa História (Our History) with the NGO Ler e Agir, Horto residents began the process of revitalizing the role the community’s history plays today. Oral history classes were given to young people in the community and, armed with this knowledge, they interviewed some the oldest community members in an effort to rebuild knowledge and give visibility to local culture.

The project resulted in a documentary and the Cacos de Memória book, which contains the testimonials and memories of 30 of Horto’s oldest living residents. Below, a sample of quotes from the book demonstrate the vibrancy of historic knowledge, both recent and old, among the older residents and now the youth who interviewed them.

Quotes from the book demonstrate that the neighborhood’s slave origins still influence daily life in visible ways.

“In the past this area here [Morro das Margaridas, in Horto] was a kind of slave quarters. The house here was called a senzala, that tall house where I lived. It was only one house, that was divided. The workers needed to live closer to their work, so the house was shared between four or five workers’ families.”

– Sr. Paulo Antunes da Fonseca, 60 years old

“Here at home we were always treated with herbs. Any problem with the liver or stomach, Mom always knew what herb to use. This was passed down and it passed down to me. When I have a problem with my liver, I don’t think about taking chemical medicines, I take boldo. There are a lot of people here who ask me and I give them the recipe. I get brejo, quebra-pedra, they drink the tea and feel better. Everything that we use is here, they were brought over by African slaves. They brought over roots and planted them here. Around here there are lots of plants that come from Africa.”

– Sr. Ismael Rego de Carvalho, 66 years old

After its stint as a sugar cane plantation, the land became a gun powder factory before the Botanical Garden gave permission to its workers to build their houses in the area that is now Horto, so they and their families could live closer to their place of work.

“The Director of the Botanical Garden allowed all our descendants to live here. Only the park workers lived here, only the park workers. There was a storm that knocked down some eucalyptus trees. That was where the workers took the wood from to make their houses. The director ordered the tree trunks be sent to the Botanical Garden and he gave everyone wood to make their houses. […] So it was the Director of the Botanical Garden himself who gave us the right to live here. No one invaded here.”

– Sra. Elza Maria de Souza, 73 years old

Horto also has strong musical roots, and many residents remember the samba played by members of the community, especially in Carnival blocos.

“Here during carnival we had rival blocos: people from Horto wouldn’t go to Balança, and vice versa, because of the bloco. It was a big rivalry, like Vasco and Flamengo. But there was no fighting, there were just arguments about the samba, about which one was better than the other. We always had this amazing open samba with the people. They take this kind of thing very seriously during Carnival.

– Sr. Bernardo Marcello de Sousa, 82 years old

Unfortunately, like many favelas in Rio de Janeiro, Horto has faced threats of removal over the years. One resident remembers Sr. Luighi Schicarino (Lili), the first person in the community to fight the threat of eviction, when a condo development was planned for the area in the 1960s.

“If it weren’t for Lili there wouldn’t be anyone living here. Lili was the one who took the lead, stopping everything here from being demolished. I don’t know how he managed it. I never participated actively. I know that he helped a lot. People who couldn’t pay taxes, he would pay for them.”

– Sra. Ruth Batista de Almeida, 76 years old

The current Horto Neighborhood Association, founded in 1982, continues the community’s fight to resist removal.

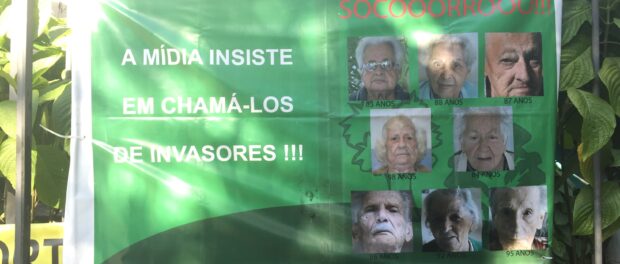

“What is happening now, this madness, is that they keep wanting to throw people out on the street. They keep on with this shamefulness, saying we are squatters. People who have lived here for around 100 years. That’s what hurts. Ah, you’re always worried! I think it’s a great social injustice to force people out of their homes, of their habitat, and send them to any old place. It’s horrible!”

– Sra. Cecília da Rocha, 70 years old

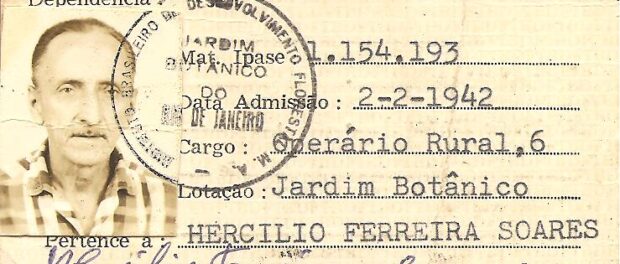

The Horto Museum has collected historical documents to build evidence that residents of the community have the right to live in their homes, a right they have maintained since the 1800s.

Despite this, the future of the community remains uncertain. In March of this year Brazil’s Environment Minister, Izabella Texeira, together with the President of the Botanical Garden, announced the removal of 130 families from Horto, apparently to expand the area of the Botanical Garden Research Institute.

However, the community is determined to fight the eviction threat as it has been doing since the 1960s.

The slogan “Horto: History with Roots” was prominently displayed at one of the community’s most recent protests. The community remains committed to celebrating its unique history and using this strong sense of heritage and historical rights as a tool in the fight against eviction.