In the early 90s, Brazil was full of uncertainties. Rampant inflation stole the dreams of many, the president had just resigned because of an impeachment process and the recently replaced government was trying to implement changes in the economy with a new currency–the real. In Rio de Janeiro, specifically in the North Zone of the city, families in neighborhoods such as Pavuna, Guadalupe and Costa Barros decided to build a new future. They were tired of the rents and the lack of opportunities. Children could be seen sliding on toboggans down the mud slopes, which was their little piece of land. Men, women and children armed with ropes and wires participated in marking their pieces of land. Often, families were forced to rotate vigils on their piece of precious land to avoid occupation by others. Over time the improvised wooden structures were substituted with brick houses, and now, almost thirty years later, the Complexo do Chapadão which was a dream of a better future is seen as one of the most problematic favelas in the entire state in terms of public security.

Comprised of sixteen communities and located in the North Zone of Rio, Complexo do Chapadão features regularly in crime reports. According to security specialists, it is considered the general headquarters for Rio’s oldest criminal faction. This occurred after the army occupation and installation of Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) in Complexo do Alemão.

Among the many cases of violence in Complexo do Chapadão to have been widely reported recently is death of taxi driver Jorge Fernando Souza. According to police, the victim was an ex-soldier who was confused for a police informant. The young man was tortured before being executed.

Statistics from the Institute of Public Security (ISP-RJ) show that violent crime is on the rise in the city which will host the Olympic Games in August. In 2015, the state of Rio experienced the worst in 23 years with regards to cargo theft, and 2016 the situation is on its way to surpass this. Just in the first trimester of this year, an 11% increase was registered above the statistics of the same period the previous year: 1,988 cargo thefts were recorded compared to 1,790 recorded in the first three months of 2015. The numbers for violent deaths are even more alarming. In 2015, close to 75% of men killed by the police in the city of Rio de Janeiro were black or brown. Of the 232 homicide victims killed during supposed confrontations with police, close to 25% were between the ages of 18 and 29. In Rio, almost half of the victims were dark skinned (48.5%). Of the total deaths in supposed confrontations with police, close to 28% were black. Of the more than 600 deaths officially caused by the police in the entire state, almost 30 were minors.

In all of these statistics, the Complexo do Chapadão region has the largest number of occurrences called autos de resistência [the term for deaths caused when suspects resist arrest]. Last year there were 48 of these deaths. This number is very different when compared with the South Zone of Rio, where during the entire year of 2015, only one person was killed during a supposed confrontation with the police.

With the economic crisis sinking the state of Rio further down every day, along with the absence of public policies, people are left to count on the support of residents who dream of one day living a different reality to that of the current moment. In contrast with this shocking scenario, there are people with the same profile as the victims assassinated by actions of the state who are making a difference in the region. They do whatever it takes to give Complexo do Chapadão a new direction and often occupy roles that the government should assume.

Among them is Jocemir Moura dos Reis. Even though he is over 30, he could easily be characterized with the police victim profile. Jocemir Reis uses incentives in literature as his tool in helping to inform and educate those who live in the favela complex. Philosopher and cultural producer, Jocemir has always loved reading. His father used to bring books home to be restored. At just 11 years old, Plato’s The Republic was the first of many to take him down his current path. Winner of the Extraordinary People Award in the Education category, Jocemir was recognized for creating of the Paulo Freire Community Library in Anchieta. The award recognizes actions that aim to build a better society.

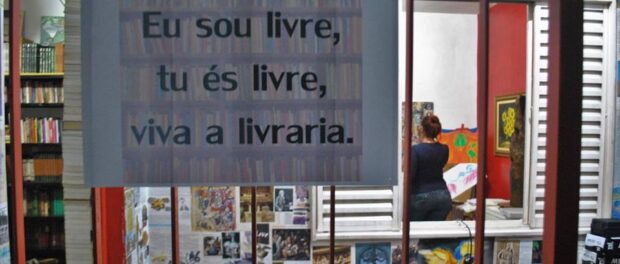

The Paulo Freire Community Library has been operating for 10 years in an area completely ignored by the government. In celebration of the library’s 10 year anniversary, Jocemir created the first FLICC, the Complexo do Chapadão Literary Festival, which took place June 3-5.

Among the beneficiaries is Diogo Oliveira, 25. Having participated in the Lights, Camera, Action project which was a film school that operated for five years in Costa Barros, he personally observed the founding of the community library. Though only a visitor at the time, now he helps with the management of the Paulo Freire Community Library. “In the beginning, I wasn’t part of the team but I did participate in the weekly workshops and debates.”

The desire to provide culture and education for the library’s neighbors is no small thing: “We are moving forward without any public resources, and even though the efforts are for the community, we face many challenges. We have a small team, which makes it more difficult.” However, Diogo never loses hope and he is increasingly seeing that local residents believe in and more actively participate in the projects. “Even with all of the difficulties and problems, we never lose our pleasure in the work. Our audience is growing. We adopted a strategy of always creating events, like literature gatherings, film screenings and exhibitions. The former building relied on a larger assembly of local artists and producers that helped to form a larger audience, but I believe the new building already has a higher number of visitors.”

He admits that during the first stages of the library he was not so involved, and he can’t remember having read more than five books at that time. In his view, studying wasn’t his strong point but the good influences he had were fundamental in helping him not become another statistic on the police criminal records. According to him, his desire to return to his studies was the key to his rediscovery of the library. “I met Jocemir again after a few years and he told me he was forming a study group to help students to get into public universities, so I decided to join. I didn’t have any real intentions; I thought it was impossible for me to get into university until I decided to join. I did well in the program and in 2015 I got into Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) to study visual arts.”

At that moment, Diogo became the first in his family to go to university.

During the FLICC festival, some of the local residents who play a fundamental role in transforming the local culture participated in debates. It was an excellent opportunity to showcase and affirm their activities in the area.

Jorge Wallace, 23, was one of them. Outspoken and a dreamer, “Mais Um” (One More) as he is known, organizes a rhyme battle and a play circle for children. This all takes place in his neighborhood of Pavuna, next to Complexo do Chapadão. Wallace, along with other young people who took part in FLICC, could well also be another statistic on the criminal records. He maybe wouldn’t be alive if it weren’t for social projects. He spoke of appropriating education and culture as tools for personal and community development. “The education methods used in Brazil are very old, which is discouraging, but even so, we need to learn all we can from the remaining good in the school system. Even though some subjects are boring, books are a way out.”

For Jocemir, the main purpose of the event is to showcase the neighborhood as a center of cultural production which has been excessively hidden by mainstream media’s preference to report only on violence. Concerning the local reality, the philosopher affirms: “Our greatest challenge is the fact that people in general don’t see this as a cultural region and therefore don’t adopt this way of life. The impression is that music, arts, poetry, literature are not in the scope of our people, the local residents of our neighborhood.”

According to the study Snapshots of Reading in Brazil by the Pro-Livro Institute, the Brazilian population’s average reading in 2015 was 2.54 entire books or in part. Each reader read 1.06 entire books and 1.47 in part. The Southeast region had the highest average, with 2.98 books. Regarding the Brazilian perception of libraries in the country, the survey showed that libraries are associated mainly with study and research. Though more frequently visited by students, close to 37% of library visitors were not students. Along with other statistics, the survey concluded that the number of residents that know if there’s a library in their neighborhood or city fell from 67% in 2011 to 55% in 2015. Those who were interviewed were asked if they knew of a community library that was maintained by local residents or establishments. Only 15% confirmed their knowledge of one. From this total, only 4% said they use the community library.

During FLICC, it was possible to see these survey results in practical form and how the intention for the festival was successful. Robson Soares, 20, is the son of a public school director and even though he lives on the same street as the Paulo Freire Community Library, this was his first visit. “I didn’t know the library existed, even though I live nearby, but now I hope to make the library my second home. I want to be involved and help whatever way that I can so that the library receives more visitors.” Robson found out about the event from an advertisement on a bus that circulates the favela complex.

Currently, the Paulo Freire Community Library collection has more than 3,500 books and receives around 150 visitors per month. The book titles range from Camões to Julio Ludemir, a Carioca writer who uses favelas as a backdrop for his works.

Ludemir, creator of the Literary Festival of the Periferies (FLUPP), recognizes the importance of the festival. “FLICC is one more action to democratize literature and has the role of creating a dialogue with the whole city. Just because the area is dangerous, people should not avoid it. Besides this, these events reinforce the formation of new readers in the peripheries.”

FLUPP received an award at the London Book Fair International Excellence Awards 2016 in the category of “Literary Festival,” competing with three other festivals, one of which was the the Paraty International Literary Festival (FLIP), which also takes place in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Regarding the visitors of the Paulo Freire Community Library, Jocemir said they are students from the area, mainly from public schools. Teachers, college students and the elderly also utilize the collection. The library has also had its touching moments. Once, an elderly lady visited the library bringing a young boy for reinforcement classes. She was 65, the child’s grandmother, and when she went in to the library, she began to cry. She said she had never seen so many books in one place before and that it was really powerful to be there.

Currently, Complexo do Chapadão is locked in a gang war with another set of favelas, Complexo da Pedreira, dominated by the rival criminal faction. It is not only this war that interrupts the advancement of education and culture there. The police operations, which are necessary to inhibit the constant activities of drug traffickers, also do harm. The schools close their doors at the first sound of gun shots. Parents and their children return to their homes. Since the parents usually have no one to take their children, they lose a day at work. In the last operation, more than 2,000 children were without classes.

Jocemir’s mission, and that of FLICC too, is to be an extension of the school and an alternative. But with all these problems, it is difficult to say if they’ll always be there.

Renan Schuindt, born and raised in Costa Barros, currently works as a producer of journalism at TV Band and coordinates the CineClub Costa Barros. Renan has also done journalistic work for CUFA and Viva Favela among others.