For the original article by Miriane Peregrino in Portuguese published by Jornal O Cidadão click here.

One month ago, residents and supporters of Vila Autódromo chose May 18–International Museum Day–to launch their Evictions Museum. Vila Autódromo is located in Rio de Janeiro’s West Zone, alongside the increasing number of condominiums in the wealthy neighborhood of Barra da Tijuca and where the final preparations for the construction of the Olympic Park are taking place before the Games begin in August. Vila Autódromo was once home to around 580 families but today only 20 families remain, resisting against real estate speculation and the Rio de Janeiro city government’s removals campaign. The Evictions Museum has come about as another tool in this struggle, disrupting the narrative surrounding mega-events in the city.

Conceived as an open-air museum, the Evictions Museum invites visitors to follow a path formed of seven sculptures, fenced off by string. They are:

1. The Light that Doesn’t Go Out, close to the wall of the São José Operário Church where residents hold activities and where they leave pieces of furniture taken from evicted homes.

2. Pillar of Strength, which refers to former Vila Autódromo resident Jane Nascimento, whose house was demolished.

3. I Am the Neighborhood Association, a sculpture that symbolizes the fight to protect the Vila Autódromo Neighborhood Association building from demolition.

4. Sweet Childhood, which represents the children’s park, which was recreated in a participatory way, where residents held various events and activities building community among residents and resistance.

5. Occupation Space / Conceição’s Home, which celebrates the activities that took place in the Vila Autódromo Cultural Occupations, which was held next door to Dona Conceição’s house. Dona Conceição let supporters and visitors to the community use her bathroom and cooked and sold food during the occupations. Paintings of hands feature at the bottom of the sculpture, representing the union between the residents and supporters who worked together to build and rebuild the Occupation Space.

6. The Vila of All Saints is a homage to Heloísa Helena Costa Berto’s house, where she lived and kept a place of worship for [the Afro-Brazilian religion] Candomblé. The house, known as Nanã’s House, was demolished on February 24, 2016.

7. The Many Faces of Penha shows a feminist symbol that represents Maria da Penha, one of Vila Autódromo’s community leaders, who was forcibly removed on the March 8 2016, International Women’s Day.

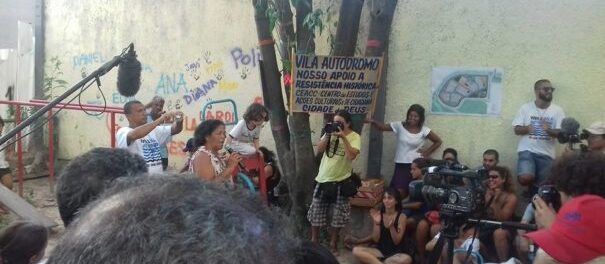

The Eviction Museum’s route was presented by resident Sandra Maria, alongside Diana Bogado from the University of Anhanguera in Niterói and Mário Chagas from the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO). Standing in front of the sculpture commemorating the Neighborhood Association, which was demolished by the City Government, Sandra Maria talked about the loss of the building. “We kept saying that they were demolishing the physical building but that the Neighborhood Association would live on,” she said. “So we wrote the words ‘Neighborhood Association’ on all the houses to make this very clear. The Neighborhood Association is not just a building: it’s much more than that. The Association is a collective organization. As long as there are residents living here, organized, talking to each other, fighting, the Association will stay alive.”

The residents of Vila Autódromo, during these long years of struggle against real estate speculation, created many different types of resistance. Writing the words ‘Neighborhood Association’ on all the houses was one of the most moving forms of resistance, which also served to strengthen the residents as a group. Resident Sandra Regina also highlighted the importance of this collective attitude: “The Neighborhood Association is not a house to be demolished; the Association represents every resident. We are the Association.”

Although the sculpture of the Neighborhood Association is located in the place where the real building once stood, that’s not the case for the majority of the other works that make up the museum. Due to the construction of the Olympic Park, the removals and other transformations in the area, the sculptures that represent Dona Heloísa and Dona Penha’s houses, for example, needed to be placed in other locations within Vila Autódromo.

The house of Heloísa Helena, known by her spiritual name Luizinha de Nanã, stood alone for months inside the Olympic Park before being removed. It is now represented in front of resident Sandra Regina’s house. Dona Heloísa, now an ex-resident of Vila Autódromo, was moved by the homage and talked about how it has been a difficult period for her. Her house was isolated from the rest of the community for months, inside the Olympic Park, and visitors had to request an ID badge to have access to her home. Heloísa and her children couldn’t receive visitors. In the run-up to receiving the eviction notice, her light and water supply were cut.

“I get very emotional when I look at this celebration, which I can take away with me,” she said. “The house was targeted for a long time. We suffered from religious prejudice as well as social prejudice for living here, for Vila Autódromo being here.” Dona Heloísa, who was honored with the Dandara Award by the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly on May 11, talked of how the residents of neighboring Barra da Tijuca never liked having a Candomblé place of worship in the area. “People in Barra da Tijuca are used to seeing black people dressed in white to serve them as nannies or carers, but they don’t want to see them dressed in white for Candomblé ceremonies, playing the abataque drums. The house has gone but I am still fighting for my aims of religious and racial equality. I won’t stop fighting for all of this. And the Evictions Museum helps people be remembered for the struggles they fought.”

Maria da Penha Macena, known as Penha, was also pleased with the museum. In her opinion, finding out about the eviction stories could mean that other removals do not happen in future: “I think Brazilians have a short memory; they forget things quickly. Often we are beaten and then the next day it’s already forgotten. This means that the people that govern us keep on beating us and we keep on forgetting that we were beaten,” she said. “This museum is a way for us to remember the story of Vila Autódromo, as well as the stories of removals under other Rio mayors like Pereira Passos, Lacerda, and so on. If we had remembered more about these evictions maybe Vila Autódromo would not have suffered the same fate. So the Evictions Museum is important because it will ensure that the stories of each and every resident will not be forgotten. The community was trampled on, but it won’t be forgotten. And this kind of thing should happen not only in this community, but in other favelas too. Now there’s also no point having this museum if we don’t help it continue; we have to pass on this knowledge to other people so that the story does not die.”

Resident Nathália Silva spoke about how the idea to create the museum came from one of the community’s supporters and she loved it. “It’s about recovering the history of Vila Autódromo, but at the same time talking about other communities that have been through this process of removal. I am very happy to have taken part in this project. We have been remembering what we once had, the places where we held social gatherings, the residents that came and went in the community and those who resisted, the businesses… to sum up: everything that was important. We called on former residents to celebrate with us: they were invited to participate.”

Thainã de Medeiros, specialist in Museum Studies and resident of Complexo do Alemão, is a supporter of Vila Autódromo and said that memory is a form of resistance and cited the ways memory has been used in this way by residents of Aldeia de Imbuí in Niterói and Horto in the South Zone of Rio as a tool for defending themselves during the process of being threatened with removal.

“In these two places people are resisting through memory, showing that they are not invaders of territory. It is a narrative dispute about who it is that’s being removed,” he said. “Imbuí is showing itself through memory, through documents. They haven’t built a museum but they are using similar memory-building tools to show that they have been living there since the early 1800s. How can they be invaders if they’ve been there for so long? Then you’ve got the Horto Museum too, which is a real museum that was built precisely to show that the residents of Horto have been living there for a long time and that they too are not invaders. The real invaders are the mansions that are being built in the area. So the issue of memory within the dynamics of removals, disputing the narrative over who is the invader and who needs to leave, is very important.”

“The motivation behind the creation of the Evictions Museum is, firstly, to reflect on the context in which removals have historically happened in Rio. It’s a context regarding the construction of the city’s memory, the collective memory of a Rio de Janeiro in which the poorest residents are removed and end up being forgotten,” said Thainã, whose family also went through a process of removal. “The eviction process is always very cruel because it always hits the weakest the hardest.”

Mário Chagas, specialist in Museum Studies and professor at UNIRIO, has also been following the construction of the Evictions Museum. “It’s a museum of resistance and struggle. This museum does not celebrate grief; it celebrates powerful memory, creative memory, memory that looks to the future. It is also a kind of movable museum, which can be relocated to other communities,” he said. “As well as covering current removals, it can look into the history of removals. The museum’s importance is that it documents the strength of Vila Autódromo residents, who are resisting the government’s attempt to destroy a piece of land in the name of mega-investment without taking into account the memory, the lives and the sociability of the people living there.”

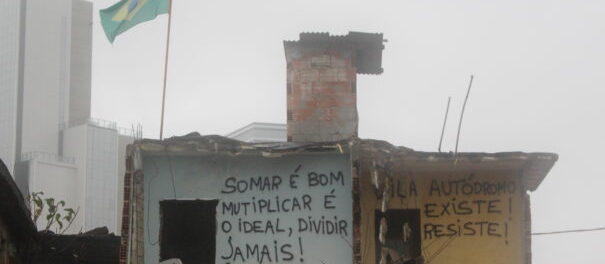

Mário Chagas highlighted that the theme of this year’s International Museum Day is “Museums and Cultural Landscapes” and that this has a direct link with the Evictions Museum: “This landscape of devastated land, this cultural landscape that was destroyed and yet in which new possibilities are being built. Here we are seeing how the authorities are destroying landscapes, interfering in a destructive way. They are building new landscapes here, landscapes that fit their interests but do not respect the landscapes that have been built by those who used to live here.” Mário explains that “the theme of the Evictions Museum’s exhibition is ‘memory cannot be evicted’. The houses can be removed, turn to debris but the memory is there, pulsing, exploding. There’s a kind of poetic and political power here.”

Diana Bogado, architect and professor at the Anhanguera University, presented at the museum alongside resident Sandra Maria. Diana has been working in Vila Autódromo for over a year through a project linked to the university and explained the recreation of the children’s park was one of the project’s first actions. Many community events took place in the park. The second stage of the project was the Evictions Museum, which involved the participation of her students working with residents, conducting interviews and creating the sculptures that make up the museum’s current open-air exhibition.

“As an educational process this was a big success,” said Diana. “Firstly because of the emphasis on participation and also because it was interdisciplinary. We helped in different ways, giving lessons in Vila Autódromo. This resulted in the creation of a map of the community, made from residents’ testimonials. Once we’d mapped the most important buildings mentioned by residents, we chose a few and made the sculptures. As a visitor to and supporter of the community I have found it very interesting to see how we have, through the Evictions Museum, managed to recreate reference points for this area because at some moments Vila Autódromo has totally lost its character. We wouldn’t know which road to take to leave the community, or where the association was located, for example. So with the museum we managed to bring back some of these reference points, which had disappeared due to the removals.”

As well as the sculptures of the Evictions Museum, something else has changed the environment in Vila Autódromo recently: the “container houses.” On May 13 these containers were brought to the community, in order to shelter nine of the 20 families that have chosen to stay there. The Rio city government recently signed an agreement with residents to allow these 20 families to remain living in Vila Autódromo. These containers serve as temporary housing while the City builds permanent houses.

“They wanted us to leave so they could build on this land but we didn’t accept that. We’re not leaving. After breathing in so much dust and facing up to these construction works, why would we want to give in now?” asked Maria da Penha. “Now we want to monitor [the construction of our new] houses because [our original] houses were built by us. These won’t be. They’ll be built by other people who don’t know my story. They have no value to them: they’re just more houses. But our houses are important to us. So we have formed a team of three residents to monitor the construction: they’re going to keep an eye on things and watch what’s going on.”

Sandra Regina is one of Vila Autódromo’s residents who believes in the future of the community and made a comment about the changing distance between the community and the nearest supermarket: “The nearby supermarket is close enough to walk to; it’s not far from here. Where before we used to have to go a long way, to Taquara, to go shopping, now we have a supermarket right next door. We used to have to go and do a month’s shopping at a time. On the way back home we had to get off the bus and walk the last part of the way because the bus didn’t stop anywhere near our houses. Everything was scarce. Access to electricity was precarious. Don’t even get me started on water! The road that used to be here–you can no longer see it, it was where Penha’s house used to be–was made from sand.”

Sandra Regina went on: “It used to be difficult to go shopping. My sister would arrange to go with someone else to carry the shopping, to help her do her shopping for the month all in one go. It was so hard! Now that we’re starting to see progress, we’re being told to leave? No way! It’s now that we have to stay and make the most of it! Because when times were hard it was just us here; now that things are getting better are we going to let this place become for rich people only? No. Rich people have cars, drivers… they have everything. We only have the sweat on our foreheads and our legs. It’s the strength of our will. Now we need to stay here.”

Taking a moment to remember and talk of hopes for the future, resident Luiz Claudio Silva spoke about the years of removals that took place in Vila Autódromo: “What happened was very disloyal. We are a community made up of families in need, fighting against powerful companies: Odebrecht, Carvalho Hosken, Andrade Gutierrez. We were fighting against a conniving government, watching what was going on in our community with its arms crossed. We had to find strength in places where we felt like we had nothing left. We understand why many people gave up: it’s not easy.”

“We used to have 600 families here; now there are 20,” Luiz went on. “Not even 10% of the community remain. The 20 crazy families, that’s what many of the people who left called us. But Jesus Christ was also called crazy because of the way he clung on, the way he talked, and we inherited some of this madness. I turned down large compensation sums. I gave up my house, which was much bigger, in order to accept a house measuring 55 square meters on a piece of land measuring 180 square meters. Many people would say this is crazy, but not me. Because I’m not thinking about the money. I’m fighting to be respected. If there’s a law that says that I have a right to this land, why do I need to leave? To please the authorities, to please the big companies? No way! If there’s a law that says that this is an Area of Special Social Interest for housing, if we have two land titles given to us by two different governors of the state of Rio… at some point this has got to be respected! It’s not possible for us to keep on giving this up.”

Maria da Penha Macena also complained about conformism among Brazilians. “Our country has a big problem. We Brazilians give in very easily. We don’t claim our rights because we think others have more power than us. But we are all equal. Land does not belong to men: we just think it belongs to us when really it belongs to God. Why do I have to sell [my land]? They want to buy my rights. I speak for myself: I didn’t want to sell my rights. Because I consider every negotiation that was done here to be a form of selling our rights, whether we sold them due to pressure, or force, or whether we did it out of ‘free will,’” she said. “I always said that I wouldn’t leave my house. Then when I saw that I was going to lose my house after all, I started saying that I wasn’t going to leave the community instead.”

“I have a lot of faith; I truly believe in God,” Penha continued. “I believe in something you can’t see and I think it was because of this that I have managed to stay living here. I like living my life by sharing with others; everything I own is someone else’s too. I didn’t fight this struggle with anger. I fought out of love. This is a struggle out of love. Love for my history, love for my land, love for my rights. I think that people lose themselves very quickly. They forget to love what they have, they’re always looking to love what they don’t have. I fought out of love for what I have. And what do I have? Nothing. Nothing but my land and the history I created here. And I’m very happy here. I have always said that happiness is not something that can be sold or bought. They tried to buy mine from me, but they didn’t succeed.”

May was an intense month for cultural activities in Rio and beyond: The Museu da Maré, the first museum created by favela residents, celebrated its tenth anniversary under the threat of eviction. On the other side of the city, in the Port Region, the Museum of Tomorrow is being showcased by the government as an official product for Rio’s mega-events. At a national level, the Interim President Michel Temer got rid of and then reinstated the Ministry of Culture. In Argentina, President Macri closed the Bicentennial Museum claiming necessary refurbishment but others have claimed it is a move to “depoliticize” or remove the influence of the left on cultural centers in the country. All this happened during the month of International Museum Day. In a context in which not only memory but also the narrative of history is in dispute, the creation of the Evictions Museum represents a symbolic and fundamentally political act of resistance.