As legend goes, once upon a time there were two blocos (carnival street parties) leaving from opposite ends of Ipanema. In their first year they met in the middle and turned around to return to their point of departure. The same happened in their second year. Then in their third year the two blocos met in the middle… but this time somebody screamed ‘Que merda é essa?!’ (What the ****?!) and the two blocos mixed becoming the now famous ‘Que Merda é Essa?’ bloco of Ipanema.

This story, however, is not typical of the birth or nature of most blocos. This year’s Carnaval sported over 500 blocos, organized by different groups and communities, in all parts of the city and at all hours of day (and night). I spent some time wandering from one to another. I was looking for the truth behind a commonly held myth…

Urban myth holds that carnival is the holiday-equivalent of the beach: it is free and it is for everyone. People intermix ‘democratically,’ without consideration of class or culture. Carnival holds a central place in Brazil’s national culture like no other event, or as Brazilian anthropologist Roberto DaMatta puts it: ‘It was not Brazil that invented Carnaval, but Carnaval that invented Brazil.’

Some hold that carnival is a time when power relations within Brazil are turned on their heads and those most discriminated against in everyday life, the inhabitants of favela communities, become the most powerful in society. A much heard argument supporting the Carnaval as ‘an inversion of hegemonic relations’ is that during carnival favela inhabitants rule the festivities. The spectacular samba parades in the Sambadrome, the postcard picture of carnival, show the incredible organizational and creative talent that exist within favela communities. Carnival is one of few moments when mainstream society and tourists recognize and applaud the hard work of favela inhabitants. It is also said that carnival is the only time when poor and rich, people from the ‘morro’ and ‘asfalto,’ overcome their daily life differences and join together side by side.

However, while joining the different lower key neighborhood blocos–where most locals actually spend carnival–I saw little evidence of ‘equality during carnival.’ As many other bucket list events, the magic of carnival is the product of a collectively imagined and well-managed ideological enchantment that has few roots in reality. The attraction that carnival has on tourists and carioca (Rio locals) alike is based on the portrayal of the pre-Lenten festival as an egalitarian, racially mixed, spontaneous, free-spirited and perhaps somewhat hedonistic event. This image is carefully nurtured and reproduced by a host of people who have a stake in the tourism sector.

I spent my 2012 carnival circling some of the most well-known blocos in Centro, Lapa, Santa Teresa, Ipanema, and Copacabana, as well as several lesser known blocos and parties organized by favela communities. What I found was not the fraternization of cariocas from all segments of society. Neither did I find a completely rigid division of bloco attendance based on social status, ethnicity or place of residence. What I encountered can best be described as a very distinct sense of ‘association’ between a bloco and those participating in it.

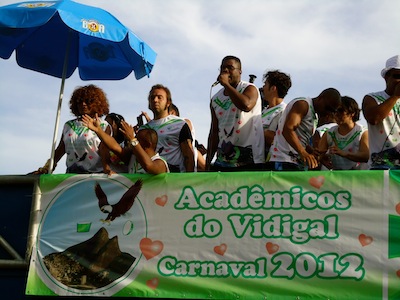

Whilst moving along to Elza Soares singing ‘Madalena,’ at the bloco organized by Vidigal but taking place in neighboring high-end Leblon, several community residents told me that the difference in people at the different blocos is about affinity. One of them explained: “I come here because this is my community, I know these people and I like spending my carnival with them. Also by being here I’m supporting the effort that the community has made to organize this bloco.” But as we moved along the beach, from Posto 12 to Jardim de Alah more people from neighboring apartments joined the bloco. An elderly man in a white polo, white shorts and brown moccasins told me that he heard Elza Soares singing and that her songs brought him to the street: “Usually I don’t come down for these kinds of blocos but I could not let this opportunity pass up.” When the Vidigal bloco ended I continued to Ipanema and joined the ‘Que Merda é Essa?” bloco.

The transition from one bloco to the other was noticeable not only due to a change in music but also the changing demographics of participants: they were younger and whiter. Especially visible was a sudden rise in ‘Ray-Ban’ glasses and people filming with their iPhones. I walked into a group of PUC (Rio’s Catholic University) students, both international and Brazilian. When I asked how they had chosen this bloco they answered that they were on the beach at Posto 9, then heard and joined it because they knew most of their fellow students were there. “Most of us live around here or in Gávea close to the university,” said Jay, an American exchange student, “So it’s easy and besides I know that my classmates are here as well. For me Carnaval is also about the people I spend it with.” When I asked if they would join a bloco organized by a favela the reactions were mixed, the Brazilian students more hesitant than international ones. I asked one of the Brazilians why. She said “it has nothing to do with prejudice or anything. It’s just, I don’t know, they are very tight-knit communities, I would feel out of place.”

The people I spoke with left me with the impression that even during carnival people retain a very strong sense of beloning to a certain place and group in society; that each of these groups has their own ‘rules of conduct,’ which especially for the higher classes involve strict instruction on who (not) to associate with.

The most mixed crowds and the least talk of feeling in or out of place I found in blocos like Boitatá, in Centro, Rio’s historic downtown. This can be explained at least in part because Centro is just that–the center of the city–and few people live there so those coming to the blocos come from all over for the particular atmosphere and music offered.

Carnival, especially in Rio de Janeiro, is seen as the event representing what is most alluring about Brazilian culture and life. Yet in reality carnival also represents the negative aspects of Brazilian society. It shows how Brazil is still segregated with little communication or fraternization between different segments of society. And carnival as a festivity that would somehow magically bring people together of all walks of life is just that: a myth.

Sources

DaMatta, Roberto

1987 The quest for citizenship in a relational universe in: State and society. In Brazil Continuity and Change. John D. Wirth, Edson de Oliveira Nunes and Thomas E. Bogenschild, eds. Boulder and London: Westview Press.

Sheriff, Robin E.

1999 The Theft of Carnaval: National Spectacle and Racial Politics in Rio de Janeiro. Cultural Anthropology, 14(1): 3-28.