On Saturday July 16 activists and residents of Complexo do Alemão in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone participated in a peaceful demonstration to denounce violence—which has escalated in recent months in anticipation of the Olympics—and to draw visibility to the intense police presence and absence of adequate public policies.

The demonstration was organized by local media collective Coletivo Papo Reto and community-based newspaper Jornal Voz das Comunidades, with support from other civil society groups and residents of Complexo do Alemão.

The event, which garnered significant local and international media attention, began at the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) base on Itaóca Avenue. Holding a torch marked with red handprints to represent the blood of victims of violence, Raull Santiago of Papo Reto addressed the group:

This is an action to call attention to the condition of violence in which the majority of favelas are living, which has intensified with the approach of the mega-events in Rio de Janeiro. In 2007, when the Pan American Games took place, Complexo do Alemão received a mega [police] operation in which many people were killed—this was the principal legacy of the Pan in Complexo do Alemão. During the process of the World Cup, military interventions in the favela intensified, as well as the increasing violation of rights in Complexo do Alemão. Once again, our ‘participation’ in the mega-events meant receiving a large contingent [of forces] to militarize space. And now, with the Olympics, this is repeating.

Raull pointed to the disjuncture between the rhetoric of unity associated with the Olympics and the reality of pre-Olympic Rio for residents of the city’s favelas, stating:

This torch is a symbol, but it’s not a criticism of the idea behind the Olympics and what it signifies. For us, it signifies the way by which the City of Rio de Janeiro, the State and Brazil are going about the event in our city. Because the ideology of uniting people that the Games propose is brilliant. But the reality of our city is the opposite—there is a lot of violence, painful situations and various problems within the favelas.

Four years after the implementation of the first UPPs in Complexo do Alemão, gun violence remains nearly a daily occurrence. As of July 17, Voz das Comunidades has counted 35 injuries and deaths (of both civilians and police) resulting from shootings in the complex’s favelas this year—a figure which represents one person shot every five days. A shootout beginning at 7am on the morning of the demonstration prevented some residents from participating. Accordingly, the cable car stopped functioning due to security concerns.

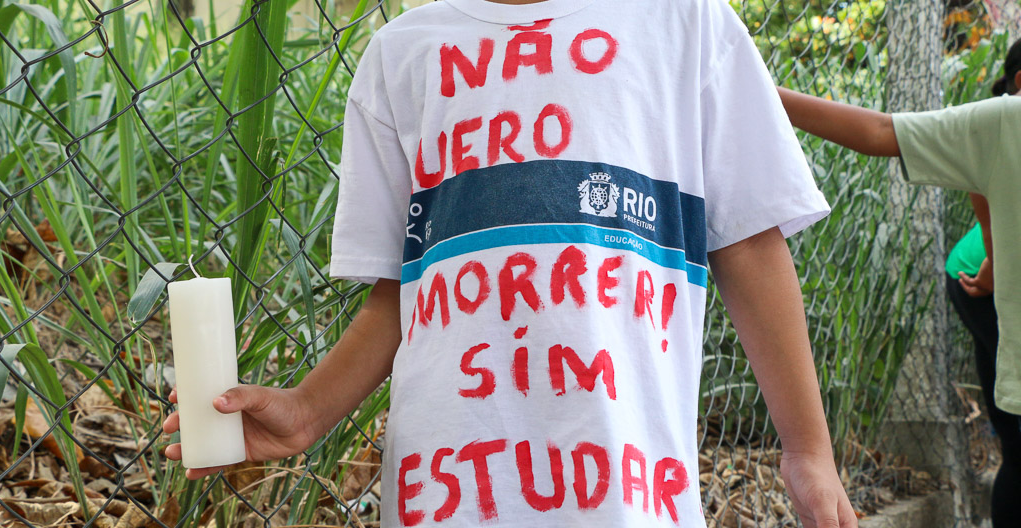

Highlighting this discrepancy between the hyper-presence of the State in the form of policing and the absence of the State in other areas of public policy such as education, housing and social services, Raull described:

The only public policy—and the principal participation of favela residents in the Olympic Games in planning the city in recent years—has been engagement with us from the viewpoint of the police’s rifle. This modus operandi follows the same logic of the so-called ‘war on drugs,’ in which residents die, police die, and nothing changes. We continue to die… The losses are losses of the poor. They’re losses of youth, who in this society, in the way of drug traffic, get weapons and begin to kill and die. They’re police who, abandoned by the State, unpaid, in a situation of violence, are thrown into the favela to kill and die… And principally, us. As targets of both rifles, we receive what they call ‘stray bullets’ every day.

Thainã de Medeiros, also a member of Coletivo Papo Reto, read the names of recent shooting victims in Complexo do Alemão—civilians and police alike. Thainã called for a moment of silence in their memory after the names were placed in a cardboard casket.

Demonstrators then carried the torch and casket as they marched down Itararé Road, occupying the street. The group briefly paused in front of Complexo do Alemão’s urgent care clinic (UPA), often the first destination for shooting victims in the area.

The march concluded at the entrance of Grota on Joaquim de Queiroz Road, where the group gathered next to the street market. Lana de Souza, also of Coletivo Papo Reto, read aloud the names of a handful of living individuals, emphasizing the urgency of current circumstances as a reminder that anyone in attendance could be the next victim of gun violence: “We need to do something, or the next name could be yours.” Next, Raull recited lyrics of a funk poem he authored, calling upon residents to say “Enough!” to the daily violence experienced in this “war for peace.” The floor then opened up for residents to speak up and share experiences.

In light of the escalating violence, it is essential to recognize forms of community-based mobilization and resistance. As Thainã stated: “The favelas are very much alive… despite attempts to silence them and contain these social groups.” In a similar vein, Voz das Comunidades journalist Daiene Mendes recounted in her recent piece featured in the Guardian’s ‘View from the Favelas’ series: “We are ‘traffickers’ of culture and information… Our weapon is our narrative, and our struggle is for the right to live in Alemão and the chance to live together without daily shootings, without the terror of the police, without fear of drug traffickers.” The work of Papo Reto and Voz da Comunidade attests to the power of media activism as one such form of resistance—bringing visibility to the reality the Olympic City as experienced by residents of Alemão.