Documentary film The Fighter tells the story of Vila Autódromo, the favela that borders the Olympic Park in Barra da Tijuca in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, through the eyes of 12-year-old Naomy.

The Fighter was funded by the NGO Terre des Hommes‘ campaign Children Win, which specifically aims to examine the effects of mega-events on children living in host cities. The film’s narrative arc begins back in 2014. Naomy reveals that her first introduction to the Olympics was in the context of having to leave her community where 900 families originally lived.

A series of idyllic images introduce life in Vila Autódromo prior to Olympic construction: sun reflecting on the water and silhouettes in front of Barra da Tijuca’s modern urban skyline while paddling across the lagoon in small boats. Naomy talks about catching and eating alligators with her father, a fisherman in Vila Autódromo, as an alligator glides through reflections of clouds. But the film’s thematic focus—the trauma and powerlessness felt by children impacted by forced removals prior to the 2016 Olympics—is quickly introduced, and suddenly Naomy is shown standing amid the rubble of her favela and a few remaining trees. The sense of personal inability to control events is reinforced throughout the film, with footage of residents looking on as construction workers wield sledgehammers and diggers effortlessly tear down walls.

Vila Autódromo’s destruction, both as a physical space and a community, is reiterated throughout The Fighter. Naomy remarks how Olympic construction has polluted the lagoon, destroying the fishing trade which was once the community’s main economic lifeline. The camera watches as she walks past a pink dawn on her way to school, with construction already underway. As the film’s trajectory travels towards the present day, the number of residents remaining and the hope among those who stay dwindles. Naomy’s friends and her mother’s family are among the many residents who lose hope of holding on to their properties and move away.

The lack of safe space for children is a theme emphasized throughout the film, with footage of children playing next to moving diggers and on second stories of half-destroyed houses in what remains of Vila Autódromo. But the alternative provided by the City, the Minha Casa Minha Vida (MCMV) public housing project Parque Carioca where Naomy’s mother moved to, is not presented as a more child-friendly space: small apartments instead of houses, with limited indoor space and no recreational space for children.

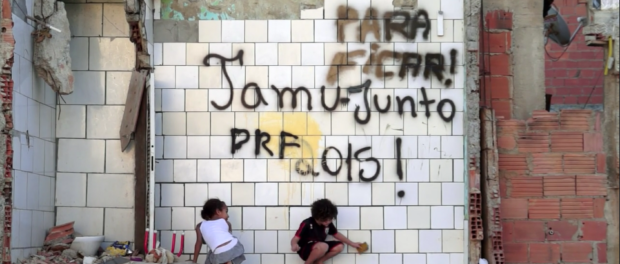

The Fighter explores how the City undermined residents’ autonomy, demolishing homes and using police brutality to intimidate citizens and injure peaceful protesters. One such incident results in activist Maria da Penha’s bloodied nose and black eyes, which can be seen in one interview in The Fighter. Naomy’s father Altair is forced to build a new home after his original house was demolished–although this house, too, was destroyed with the help of Shock Troops after The Fighter’s filming finished. But Naomy possesses even less power than adult residents. Unable to attend protests where police brutality is a possibility, Naomy’s uncertainty is contained in writing and the reflections she shares with the camera. She thinks constantly about what will happen to her next, where she will live, what will happen to her friends and the people who used to live in her community, and where Rio found the billions of reais needed to host the Games.

The Fighter’s examination of how mega-events such as the Olympics and the World Cup can violate housing rights focuses clearly on how severely children are affected by these changes and the trauma that stems from the instability created. While the film ends on a hopeful note—Naomy, walking past a setting sun, resolves to continue the fight for recognition of her rights—The Fighter’s compelling account is just one of many similar narratives across Rio de Janeiro, where government-enforced displacement has sadly become commonplace.

The 20 remaining families in Vila Autódromo have since reached an agreement with Rio’s government to remain—in newly constructed homes—and were given keys to their new houses this Friday July 29. Naomy and her father were not among the families able to remain living in the original location of Vila Autódromo. They are now renting as they build a new home and life for themselves thirty minutes away.