Vila Autódromo has fought against Olympic evictions for years. They waged a strong, passionate campaign to assert their right to remain on their land, where the community has stood for over 40 years. Creative resistance tactics were used, ranging from an award-winning upgrading plan that showed how the city could easily and less expensively integrate them into its plans, to a viral video campaign based on the hashtag #UrbanizaJá (upgrades now), to daily updates of graffiti on the walls which left visitors in no doubt what residents thought at any given time about the city government’s actions there. Slowly and through ever escalating tension, even violence, however, the community of 600 families was whittled down to just 20 remaining families through a combination of intimidation and increasing compensation. In April, thanks to the community’s unity and determination, constant support from Rio’s Public Defenders and activists across the city and the world, and an ongoing international media spotlight, the remaining residents won a landmark deal to stay–the first collectively signed favela housing agreement in Rio’s history.

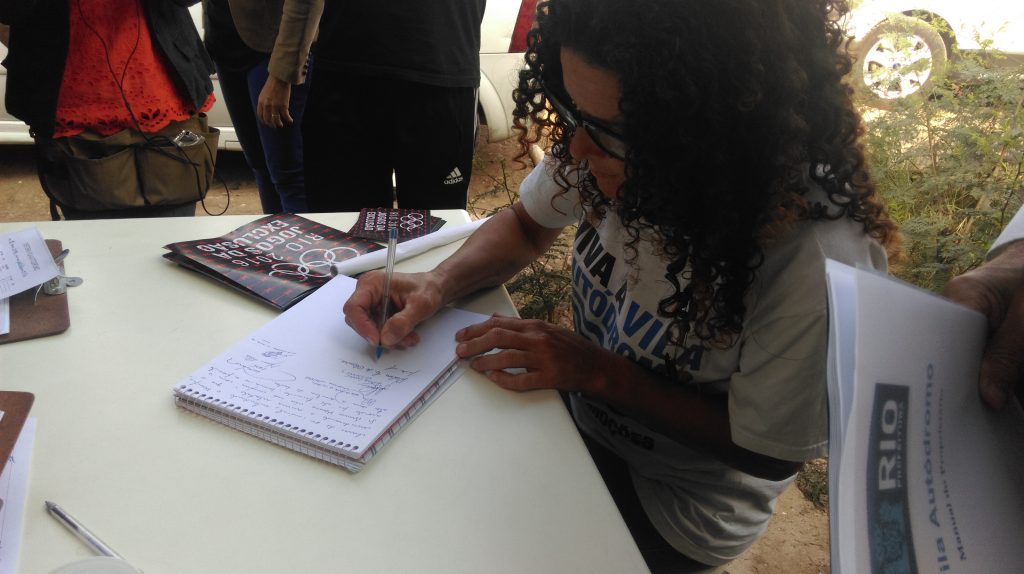

According to that agreement, the houses were due to be delivered on July 22. Slightly delayed, on Tuesday July 26, residents prepared to receive their keys from the city. Instead, however, they found that the works were not yet completed. The power was not connected to the buildings, there were no streetlights on the road, and the road to the community church–the only building that will remain from the original community–was not complete. Unable to trust that the city would finish these projects if they took the keys, residents refused delivery of the “half-built houses.” Public defenders drew up an agreement, signed by city officials and residents, stating that the city would finish these projects and deliver the houses before the Olympics, with residents hopeful of receiving their homes by the end of that week.

On Friday July 29, residents prepared again to receive their keys. With representatives of the city and public defenders, residents inspected the houses one by one, ensuring they were properly finished. After inspecting her home, Antônia Henriques, the mother of community activist Maria da Penha said she loved it, beaming a wide smile across her face. But for many, this joy was tempered by happy memories of their old homes. As Luiz Claudio Silva said after inspecting his new home, a fraction of the size of his old one: “It is not the dream, but it is a good house.”

The thorough inspection of the houses revealed some small issues that still needed to be resolved by the city, such as windows not closing quite right. These issues, it was decided, were not big enough to stop the houses from being delivered. The public defenders and city officials then thrashed out a legal agreement for the delivery of the homes, giving the city a deadline of ten days to fix the issues. Public defenders were also careful to include obligations for the city to provide further upgrades to the community. During an interview with NBC, the city official responsible for delivery of the houses gave his assurance that the area around the new houses of Vila Autódromo will always be public land, not used for profit, contrary to residents’ fears that it will be used by unscrupulous property developers after the Games.

Once the legal agreement was written, 82-year-old Dona Dalva became the first resident of Vila Autódromo to receive her keys and the title to her new home. The other 19 families followed, signing the agreement and receiving their keys to the applause of a small crowd. Sandra Regina, on receiving her keys, lifted her arms to the sky and shouted “Victory!” Residents will move in over the weekend, and the final homes remaining in Vila Autódromo will be torn down.

The now well-known couple, Luiz Claudio Silva and Maria da Penha Macena, are looking forward to writing “a new page in their story” in their new home. Maria da Penha feels finally that “the community’s rights have been respected, having fought for so long for this to happen.” But she won’t be stopping fighting. For her, “the fight for housing rights goes on, with many other communities in the city still suffering.”

“This victory,” she says, “isn’t mine, isn’t Luiz’s, or even Vila Autódromo’s. It is for all the city of Rio de Janeiro.” It is worth remembering that for each family who gained a new house in Vila Autódromo, over 1,000 other families have been forcibly evicted from their homes since the city won the right to host the Olympic Games in 2009.

Vila Autódromo’s victory comes against all the odds. It serves as an inspiration to other communities facing evictions, not just in Rio de Janeiro but all over the world. This victory also serves to strengthen protest against the Olympics’ severe impacts on host cities. Activists are often told they won’t stop the Olympics, and that there’s no point protesting the impact of the Games. But this victory shows that when people are determined and organized, even in the face of the largest real estate interests in the nation under the guise of an Olympic-imposed state of exception, anything is possible.