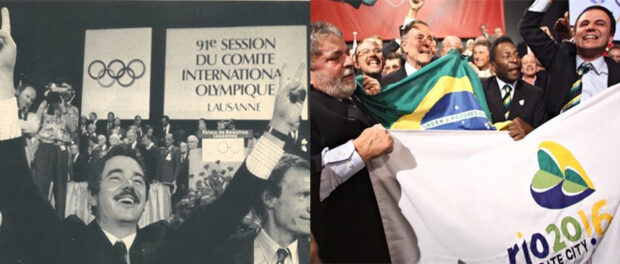

In September 2015 the mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Eduardo Paes, wrote an opinion piece in Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo proudly proclaiming that the Rio Olympics would leave the most important legacy in a city since the Barcelona 1992 Games. Titled “The Inclusion Games,” the mayor’s article echoed the words of International Olympic Committee president Thomas Bach, promising that the changes in the Olympic City would improve the lives of all Cariocas, particularly the poorest.

The article enraged social activists and residents who have felt and fought against the perverse effects of the city’s Olympic preparations. Incidentally, the opinion piece gave the Popular Committee on the World Cup and the Olympics the appropriate title for their extensive dossier on the human rights violations related to the mega-events: The Exclusion Games. The slogan has become a rallying cry for many movements culminating with today’s protest, to take place near to and slightly before the 2016 Olympics Opening Ceremony, titled Action “Rio 2016 — The Exclusion Games”.

There are clear problems with comparing Barcelona, a city of 1.6 million inhabitants in Europe, with Rio, a city of 6.4 million inhabitants that is still struggling to reconcile the fragmented society inherited from times of slavery. Although Barcelona did have concentrations of barracks that were “eradicated” following a policy that criminalized and displaced local Roma populations, it does not match the starkness of Rio’s dual city, divided between the vast, chronically underserved, informal settlements and a richer formal city. Furthermore, Barcelona’s undeniable boom following the 1992 Olympics was boosted by various factors, including Spain’s entry into the European Union, while Rio’s Olympics will occur in the context of a national economic crisis, political instability and the recently announced “state of public calamity” in the Rio de Janeiro State.

The mayor’s pretentious comparison with Barcelona can only be regarded as a desperate attempt to distract observers from the mass forced evictions from favelas, environmental degradation, and persistent police brutality and systematic killing of young black men associated with these times.

Nevertheless, the urban development model Rio has followed for the last two decades has been largely inspired by the so-called “Barcelona Model.” Catalan consultants played an influential role in the creation of Rio’s municipal strategic plan in the years following the “success” of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Through meetings between Catalan consultants and Carioca authorities, key ideas derived from the experience of Barcelona were introduced to Rio. This included a specific planning model that considers cities as strategic economic nodes located in a competitive environment, and which considers a main function of local governments to be controlling and selling the image of the city in the global marketplace to attract investment.

After two decades, it is still unclear to what extent Rio has followed the strategic recommendations that the exporters of the “Barcelona Model” intended to share, but the city’s huge marketing budget suggests Rio is trying to attract investment through brand management. However, Jordi Borja, the creator of the Barcelona Model and consultant to Rio authorities, has since openly distanced himself from the speculative and clearly exclusionary planning strategy that Rio has followed during the past seven years.

Barcelona 1992: a flawed model?

Does Barcelona even offer a model worth aspiring to?

Barcelona began to gain international renown for its planning achievements at the beginning of the 1980s, when the first democratically elected municipal government after the long Franco dictatorship took office. These were times of hope among local citizens. A widespread atmosphere of social-democratic triumphalism created a consensus on the type of planning interventions that the city urgently needed to improve socioeconomic and material conditions for the population.

Socially-minded planning solutions were particularly urgent in light of the global economic crisis in the 1970s, which had a strong impact on a degraded, deindustrializing Barcelona that was sliding further into deepening social segregation. Conversations with Catalans over 40 years old always reveal how major and rapid the city’s transformation was in only a decade. In the early 1980s, local authorities used urban planning as the main strategic tool to counter the effects of the crisis, generating and promoting economic activity based on services and the cultural sector, and building and improving public spaces and facilities both in central and peripheral depressed neighborhoods.

This development model based on socially-oriented small-scale interventions changed after Barcelona won its Olympic bid in the second half of the 1980s, when growing financial resources permitted large-scale interventions and the improvement of basic infrastructures such as mobility networks and sewage. The City’s planning efforts rapidly shifted towards generating economic growth, cosmetic changes, preparing sports and accommodation facilities, the development of iconic architecture and the increasing inclusion of the private sector to efficiently develop specific projects in partnership with the public authorities. In short, the priority shifted from helping the population to preparing the Olympic party.

In Barcelona, the opening of the city towards the sea and the construction of an urban beach was a popular Olympic project that remains a positive legacy for the population. But other large urban redevelopment projects, particularly those in the city center and along the waterfront districts, were highly speculative and destructive in many ways. Large-scale urban transformations like the construction of the Olympic Village and of the 22@ district transformed working-class and industrial quarters into a tourist and entertainment hub and a financial district, respectively.

The building of these districts provoked the destruction of the social fabric and bonds that existed in the areas before the interventions, the displacement of small and local businesses due to the pressures of economic competitiveness, and even the destruction of architectural heritage. Moreover, the creation of gated and private condominiums particularly in the Olympic Village represented a privatization of space. Projects like the Olympic Village resonated with previous plans powerful landlords had called for during the dictatorship period.

Transformed into a growth machine that championed tourism and real estate speculation, the drift that the “Barcelona Model” took in the years before the Olympic Games and afterwards made it unrecognizable even for some of its creators. It was only a matter of time before the unsustainability of the model became evident. Since the start of the economic crisis and recession in 2008, a “state of social emergency” has compounded persisting problems associated with mass tourism and gentrification. Tens of thousands of families who could not afford mortgage payments have been forcefully evicted from their homes; levels of unemployment skyrocketed, especially among the youth; struggles to afford electricity and water bills became a widespread reality; and the real risks of social exclusion multiplied.

Barcelona did not, and still does not, have a thorough social housing policy that serves both the wealthier and lower-income parts of the city; no legislation was ever made to protect residents from the effects of rampant gentrification in central neighborhoods. These factors combined to help Ada Colau, an anti-eviction activist leading the new leftist coalition “Barcelona en Comú” win the municipal election a year ago, signaling a public desire to move away from the city’s obsolete and socially harmful development model.

The real model: learning from the bottom up

Barcelona is no model and has no magic Olympic formula that can be simply exported and implemented anywhere in the world. If any parallels can be drawn between Rio and Barcelona, they are to be found in the mobilization of residents to defend their collective interests and the right to the city against the Olympic city projects and the prolonged marketization of the city as a brand. Cities, local governments and, most importantly, residents should not become seduced by the strategic marketing of official discourses that claim to reproduce exemplary models.

In Barcelona the city’s transformations since the early 1990s have provoked strong opposition from neighborhood associations and civil organizations. Organized residents fought both against the destruction of historical heritage (such as the industrial patrimony in the district of Poble Nou) and for the inclusion, in the city development plans, of facilities in more peripheral neighborhoods.

Andrés Naya and Albert Recio, resident-activists from Barcelona, reflected on the lessons they wanted to share with activists in other Olympic cities: “They should not have to wait to see if the Games radically improve the situation [before mobilizing], and they should promote well-organized campaigns around concrete objectives. Also, they should not expect many allies. We all know that mega-sports events alienate many consciences.”

These conclusions and struggles are comparable to those of Rio’s residents and activists who struggle against state violence and the evictions of entire communities, and who fight for education, decent housing, and the improvement of living conditions in lower-income neighborhoods and favelas.

The Federal Fluminense University’s human geography scholar Jorge Luiz Barbosa explains that “Barcelona would never have reached the international prestige it has today if it had not been for the social and urban conquests promoted by struggles of the residents’ movements.” Such lessons should be adopted in the forthcoming Habitat III United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development: no copy and paste urban development model based on market-driven investments and municipal marketing will ever generate an egalitarian city. The most valuable lessons are to be learned from the bottom-up.