The world watched on Friday as the Rio 2016 Olympics‘ opening ceremony took place in Maracanã stadium. Incredible fireworks, colorful costumes and smooth Bossa Nova filled the air. It was, in many people’s eyes, a spectacular ceremony. President of the Rio 2016 Organizing Committee Carlos Nuzman, a former Olympian, declared that “the Olympic dream is now a wonderful reality” and the “transformation [was] promised and delivered.”

However, Brazil’s history is complicated and painful, and many from the historically disenfranchised groups represented whimsically on stage felt the ceremony whitewashed reality “for the English to see” as is typical here and was described last week in a New Republic piece entitled “Brazil’s Long History of Faking Progress.” The opening ceremony, directed by City of God director Fernando Meirelles, paid homage to some of those themes, namely mass enslavement of Afro-Brazilians and violence towards indigenous peoples, in recognition that they’re not “pretty” parts of Brazil history like beautiful landscapes and diverse culture. Time Magazine called this depiction “compelling”.

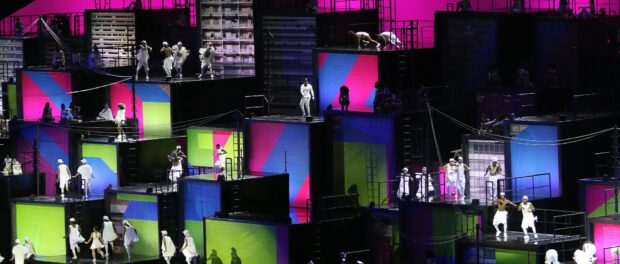

In the case of Rio’s favelas, the overtly happy tone was seen by many as painful to watch, masking over the pain and deep-rooted suffering such communities have experienced due to widespread stigmatization and public sector neglect for nearly 120 years. One particularly poignant and present-day example was the contrast between the colorful backdrop of stacked boxes, which was an unmistakable nod to Rio’s favelas, and the huge number of forced evictions (77,000) around the city due to the Olympics’ arrival. What is the message here? Something along the lines of “favelas are okay as long as we can portray them artistically and appropriate their aesthetics and culture, but we don’t value them enough to upgrade them and protect their culture in real life.” This is certainly what we have seen in the disastrous implementation of potentially beneficial public policies like Morar Carioca and the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) in recent years.

The attempt to reconcile and acknowledge the systemic issues that exist in Brazil extended throughout the ceremony. Before the show even debuted, one skit was cut because its message was deemed unacceptable. As reported by Folha de São Paulo, supermodel Gisele Bundchen was originally supposed to be “robbed” by a young black boy while walking out to “The Girl From Ipanema.” Meant to acknowledge the difficulties Rio and Brazil still face today, the mere consideration of this skit is a testament to how disconnected the ceremony’s producers appear to be with regard to their own assumptions, as well as the potential worldwide impact that such a public display of prejudice can have.

Residents from Rio’s favelas and other commentators took to social media during and after the ceremony to express their anger at the portrayal of their city and country.

“One of those boys dancing next to Regina Casé could have been young [dancer] DG that was assassinated by the Rio de Janeiro Military Police. To think that everything is a party and only talk about the beautiful stories of overcoming in the favela is a huge hypocrisy. Yesterday in the Olympic City here in City of God a car was gunned down with a machine gun. Sorry, but I am not in the ‘Olympic Spirit,’” wrote Wagner Novais, a filmmaker and resident of City of God.

Other residents criticized the ceremony for only showing the parts of Brazilian history that would be agreeable for the foreigners to see.

“It has the city of Parintins and the indigenous in an Amazon without conflicts. It has black people only as slaves, but where is Black culture? Where is Candomblé? Where are the poor? The funk music and pagode are plasticized. It has ecology for the foreigners to see… Strangely beautiful, absolutely competent, but without soul, without conflict and without truth! It is a lesson in the construction of brand advertising,” said Ivana Bentes, a communications researcher and professor at the Rio de Janeiro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Léo Custodio, a researcher from Magé in the Baixada Fluminense, offered suggestions as to how the opening ceremony could have been a more realistic depiction of Brazilian history:

- When the Portuguese ships arrived, there could have been indigenous people on the ground symbolizing the genocide of the indigenous people.

- There could have been actors with whips hitting the slaves. The trail left by the slaves was red, not white.

- A dancer falling from the building at the end of the construction of the city to symbolize the indifference to poor workers.

- The dance of the favela [could have ended] with the body of one of the dancers fallen on the floor between one actor representing the drug traffic and the another representing the Military Police, both of them with a rifle. The rifle of the Military Police would be white to represent (the) pacification (program).

- Before the entry of the athletes, I suggest a scene where the tractors destroy the houses of the poor to open a path for the delegations to pass through.

- At the ‘Pyre of the People,’ instead of fireworks at the Candelária, the church could have been lit up red to symbolize all of the boys–like the one that lit up the pyre–that the city buried and killed in the process of preparation for the mega-events.

The ceremony included a battle scene where groups in different colored costumes vied for power that was meant to represent the many different struggles in Brazil like race, colonization, imperialism and socioeconomic status. What seemed to solve it all was a peace broker who intervened to unify the groups through dance. For those watching the opening ceremony from the favelas, this simple solution and oversimplified illusion of unity undercut the problems and left many frustrated by the vanilla flavor of the opening that missed out on the realities that have existed for centuries, unchanged, now exacerbated and flavored by the Olympics.

“What a beautiful ceremony and the ‘Olympic sun’ as well. Everything was very beautiful, truthfully. But not worth the removal of a single home,” wrote Thiago Diniz, photographer and cultural producer with North Zone collectives Norte Comum and Imagens do Povo.