On Saturday, August 27, journalists, students and members of community media organizations from across Rio de Janeiro gathered at the Museu da Maré to debate the role of Rio’s community media in the first Community Communication Congress.

The Congress was hosted by the journalists of O Cidadão, a newspaper based in Complexo da Maré in the North Zone. Around 45 audience members listened to a discussion on topics including the definition of community communication, community versus mass media, the importance of supporting local creators and artists, production practices and challenges and whether objectivity is possible or even desirable for community reporters.

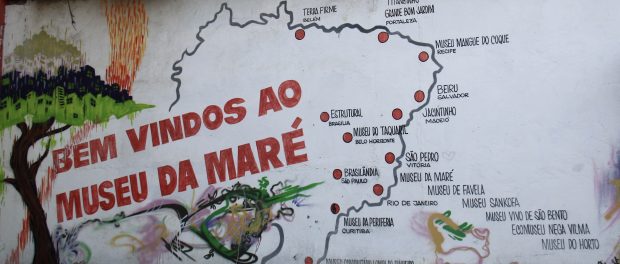

The event received support from the city’s Secretary of Culture, the Maré Center of Solidarity Studies and Actions (CEASM), the Museu da Maré and the Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação (NPC), an NGO that supports communications initiatives within social movements and unions.

According to organizers, the Congress was inspired by questions that emerged among members of community media in response to the past decade of mega-events in Rio, culminating with the Olympics, and the corresponding repression of favela residents and censorship of community media outlets.

The broad themes up for discussion included how to strengthen favela identity within the city, combating criminalization of favela media and the population, bringing more reliable information to a broader audience, promoting and supporting local artists through community communication and leveraging community media to express and reflect the interests of favela residents in a post-Olympics context and municipal election year.

Community media and mega-events

Participants tackled these complex questions in a series of three panels. The first, on community media and mega-events, featured Maré resident and O Cidadão journalist Gizele Martins.

Martins discussed some of the challenges facing community media outlets, including the power of a mainstream media and society that marginalize and stigmatize favela residents, contributing to stereotypes that favela residents are “criminal, violent, marginal.” She also criticized the fact that ownership of Brazilian mainstream media is dominated by a few wealthy families.

Martins presented community media as a vital contrast to the racist, discriminatory ideas and images spread by commercial media outlets.

“We’re talking about our identity,” she said. “It’s very important that we are a source of information, both for each other and for favela residents. We need to organize ourselves, to create alternatives, to continue creating a network of community media in the favelas. Community communication is a form of mobilization, primarily of thought.”

Martins also pointed to the important role of independent media in bringing attention to topics and stories that rarely appear in mainstream media through community-run channels like the Maré Vive Facebook page.

“If we didn’t have Maré Vive, we wouldn’t know about all the people killed in Maré during the mega-events,” she said. “Who is going to talk about the genocide of the black population, if not us?”

Challenges for community media

The second panel, on challenges facing community media, included Silvia da Costa, columnist for the Jornal Abaixo Assinado de Jacarepaguá; Wladimir Aguiar, a radio journalist with Rádio Maré; and two representatives from independent street cinema collective TV Tagarela, in Rocinha in the South Zone.

Da Costa highlighted the importance of making community media democratic and accessible to both its audience and contributors. The Jornal Abaixo, based in Jacarepaguá in Rio’s West Zone, accepts contributions from anyone who wants to write, regardless of formal training or previous journalism experience.

“If you have opinions, if you have ideas, you can write,” she said. “We’re producing another kind of media. Community media can reflect what people think.”

The commitment to publishing a wide range of contributions can lead to internal debate, she said, since staff may not always agree with the content being printed–or even with each other.

“It has a good side and a bad side,” she said, but emphasized that maintaining the right to freedom of expression is more important than agreeing with everything that appears in print.

Aguiar discussed the role of community media in serving the needs of its audience and empowering them to participate more in civic life.

“We can lead the community to empower itself,” he said. “Favela residents live what’s happening around them, and we can amplify that conversation.”

He also provided a historical overview of the development of community radio in Maré and other favelas, reflecting on the progress since the days of the military dictatorship, when such forms of communication were banned.

Camila Perez, from TV Tagerela, explained the history of the street cinema collective and its recent achievements, including hosting the first Favela Film Festival in June 2015. She also highlighted some of the challenges facing the collective, including obtaining permits, working around the disruptive and intimidating presence of police, and widespread discrimination against favela residents.

“I can’t believe that this [discrimination] still happens today,” she said. “Everything is more difficult when you’re from a favela, but we keep fighting.”

Moderator Carolina Vaz, from O Cidadão, described some of the newspaper’s challenges, including the lack of an established workspace. The journalists meet regularly in Maré to coordinate and discuss their work, but their meeting space has no Internet access, so they do most of their writing independently.

Da Costa concluded with an impassioned take on the political role of community media and the illusion of objectivity.

“There’s no such thing as impartial media,” she said. “Any form of communication–oral, audio, visual, TV–is partial. When you decide to be someone who shapes information, you have to choose a perspective. Choosing has a consequence of picking a side, a partiality.”

“At the Jornal Abaixo, we have an editorial line,” she continued, explaining that the publication’s position on issues reflects the views of residents. “For example, we don’t understand the UPP (Pacifying Police Units) as providing security, but rather as repression,” and articles reflect that perspective.

She emphasized a link between community media and activism, echoing other speakers who acknowledged the inherently political nature of alternative media.

“Every one of us, within our vehicles of communication, has to take a position, and that is a political position.”

Community media and corporate media

The third panel examined the roles of community and mainstream media, and featured Thainã de Medeiros, a member of Coletivo Papo Reto in Complexo do Alemão, and Tatiana Lima, a journalist with the communication NGO NPC.

De Medeiros traced the history of Papo Reto, which was created in 2014 as a means to share information, support and mobilize community members in Alemão.

“Papo Reto is an exchange of experiences,” he said. “We engage in communication to mobilize people. Not just to go out into the streets to protest, but to create actions in the communities. Sitting down to talk is very different from going out and doing something beyond the conversation.”

He described Papo Reto’s efforts to counter the narrative promoted by mainstream media.

“We do communication to guarantee our rights,” he said. “We take an article that appears in corporate media, and we do our version.”

In discussing mainstream media’s treatment of favelas, he also critiqued the broader appropriation of favela culture by other parts of society, from funk-themed parties with expensive cover charges and mostly white attendees, to wealthy Brazilians wearing t-shirts featuring the word “Favela.”

Lima seconded the importance of using community media to fight appropriation of the work, identity and culture of favela residents.

“We’re producing content for corporate media,” she said, pointing to examples of community media organizations and residents sharing information through Facebook, WhatsApp and other social media channels that mainstream media then uses for their own reporting. “This is the people’s technology, favelas have this technology.”

The difference, she said, is that community media organizations do this reporting to inform their audiences and help them navigate their daily lives, while mainstream media outlets use information on police operations or violence to continue stigmatizing and criminalizing favelas, portraying them as dangerous.

“We need to think about our practices, dialogue and empower ourselves as communicators,” she said, asking other community journalists to take pride in their work and their publications. “The space doesn’t just belong to corporate media, although they have a very strong presence. But I don’t think it should be closed, we can’t give up all the space to corporate media.”

She also cited a speech by Marcelo Rech, the president of Brazil’s National Association of Newspapers, in which he stated the role of journalists is to “verify the truth.”

“What is our role?” she asked. “What truth is it that they [mainstream reporters] verify? We verify our truth. The role of community media is to verify the truth that they leave out.”