Mapping Rio de Janeiro’s favelas can be a contentious political and social issue, and the debate has only amplified in the last few years, as Rio hosted increasingly high-profile global mega-events like the 2014 World Cup and this year’s Summer Olympics.

Google’s efforts to delete and then map favelas

In 2013, reportedly at the request of the city government and tourism companies, Google removed the word “favela,” and often any labels of the communities themselves, from its maps of Rio–communities which represent nearly one-quarter of Rio’s population. Searches yielded entirely wrong results or none at all, and the densely populated areas appeared on the map as beige-tinted blank spaces, or, at best, a series of empty outlines of squares that vaguely suggested houses.

The absence of favelas from the world’s most ubiquitous mapping tool has serious practical consequences–local businesses and street names do not appear in search results, making it even more challenging for anyone unfamiliar with the neighborhoods to access reliable directions–as well as less tangible, symbolic repercussions for residents.

“For me, the fact of not being on the map, creates a sense of exclusion. That we are not part of the city, that we are not part of the traditional script,” said Paulinho Otaviano, a resident and local guide in Santa Marta, in an interview in Todo Mapa Tem Um Discurso (Every Map Has a Discourse), a documentary that explores questions of mapping, geography, identity and representation in Rio’s favelas.

“It doesn’t make sense for us to be excluded from this reality,” he added.

The failure to map the favelas, however, long predates Google and 360-degree videos. For years, most favelas did not even appear on the official maps created by the Pereira Passos Institute (IPP), Rio’s city planning agency–despite the fact that these communities have been the focus of a number of new planning initiatives in the last decade.

The IPP only began to close some of the gaps in 2013, when, in conjunction with the defunct UPP Social program (and later the defunct Rio+Social program), it mapped 12 favelas, comprising 56 communities–a tiny percentage of the city’s thousand favela communities.

The changes to Google’s maps that same year, enacted before the World Cup brought tens of thousands of tourists to Rio, were reportedly the result of a campaign waged since 2009 by the mayor’s office and state tourism company Riotur to have the word “favela” removed from maps and replaced with “morro” (hill), or nothing at all. As a result, communities like Rocinha, Rio’s largest favela, and Favela Morro da Chacrinha in the West Zone, had the word dropped from their names, while others like Cantagalo in the South Zone became “Morro do Cantagalo.”

Some favelas are commonly known as morros or have the word in their name, but many residents saw the change as yet another way to minimize evidence of their presence in the city.

At the time, Rio’s Popular Committee for the World Cup and Olympics, which has organized campaigns calling attention to rights violations associated with mega-events in Rio, commented: “The virtual removal is part of a city project that tries to hide poverty and the poor as much in virtual environments as in reality, with forced removals.”

According to the team behind Todo Mapa Tem Um Discurso, the move to rename the favelas suggests that these areas contain nothing of interest or are simply uninhabited–even communities like Rocinha and Complexo da Maré, and others that are officially registered as neighborhoods, these two with well over 100,000 residents each.

In his interview in the documentary, community journalist and Rocinha resident Michel Silva explained:

“Rocinha has been considered a neighborhood since 1993, but when you look on Google, it doesn’t have a single street registered. Only the streets there at the entrance. It doesn’t have Laboriaux, or Caxopa street, which are traditional streets that everyone knows. Rocinha is internationally known and it doesn’t have anything on Google?”

Google has finally begun to respond to these criticisms and made some public steps toward remedying this deficit. In 2014, shortly after it removed the word “favela” from the maps, the tech giant began to work with AfroReggae, a local NGO, to map some of the very communities it had just deleted.

The Tá no Mapa (On the Map) project incorporated innovative techniques to map areas that are not accessible to vehicles, including sending out volunteers outfitted with high-tech recording backpacks known as Trekkers, rather than its usual periscope-wielding cars, to map the pedestrian-only favela streets. The mapping teams, often made up of residents, worked in conjunction with local chambers of commerce and neighborhood associations to document and register local businesses, streets, landmarks and points of interest.

According to Google, when it began the collaboration back in 2013, only .001% of Rio’s favelas appeared on official maps. As of July 2016, the teams had mapped 26 favelas and added more than 10,000 businesses to Google Maps, with a few more projected to be completed by the end of the year.

Just before the Olympics, Google’s Art and Culture project also rolled out Beyond the Map, an interactive multimedia mapping project created in collaboration with Epic Magazine, that offers viewers an immersive introduction to a few of Rio’s communities.

The narrator in the English introduction explains that many viewers may think of favelas as an “uncharted and mysterious spot on the map”–despite international recognition of some favelas, and the fact that their “uncharted” nature is, at least in part, a direct result of Google’s failure to add them to those very maps.

Visitors to Beyond the Map begin at the moto-taxi stand at the bottom of the hill in São Carlos, in central Rio. From there, viewers can choose their next step–a high-speed ride to the top of the hill on one of the moto-taxis, or following dizzying drone footage around the city to Complexo da Maré, Complexo do Alemão, Vidigal, Rocinha and the South Zone beaches.

In each of these locations, viewers can access video vignettes featuring residents like Paloma, an ambitious programming student in Maré; Luis, a teenage ballet dancer from Alemão; Morenas de Sol, an all-female drumming and performance group in Vidigal; Ricardo, the founder of Rocinha Surf School; and José Júnior, coordinator of AfroReggae.

In her interview, Paloma summarizes the feelings of exclusion that affect many favela residents. “The favela is a blank spot on the map,” she said. “It’s as if we didn’t exist.”

José Júnior outlined the broader goals of the project, which extend beyond simply labeling streets and adding businesses to the physical map. “Even though Rio de Janeiro has the largest population in these territories, they’re places that seem to be invisible,” he said. “This is a project of inclusion. It’s more than digital, it’s social.”

Not everyone views these projects so positively, though. Some residents have reportedly been resistant to the team’s efforts to photograph and map their homes or businesses, while others have suggested the primary motivation for Google and Microsoft’s favela-mapping initiatives comes from the potential for profit, rather than altruism. Nor is AfroReggae the only group organizing grassroots mapping efforts–residents of Maré have created their own neighborhood map, Vidigal has its own map for visitors, and others have contributed to open-source maps of favelas on Wikimapia.

As favelas begin to repopulate Google’s maps, though, these sectors still lag far behind other parts of the city in terms of representation and accuracy. The Google Street View images for the section of Maré close to Avenida Brasil, for example, date back to 2011–making them particularly outdated in the architecturally dynamic space of a favela. The images for the entrance to Providência are from 2012, and the entrance to Babilônia/Chapéu-Mangueira was documented in 2014, while there are no Street View images at all for Santa Marta or Vidigal, even despite these being two of the most popular favelas among tourists.

Even when there are Street View images, they rarely extend beyond a few blocks up the primary entrance road to the community. The one notable exception to these gaps is the relatively flat and grid-based (and car-accessible) City of God, which had its Street View images updated in February 2016, likely as part of the new mapping project.

Despite the progress on the collaborative mapping initiative in some communities, many favelas still lack names on Google’s maps–zoom in on Pavão-Pavãozinho in the South Zone, or Chacrinha in the West Zone, and viewers will see a few street names, but no name to tell them which community they’re looking at until they get close enough to catch the name of a school or the local Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) base.

Even the Pokemón Go craze has bypassed favela residents; because the game relies on Google Maps data to populate its world with tiny monsters, a lone Pokemón is a rare sight in most favelas.

Controversies with navigation app Waze

Google is hardly the only technology company falling short when it comes to mapping favelas. Waze, the navigation app popular with those new to town and Uber drivers, has been at the center of several recent controversies about its approach and safety features.

In March 2013, actors Tadeu Aguiar and Sérgio Menezes had their phones, sound equipment and car stolen after Waze directed them to take a detour through the Costa Barros favela of Complexo do Chapadão, in the North Zone. In December 2015, 70-year-old Regina Múrmura was killed when she and her husband Francisco followed their GPS into the Caramujo favela in Niterói, across the bay from Rio, where someone opened fire at their car, hitting the vehicle with 20 bullets. In an interview with CNN, Francisco Múrmura blamed Waze for the tragic mistake. “The app was responsible for everything. It was the Waze app who led us there. I have no doubt that they are responsible for it,” he said.

Rumblings of concern about security and GPS tools turned into an uproar after August 12, when reserve police officer Helio Andrade, from the distant state of Roraima, was shot and killed when he and another officer mistakenly entered Vila do João, in Maré.

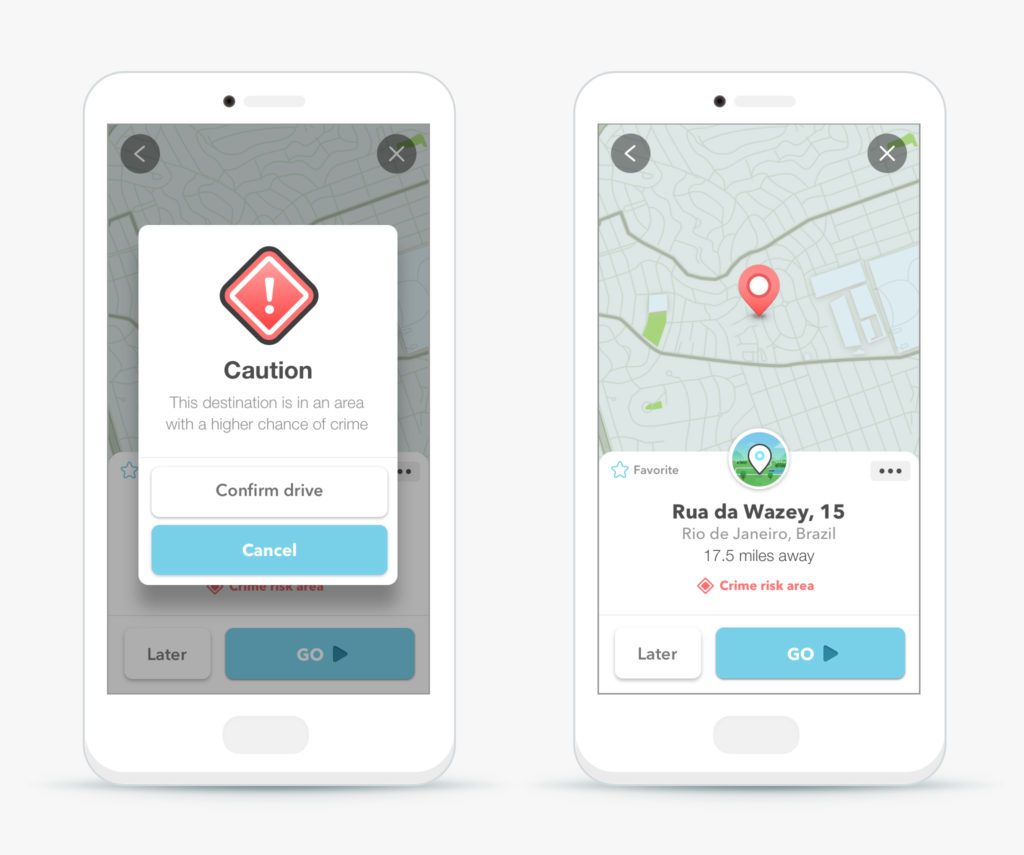

At the beginning of August, just before the Olympics began, Waze announced it was debuting a new safety feature called Crime Risk Alert, with a voice alert and bright red pop-up that would appear on the app when a driver entered one of 25 predetermined areas with “risk of crime.” According to Waze representatives, the update came in response to demand from its users, including those in Brazil, one of the app’s biggest markets and the only location in the world with this new feature.

The level of risk was based on data from public safety call center Disque Denúncia, and verified by volunteer map editors in Rio. The areas vary in size from one city block to whole neighborhoods, but do not include high-traffic areas, even if they also report high levels of crime.

Waze quickly faced criticism from some residents, who said the warnings would only reinforce stigma and negative perception of these areas. Representatives countered by saying Waze was intentionally not releasing the names of the “high-risk” neighborhoods or displaying them on a map to avoid appearing to criminalize them. Drivers only receive the alert if they enter an address in one of the areas as their destination, or enter a “risky” neighborhood with the app open on their device.

“We haven’t said you’re about to enter a… favela; we’re calling it an area with higher crime,” said Julie Mossler, head of brand and global marketing at Waze, in a statement. “Higher crime is data-driven. It’s not blanketly naming a neighborhood dangerous.”

Still, many residents remain unconvinced. In an article in community media outlet Viva Rocinha, one resident said, “When you map a part of the city and say that one part is dangerous and the other not, you are excluding people.” A Waze spokesperson told Quartz that Rocinha is not one of the 25 areas with alerts, though an article in the O Dia newspaper quoted sources stating that Rocinha was among the high-risk areas, along with communities like Alemão, Maré, Chapadão and Cajueiro.

Mapping and forecasting crime in Rio

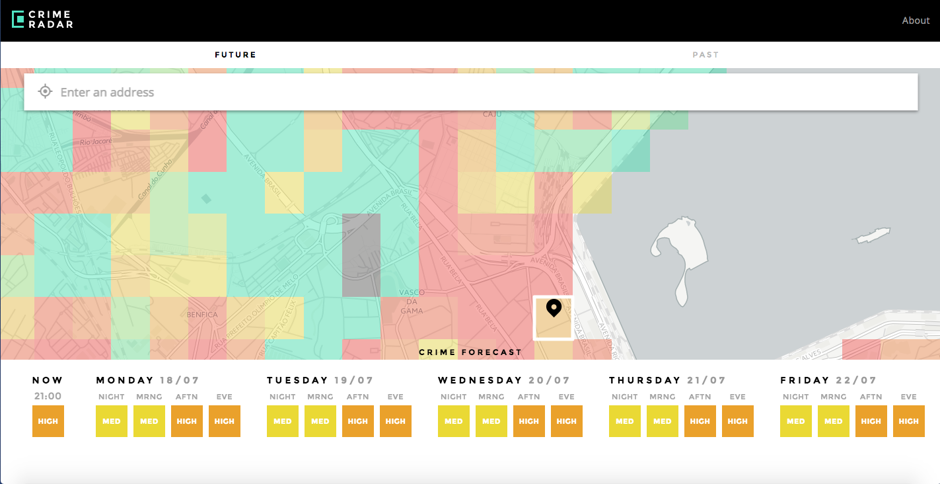

Near the end of August, the Igarapé Institute, a Rio-based security and policy think tank, unveiled its own mapping tool to track–and forecast–crime across the city.

CrimeRadar, touted as the world’s first public crime-forecasting tool based on open-access data, compiled data from 42 state police precincts, government entities and calls to Rio’s 190 emergency call system, on crimes committed between January 2010 and March 2016, totaling more than 14 million different crime events. The so-called “pre-crime” app also incorporates predictive analysis algorithms and tools to attempt to map future crime trends, essentially forecasting where crimes may be most likely to happen in the next week.

CrimeRadar, which runs on both desktops and smartphones, displays its predictive data as a color-coordinated heat map, where the potential risk in a given part of the city is coded on a scale of 1 to 10 and displayed with a corresponding color. Users can filter information based on the severity, category and frequency of different types of crimes, and view either historical records or predictions for the upcoming days, broken down by time of day.

The effort to increase citizen access to public safety information that is typically only available to law enforcement and government entities is admirable, but there are concerns about potentially contributing to stigmatization of certain communities.

CrimeRadar’s creators have stated that they considered these issues when designing the app. Rather than delineating neighborhoods as in the approach used by Waze, CrimeRadar displays the city in a uniform series of 250-square-meter zones, and does not include any profiling information about alleged perpetrators or victims of crimes.

In fact, Robert Muggah, a specialist in security and development and Research Director of Igarapé, says part of the aim of the app is to show residents and visitors to Rio that crime is not necessarily concentrated in favelas or low-income areas, and that risks may be greater in high-traffic tourist areas.

“We developed CrimeRadar to help trigger and drive a more data-driven and evidence-based debate on public security in Rio de Janeiro,” he told WIRED. “The idea is to create a reliable source of information rather than rely on episodic news reports which contribute to a sense of hysteria. Our goal is to make what are already publicly available statistics accessible and actionable for citizens.”

The source–and extent–of the data being used is a potential cause for concern. While Igarapé’s app uses the most complete set of available official information, many crimes in Rio go unreported, and police officers are known for tampering with crime scenes or mischaracterize crimes in their official reports, often to cover up human rights abuses. This unreliability of official data, and the simultaneous criminalization of certain neighborhoods and communities, is exactly what has given rise to citizen-driven apps like DefeZap and Nós por Nós which allow citizens to report incidents and violations by the police in their communities.

At the same time, many of the largest favelas are not yet included on CrimeRadar, including communities like Maré and Alemão which have suffered high levels of police violence and rights violations. According to the app’s creators, this omission is due to the lack of reliable official data–yet another way in which favelas are excluded from the “official” geography of Rio.

“The data gathered from these areas is often unreliable and subject to high levels of volatility,” explained Muggah.

“While we would like to fill in current data gaps–such as the favelas–our ability to do so depends on improvements to the quality of data collection and reporting,” Colin Gounden, CEO of Boston-based “big math” firm Via Science, which worked with Igarapé to develop the app’s predictive tools, told WIRED. He said there were currently no plans to incorporate crowd-sourced reporting on crime in these areas because of concerns about reliability of the resulting data.

Video game mapping

Ironically, the most widely-known maps of favelas may not even depict real favelas. For years, video game designers have coopted the image of favelas to create visually interesting environments for players, building on the stereotypes of favelas as violent, lawless and poorly constructed. This summer, designers of Rainbow Six Siege released a teaser introducing the game’s new favela map, marketed as the game’s “most destructible map to date.” A favela map was also featured in two releases of the popular Call of Duty game.

While these maps do not show actual favelas, and often perpetuate stigmatizing and negative stereotypes about favelas and their residents, they also feature more attention to detail than most official maps of favelas.

Still, the efforts of groups like AfroReggae and its Tá no Mapa initiative, as well as smaller mapping efforts at the local level like the youth-led Wikimapa project and a community-sourced print map of Vidigal that is updated annually, show that communities are organizing and stepping in to fill the gaps. This has helped them gain support from private-sector players like Google and Microsoft, though again, concerns remain about the business motives of these multinationals.

The issue of how to provide reliable, useful information to improve access, navigation and security for everyone is an ongoing challenge in a city as complex and dynamic as Rio, but simply erasing whole communities from the map is hardly a viable–or effective–solution, and it seems particularly targeted at Rio’s stigmatized favelas. After all, we haven’t seen Google deleting the sites of mass shootings in the US, terrorist attacks in Turkey or the repressive police crackdown in the Philippines–all areas with significant violence. On the other hand, the recent outcry over Google Maps’ approach to labeling Palestine suggests that the existence of political motives for why the search giant chooses to map certain areas is not exclusive to Rio.

The development of new apps like CrimeRadar and resources like Beyond the Map are important steps toward increasing public access to necessary data, but the limited scope of such technology and the dangerous potential for reinforcing negative stereotypes also show just how far there still is to go in the effort to put favelas on the map.